Today’s installment concludes Commodus’ Bad Reign,

our selection from The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon published in 1788. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Commodus’ Bad Reign.

Time: 0180

Place: Rome

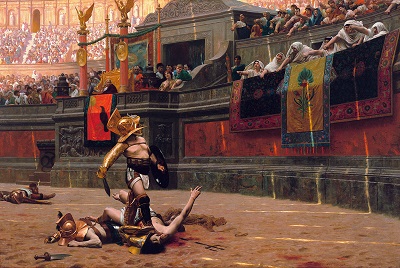

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

A panther was let loose, and the archer waited till he had leaped upon a trembling malefactor. In the same instant the shaft flew, the beast dropped dead, and the man remained unhurt. The dens of the Amphitheatre disgorged at once a hundred lions: a hundred darts from the unerring hand of Commodus laid them dead as they ran raging round the arena. Neither the huge bulk of the elephant nor the scaly hide of the rhinoceros could defend them from his stroke. Æthiopia and India yielded their most extraordinary productions; and several animals were slain in the Amphitheatre which had been seen only in the representations of art or perhaps of fancy. In all these exhibitions the securest precautions were used to protect the person of the Roman Hercules from the desperate spring of any savage, who might possibly disregard the dignity of the Emperor and the sanctity of the god.

But the meanest of the populace were affected with shame and indignation when they beheld their sovereign enter the lists as a gladiator, and glory in a profession which the laws and manners of the Romans had branded with the justest note of infamy.[*] He chose the habit and arms of the secutor, whose combat with the retiarius formed one of the most lively scenes in the bloody sports of the Amphitheatre. The secutor was armed with a helmet, sword, and buckler; his naked antagonist had only a large net and a trident; with the one he endeavored to entangle, with the other to despatch his enemy. If he missed the first throw, he was obliged to fly from the pursuit of the secutor till he had prepared his net for a second cast.

* The virtuous and even the wise princes forbade the senators and knights to embrace this scandalous profession, under pain of infamy, or, what was more dreaded by those profligate wretches, of exile. The tyrants allured them to dishonor by threats and rewards. Nero once produced in the arena forty senators and sixty knights.

The Emperor fought in this character seven hundred and thirty-five several times. These glorious achievements were carefully recorded in the public acts of the empire; and that he might omit no circumstance of infamy, he received from the common fund of gladiators a stipend so exorbitant that it became a new and most ignominious tax upon the Roman people. It may be easily supposed that in these engagements the master of the world was always successful; in the Amphitheatre his victories were not often sanguinary; but when he exercised his skill in the school of gladiators or his own palace, his wretched antagonists were frequently honored with a mortal wound from the hand of Commodus, and obliged to seal their flattery with their blood.

He now disdained the appellation of Hercules. The name of Paulus, a celebrated secutor, was the only one which delighted his ear. It was inscribed on his colossal statues and repeated in the redoubled acclamations of the mournful and applauding senate. Claudius Pompeianus, the virtuous husband of Lucilla, was the only senator who asserted the honor of his rank. As a father, he permitted his sons to consult their safety by attending the Amphitheatre. As a Roman he declared that his own life was in the Emperor’s hands, but that he would never behold the son of Marcus prostituting his person and dignity. Notwithstanding his manly resolution, Pompeianus escaped the resentment of the tyrant, and, with his honor, had the good fortune to preserve his life.

Commodus had now attained the summit of vice and infamy. Amid the acclamations of a flattering court he was unable to disguise from himself that he had deserved the contempt and hatred of every man of sense and virtue in his empire. His ferocious spirit was irritated by the consciousness of that hatred, by the envy of every kind of merit, by the just apprehension of danger, and by the habit of slaughter which he contracted in his daily amusements. History has preserved a long list of consular senators sacrificed to his wanton suspicion, which sought out, with peculiar anxiety, those unfortunate persons connected, however remotely, with the family of the Antonines, without sparing even the ministers of his crimes or pleasures.

His cruelty proved at last fatal to himself. He had shed with impunity the noblest blood of Rome: he perished as soon as he was dreaded by his own domestics. Marcia, his favorite concubine, Eclectus, his chamberlain, and Laetus, his praetorian prefect, alarmed by the fate of their companions and predecessors, resolved to prevent the destruction which every hour hung over their heads, either from the mad caprice of the tyrant or the sudden indignation of the people. Marcia seized the occasion of presenting a draught of wine to her lover, after he had fatigued himself with hunting some wild beasts. Commodus retired to sleep; but while he was laboring with the effects of poison and drunkenness, a robust youth, by profession a wrestler, entered his chamber and strangled him without resistance. The body was secretly conveyed out of the palace, before the least suspicion was entertained in the city, or even in the court, of the Emperor’s death. Such was the fate of the son of Marcus, and so easy was it to destroy a hated tyrant, who, by the artificial powers of government, had oppressed, during thirteen years, so many millions of subjects, each of whom was equal to their master in personal strength and personal abilities.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Commodus’ Bad Reign by Edward Gibbon from his book The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire published in 1788. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Commodus’ Bad Reign here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.