After a protracted passage of twelve weeks, the fleet arrived at Stadacona.

Continuing Cartier Explores Canada,

our selection from The History of Canada under French Regime by Henry H. Miles published in 1881. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Cartier Explores Canada.

Time: 1541

Place: Canadian Coast

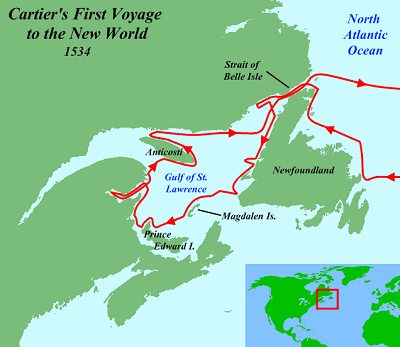

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Notwithstanding the apparent force of these objections, the French King did eventually sanction the project of another transatlantic enterprise on a larger scale than heretofore.

A sum of money was granted by the King toward the purchase and equipment of ships, to be placed under the command of Jacques Cartier, having the commission of captain-general.[1] Apart from the navigation of the fleet, the chief command in the undertaking was assigned to M. de Roberval, who, in a commission dated January 15, 1540, was named viceroy and lieutenant-general over Newfoundland, Labrador, and Canada. Roberval was empowered to engage volunteers and emigrants, and to supply the lack of these by means of prisoners to be taken from the jails and hulks. Thus, in about five years from the discovery of the river St. Lawrence, and, six years after, of Canada, measures were taken for founding a colony. But from the very commencement of the undertaking, which, it will be seen, proved an entire failure, difficulties presented themselves. Roberval was unable to provide all the requisite supplies of small arms, ammunition, and other stores, as he had engaged to do, during the winter of 1540. It also was found difficult to induce volunteers and emigrants to embark. It was, therefore, settled that Roberval should remain behind to complete his preparations, while Cartier, with five vessels, provisioned for two years, should set sail at once for the St. Lawrence.

[1] Commission dated October 20, 1540. In this document the French King’s appreciation of Cartier’s merits is strongly shown in the terms employed to express his royal confidence “in the character, judgment, ability, loyalty, dignity, hardihood, great diligence, and experience of the said Jacques Cartier.” Cartier was also authorized to select fifty prisoners “whom he might judge useful,” etc.

On May 23, 1541, Cartier departed from St. Malo on his third voyage to Canada. After a protracted passage of twelve weeks, the fleet arrived at Stadacona. Cartier and some of his people landed and entered into communication with the natives, who flocked round him as they had done in 1535. They desired to know what had become of their chief, Donacona, and the warriors who had been carried off to France five years before. On being made aware that all had died, they became distant and sullen in their behavior. They held out no inducements to the French to reestablish their quarters at Stadacona. Perceiving this, as well as signs of dissimulation, Cartier determined to take such steps as might secure himself and followers from suffering through their resentment. Two of his ships he sent back at once to France, with letters for the King and for Roberval, reporting his movements, and soliciting such supplies as were needed. With the remaining ships he ascended the St. Lawrence as far as Cap-Rouge, where a station was chosen close to the mouth of a stream which flowed into the great river. Here it was determined to moor the ships and to erect such storehouses and other works as might be necessary for security and convenience. It was also decided to raise a small fort or forts on the highland above, so as to command the station and protect themselves from any attack which the Indians might be disposed to make. While some of the people were employed upon the building of the fort, others were set at work preparing ground for cultivation. Cartier himself, in his report, bore ample testimony to the excellent qualities of the soil, as well as the general fitness of the country for settlement.[2]

[2] His description is substantially as follows: “On both sides of the river were very good lands filled with as beautiful and vigorous trees as are to be seen in the world, and of various sorts. A great many oaks, the finest I have ever seen in my life, and so full of acorns that they seemed like to break down with their weight. Besides these there were the most beautiful maples, cedars, birches, and other kinds of trees not to be seen in France. The forest land toward the south is covered with vines, which are found loaded with grapes as black as brambleberries. There were also many hawthorn-trees, with leaves as large as those of the oak, and fruit like that of the medlar-tree. In short, the country is as fit for cultivation as one could find or desire. We sowed seeds of cabbage, lettuce, turnips, and others of our country, which came up in eight days.”

Having made all the dispositions necessary for the security of the station at Cap-Rouge, and for continuing, during his absence, the works already commenced, Cartier departed for Hochelaga on September 7th, with a party of men, in two barges. On the passage up he found the Indians whom he had met in 1535 as friendly as before. The natives of Hochelaga seemed also well disposed, and rendered all the assistance he sought in enabling him to attempt the passage up the rapids situated above that town. Failing to accomplish this, he remained but a short time among them, gathering all the information they could furnish about the regions bordering on the Upper St. Lawrence. He then hastened back to Cap-Rouge. On his way down he found the Indians, who a short time before were so friendly, changed and cold in their demeanor, if not actually hostile. Arrived at Cap-Rouge, the first thing he learned was that the Indians had ceased to visit the station as at first, and, instead of coming daily with supplies of fish and fruit, that they only approached near enough to manifest, by their demeanor and gestures, feelings decidedly hostile toward the French. In fact, during Cartier’s absence, former causes of enmity had been heightened by a quarrel, in which, although some of his own people had, in the first instance, been the aggressors, a powerful savage had killed a Frenchman, and threatened to deal with another in like manner.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.