The negligence of the public administration was betrayed, soon afterward, by a new disorder, which arose from the smallest beginnings.

Continuing Commodus’ Bad Reign,

our selection from The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon published in 1788. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Commodus’ Bad Reign.

Time: 180

Place: Rome

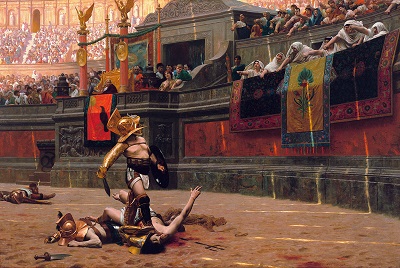

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Of these innocent victims of tyranny none died more lamented than the two brothers of the Quintilian family, Maximus and Condianus, whose fraternal love has saved their names from oblivion and endeared their memory to posterity. Their studies and their occupations, their pursuits and their pleasures, were still the same. In the enjoyment of a great estate they never admitted the idea of a separate interest: some fragments are now extant of a treatise which they composed in common; and in every action of life it was observed that their two bodies were animated by one soul. The Antonines, who valued their virtues and delighted in their union, raised them, in the same year, to the consulship; and Marcus afterward entrusted to their joint care the civil administration of Greece, and a great military command, in which they obtained a signal victory over the Germans. The kind cruelty of Commodus united them in death.

The tyrant’s rage, after having shed the noblest blood of the senate, at length recoiled on the principal instrument of his cruelty. While Commodus was immersed in blood and luxury, he devolved the detail of the public business on Perennis, a servile and ambitious minister, who had obtained his post by the murder of his predecessor, but who possessed a considerable share of vigor and ability. By acts of extortion and the forfeited estates of the nobles sacrificed to his avarice he had accumulated an immense treasure. The praetorian guards were under his immediate command; and his son, who already discovered a military genius, was at the head of the Illyrian legions. Perennis aspired to the empire; or what, in the eyes of Commodus, amounted to the same crime, he was capable of aspiring to it, had he not been prevented, surprised, and put to death.

The fall of a minister is a very trifling incident in the general history of the empire; but it was hastened by an extraordinary circumstance, which proved how much the nerves of discipline were already relaxed. The legions of Britain, discontented with the administration of Perennis, formed a deputation of fifteen hundred select men, with instructions to march to Rome and lay their complaints before the Emperor. These military petitioners, by their own determined behavior, by inflaming the divisions of the guards, by exaggerating the strength of the British army, and by alarming the fears of Commodus, exacted and obtained the minister’s death, as the only redress of their grievances. This presumption of a distant army, and their discovery of the weakness of government, were a sure presage of the most dreadful convulsions.

The negligence of the public administration was betrayed, soon afterward, by a new disorder, which arose from the smallest beginnings. A spirit of desertion began to prevail among the troops; and the deserters, instead of seeking their safety in flight or concealment, infested the highways. Maternus, a private soldier, of a daring boldness above his station, collected those bands of robbers into a little army, set open the prisons, invited the slaves to assert their freedom, and plundered with impunity the rich and defenseless cities of Gaul and Spain. The governors of the provinces, who had long been the spectators, and perhaps the partners, of his depredations, were at length roused from their supine indolence by the threatening commands of the Emperor. Maternus found that he was encompassed, and foresaw that he must be overpowered. A great effort of despair was his last resource. He ordered his followers to disperse, to pass the Alps in small parties and various disguises, and to assemble at Rome, during the licentious tumult of the festival of Cybele. To murder Commodus, and to ascend the vacant throne, were the ambition of no vulgar robber. His measures were so ably concerted that his concealed troops already filled the streets of Rome. The envy of an accomplice discovered and ruined this singular enterprise in the moment when it was ripe for execution.

Suspicious princes often promote the last of mankind from a vain persuasion that those who have no dependence, except on their favor, will have no attachment, except to the person of their benefactor. Cleander, the successor of Perennis, was a Phrygian by birth; of a nation over whose stubborn but servile temper blows only could prevail. He had been sent from his native country to Rome, in the capacity of a slave. As a slave he entered the imperial palace, rendered himself useful to his master’s passions, and rapidly ascended to the most exalted station which a subject could enjoy. His influence over the mind of Commodus was much greater than that of his predecessor; for Cleander was devoid of any ability or virtue which could inspire the Emperor with envy or distrust.

Avarice was the reigning passion of his soul and the great principle of his administration. The rank of consul, of patrician, of senator, was exposed to public sale; and it would have been considered as disaffection if anyone had refused to purchase these empty and disgraceful honors, with the greatest part of his fortune. In the lucrative provincial employments the minister shared with the governor the spoils of the people. The execution of the laws was venal and arbitrary. A wealthy criminal might obtain not only the reversal of the sentence by which he was justly condemned, but might likewise inflict whatever punishment he pleased on the accuser, the witnesses, and the judge.

By these means Cleander, in the space of three years, had accumulated more wealth than had ever yet been possessed by any freedman. Commodus was perfectly satisfied with the magnificent presents which the artful courtier laid at his feet in the most seasonable moments. To divert the public envy, Cleander, under the Emperor’s name, erected baths, porticoes, and places of exercise for the use of the people. He flattered himself that the Romans, dazzled and amused by this apparent liberality, would be less affected by the bloody scenes which were daily exhibited; that they would forget the death of Byrrhus, a senator to whose superior merit the late Emperor had granted one of his daughters; and that they would forgive the execution of Arrius Antoninus, the last representative of the name and virtues of the Antonines. The former, with more integrity than prudence, had attempted to disclose, to his brother-in-law, the true character of Cleander. An equitable sentence pronounced by the latter, when proconsul of Asia, against a worthless creature of the favorite proved fatal to him. After the fall of Perennis, the terrors of Commodus had for a short time assumed the appearance of a return to virtue. He repealed the most odious of his acts, loaded his memory with the public execration, and ascribed to the pernicious counsels of that wicked minister all the errors of his inexperienced youth. But his repentance lasted only thirty days; and, under Cleander’s tyranny, the administration of Perennis was often regretted.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.