This series has seven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Cartier’s First Voyage Begins.

Introduction

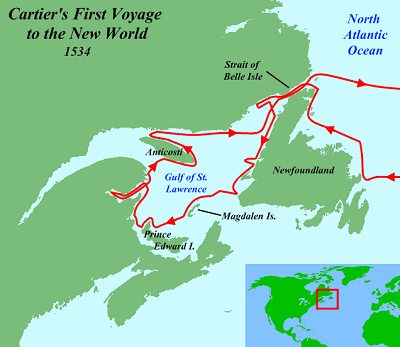

On April 20, 1534, Cartier, with two small vessels of about sixty tons each, set sail from the Britanny port of St. Malo for Newfoundland, on the banks of which Cartier’s Breton and Norman countrymen had long been accustomed to fish. The incidents of this and the subsequent voyages of the St. Malo mariner, with an account of the expedition under the Viceroy of Canada, the Sieur de Roberval, will be found appended in Dr. Miles’ interesting narrative.

This selection is from The History of Canada under French Regime by Henry H. Miles published in 1881. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Time: 1534

Place: Canadian Coast

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Canada was discovered in the year 1534, by Jacques Cartier (or Quartier), a mariner belonging to the small French seaport St. Malo. He was a man in whom were combined the qualities of prudence, industry, skill, perseverance, courage, and a deep sense of religion. Commissioned by the King of France, Francis I, he conducted three successive expeditions across the Atlantic for the purpose of prosecuting discovery in the western hemisphere; and it is well understood that he had previously gained experience in seamanship on board fishing-vessels trading between Europe and the Banks of Newfoundland.

He was selected and recommended to the King for appointment as one who might be expected to realize, for the benefit of France, some of the discoveries of his predecessor, Verrazano, which had been attended with no substantial result, since this navigator and his companions had scarcely done more than view, from a distance, the coasts of the extensive regions to which the name of New France had been given. It was also expected of Cartier that, through his endeavors, valuable lands would be taken possession of in the King’s name, and that places suitable for settlement, and stations for carrying on traffic, would be established. Moreover, it was hoped that the precious metals would be procured in those parts, and that a passage onward to China (Cathay) and the East Indies would be found out. And, finally, the ambitious sovereign of France was induced to believe that, in spite of the pretensions of Portugal and Spain,[1] he might make good his own claim to a share in transatlantic territories.

[1] The courts of Spain and Portugal had protested against any fresh expedition from France to the west, alleging that, by right of prior discovery, as well as the Pope’s grant of all the western regions to themselves, the French could not go there without invading their privileges. Francis, on the other hand, treated these pretensions with derision, observing sarcastically that he would “like to see the clause in old Father Adam’s will by which an inheritance so vast was bequeathed to his brothers of Spain and Portugal.”

With such objects in view, Jacques Cartier set sail from St. Malo, on Monday, April 20, 1534.[2] His command consisted of two small vessels, with crews amounting to about one hundred twenty men, and provisioned for four or five months.

[2] The dates in this and subsequent pages are in accordance with the “old style” of reckoning.

On May 10th the little squadron arrived off Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland; but, as the ice and snow of the previous winter had not yet disappeared, the vessels were laid up for ten days in a harbor near by, named St. Catherine’s. From this, on the 21st, they sailed northward to an island northeast of Cape Bonavista, situated about forty miles from the mainland, which had been called by the Portuguese the “Isle of Birds.” Here were found several species of birds which, it appears, frequented the island at that season of the year in prodigious numbers, so that, according to Cartier’s own narrative, the crews had no difficulty in capturing enough of them, both for their immediate use and to fill eight or ten large barrels (pippes) for future consumption. Bears and foxes are described as passing from the mainland, in order to feed upon the birds as well as their eggs and young.

From the Isle of Birds the ships proceeded northward and westward until they came to the Straits of Belle-Isle, when they were detained by foul weather, and by ice, in a harbor, from May 27th until June 9th. The ensuing fifteen days were spent in exploring the coast of Labrador as far as Blanc Sablon and the western coast of Newfoundland. For the most part these regions, including contiguous islands, were pronounced by Cartier to be unfit for settlement, especially Labrador, of which he remarks, “it might, as well as not, be taken for the country assigned by God to Cain.” From the shore of Newfoundland the vessels were steered westward across the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and about June 25th arrived in the vicinity of the Magdalen Islands. Of an island named “Isle Bryon,” Cartier says it contained the best land they had yet seen, and that “one acre of it was worth the whole of Newfoundland.” Birds were plentiful, and on its shores were to be seen “beasts as large as oxen and possessing great tusks like elephants, which, when approached, leaped suddenly into the sea.” There were very fine trees and rich tracts of ground, on which were seen growing quantities of “wild corn, peas in flower, currants, strawberries, roses, and sweet herbs.” Cartier noticed the character of the tides and waves, which swept high and strong among the islands, and which suggested to his mind the existence of an opening between the south of Newfoundland and Cape Breton.

Toward the end of June the islands and mainland of the northwest part of the territory now called New Brunswick came in sight, and, as land was approached, Cartier began at once to search for a passage through which he might sail farther westward.

The ships’ boats were several times lowered, and the crews made to row close inshore in the bays and inlets, for the purpose of discovering an opening. On these occasions natives were sometimes seen upon the beach, or moving about in bark canoes, with whom the French contrived to establish a friendly intercourse and traffic, by means of signs and presents of hatchets, knives, small crucifixes, beads, and toys. On one occasion they had in sight from forty to fifty canoes full of savages, of which seven paddled close up to the French boats, so as to surround them, and were driven away only by demonstrations of force. Cartier learned afterward that it was customary for these savages to come down from parts more inland, in great numbers, to the coast, during the fishing season, and that this was the cause of his finding so many of them at that time. On the 7th day of the month a considerable body of the same savages came about the ships, and some traffic occurred. Gifts, consisting of knives, hatchets, and toys, along with a red cap for their head chief, caused them to depart in great joy.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.