This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: March for Justice.

Introduction

What a contrast between this story and the one that concluded yesterday! In both stories there’s royal demands on parliaments for more money which led to rebellion. In this story from the Medieval Age the rebellion in England was crushed; in yesterday’s story from the Modern Age, the rebellion in France led to revolution and the King’s death.

This selection is from The History of England, From the First Invasion by the Romans to the Accession of Henry VIII by John Lingard published in 1819. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Father John Lingard was a revolutionary in another sense as he wrote a history of England during the very Protestant era of the 19th. century from the Catholic point of view.

Time: 1381

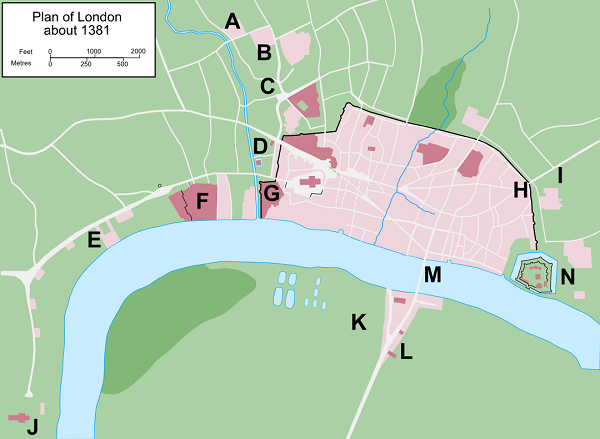

Place: Kent, England

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

At this period [1381 – jl] a secret ferment seems to have pervaded the mass of the people in many nations of Europe. Men were no longer willing to submit to the impositions of their rulers, or to wear the chains which had been thrown round the necks of their fathers by a warlike and haughty aristocracy. We may trace this awakening spirit of independence to a variety of causes, operating in the same direction; to the progressive improvement of society, the gradual diffusion of knowledge, the increasing pressure of taxation, and above all to the numerous and lasting wars by which Europe had lately been convulsed. Necessity had often compelled both the sovereigns and nobles to court the good-will of the people; the burghers in the towns and inferior tenants in the country had learned, from the repeated demands made upon them, to form notions of their own importance; and the archers and foot-soldiers, who had served for years in the wars, were, at their return home, unwilling to sit down in the humble station of bondmen to their former lords. In Flanders the commons had risen against their Count Louis, and had driven him out of his dominions; in France the populace had taken possession of Paris and Rouen, and massacred the collectors of the revenue. In England a spirit of discontent agitated the whole body of the villeins, who remained in almost the same situation in which we left them at the Norman Conquest. They were still attached to the soil, talliable at the will of the lord, and bound to pay the fines for the marriage of their females, to perform customary labor, and to render the other servile prestations incident to their condition. It is true that in the course of time many had obtained the rights of freemen. Occasionally the king or the lord would liberate at once all the bondmen on some particular domain, in return for a fixed rent to be yearly assessed on the inhabitants.

But the progress of emancipation was slow; the improved condition of their former fellows served only to embitter the discontent of those who still wore the fetters of servitude; and in many places the villeins formed associations for their mutual support, and availed themselves of every expedient in their power to free themselves from the control of their lords. In the first year of Richard’s reign a complaint was laid before parliament that in many districts they had purchased exemplifications out of the Domesday Book in the king’s court, and under a false interpretation of that record had pretended to be discharged of all manner of servitude both as to their bodies and their tenures, and would not suffer the officers of their lords either to levy distress or to do justice upon them. It was in vain that such exemplifications were declared of no force, and that commissions were ordered for the punishment of the rebellious. The villeins, by their union and perseverance, contrived to intimidate their lords, and set at defiance the severity of the law. To this resistance they were encouraged by the diffusion of the doctrines so recently taught by Wycliffe, that the right of property was founded in grace, and that no man, who was by sin a traitor to God, could be entitled to the services of others; at the same time itinerant preachers sedulously inculcated the natural equality of mankind, and the tyranny of artificial distinctions; and the poorer classes, still smarting under the exactions of the late reign, were by the impositions of the new tax wound up to a pitch of madness. Thus the materials had been prepared; it required but a spark to set the whole country in a blaze.

It was soon discovered that the receipts of the treasury would fall short of the expected amount; and commissions were issued to different persons to inquire into the conduct of the collectors, and to compel payment from those who had been favored or overlooked. One of these commissioners, Thomas de Bampton, sat at Brentwood in Essex; but the men of Fobbings refused to answer before him; and when the chief justice of the common pleas attempted to punish their contumacy, they compelled him to flee, murdered the jurors and clerks of the commission, and, carrying their heads upon poles, claimed the support of the nearest townships. In a few days all the commons of Essex were in a state of insurrection, under the command of a profligate priest, who had assumed the name of Jack Straw.

The men of Kent were not long behind their neighbors in Essex. At Dartford one of the collectors had demanded the tax for a young girl, the daughter of a tyler. Her mother maintained that she was under the age required by the statute; and the officer was proceeding to ascertain the fact by an indecent exposure of her person, when her father, who had just returned from work, with a stroke of his hammer beat out the offender’s brains. His courage was applauded by his neighbors. They swore that they would protect him from punishment, and by threats and promises secured the cooperation of all the villages in the western division of Kent.

A third party of insurgents was formed by the men of Gravesend, irritated at the conduct of Sir Simon Burley. He had claimed one of the burghers as his bondman, refused to grant him his freedom at a less price than three hundred pounds, and sent him a prisoner to the castle of Rochester. With the aid of a body of insurgents from Essex, the castle was taken and the captive liberated. At Maidstone they appointed Wat the tyler, of that town, leader of the commons of Kent, and took with them an itinerant preacher of the name of John Ball, who for his seditious and heterodox harangues had been confined by order of the archbishop. The mayor and aldermen of Canterbury were compelled to swear fidelity to the good cause; several of the citizens were slain; and five hundred joined them in their intended march toward London. When they reached Blackheath their numbers are said to have amounted to one hundred thousand men. To this lawless and tumultuous multitude Ball was appointed preacher, and assumed for the text of his first sermon the following lines:

“When Adam delved and Eve span,

Who was then the gentleman?”

He told them that by nature all men were born equal; that the distinction of bondage and freedom was the invention of their oppressors, and contrary to the views of their Creator; that God now offered them the means of recovering their liberty, and that, if they continued slaves, the blame must rest with themselves; that it was necessary to dispose of the archbishop, the earls and barons, the judges, lawyers, and questmongers; and that when the distinction of ranks was abolished, all would be free, because all would be of the same nobility and of equal authority. His discourse was received with shouts of applause by his infatuated hearers, who promised to make him, in defiance of his own doctrines, archbishop of Canterbury and chancellor of the realm.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.