France was now engaged in a foreign war; and at the same time the minds of the people were distracted by religious dissensions.

Continuing Cartier Explores Canada,

our selection from The History of Canada under French Regime by Henry H. Miles published in 1881. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Cartier Explores Canada.

Time: 1536

Place: Canadian Coast

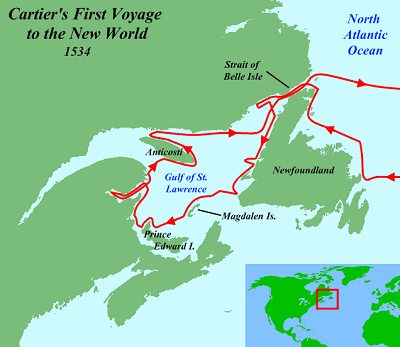

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

One of the ships had to be abandoned in course of the winter, her crew and contents being removed into the other two vessels. The deserted hull was visited by the savages in search of pieces of iron and other things. Had they known the cause for abandoning her, and the desperate condition of the French, they would have soon forced their way into the other ships. They were, in fact, too numerous to be resisted if they had made the attempt.

At length the protracted winter came to an end. As soon as the ships were clear of ice, Cartier made preparations for returning at once to France.

On May 3, 1536, a wooden cross, thirty-five feet high, was raised upon the river bank. Donacona was invited to approach, along with his people. When he did so, Cartier caused him, together with the two interpreters and seven warriors, to be seized and taken on board his ship. His object was to convey them to France and present them to the King. On the 6th, the two vessels departed. Upward of six weeks were spent in descending the St. Lawrence and traversing the gulf. Instead of passing through the Straits of Belle-Isle, Cartier this time made for the south coast of Newfoundland, along which he sailed out into the Atlantic Ocean. On Sunday, July 17, 1536, he arrived at St. Malo.

By the results of this second voyage, Jacques Cartier established for himself a reputation and a name in history which will never cease to be remembered with respect. He had discovered one of the largest rivers in the world, had explored its banks, and navigated its difficult channel more than eight hundred miles, with a degree of skill and courage which has never been surpassed; for it was a great matter in those days to penetrate so far into unknown regions, to encounter the hazards of an unknown navigation, and to risk his own safety and that of his followers among an unknown people. Moreover, his accounts of the incidents of his sojourn of eight months, and of the features of the country, as well as his estimate of the two principal sites upon which, in after times, the two cities, Quebec and Montreal, have grown up, illustrate both his fidelity and his sagacity. His dealings with the natives appear to have been such as to prove his tact, prudence, and sense of justice, notwithstanding the objectionable procedure of capturing and carrying off Donacona with other chiefs and warriors. This latter measure, however indefensible in itself, was consistent with the almost universal practice of navigators of that period and long afterward. Doubtless Cartier’s expectation was that their abduction could not but result in their own benefit by leading to their instruction in civilization and Christianity, and that it might be afterward instrumental in producing the rapid conversion of large numbers of their people. However this may be, considering the inherent viciousness of the Indian character, Cartier’s intercourse with the Indians was conducted with dignity and benevolence, and was marked by the total absence of bloodshed — which is more than can be urged in behalf of other eminent discoverers and navigators of those days or during the ensuing two centuries. Cartier was undoubtedly one of the greatest sea-captains of his own or any other country, and one who provided carefully for the safety and welfare of his followers, and, so far as we know, enjoyed their respect and confidence; nor were his plans hindered or his proceedings embarrassed by disobedience on their part or the display of mutinous conduct calculated to mar the success of a maritime expedition. In fine, Jacques Cartier was a noble specimen of a mariner, in an age when a maritime spirit prevailed.

A severe disappointment awaited Cartier on his return home from his second voyage. France was now engaged in a foreign war; and at the same time the minds of the people were distracted by religious dissensions. In consequence of these untoward circumstances, both the court and the people had ceased to give heed to the objects which he had been so faithfully engaged in prosecuting in the western hemisphere. Neither he nor his friends could obtain even a hearing in behalf of the fitting out of another expedition, for the attention of the King and his advisers was now absorbed by weightier cares at home. Nevertheless, from time to time, as occasion offered, several unsuccessful attempts were made to introduce the project of establishing a French colony on the banks of the St. Lawrence. Meanwhile, Donacona, and the other Indian warriors who had been brought captives to France, pined away and died.

At length, after an interval of about four years, proposals for another voyage westward, and for colonizing the country, came to be so far entertained that plans of an expedition were permitted to be discussed. But now, instead of receiving the unanimous support which had been accorded to previous undertakings, the project was opposed by a powerful party at court, consisting of persons who tried to dissuade the King from granting his assent. These alleged that enough had already been done for the honor of their country; that it was not expedient to take in hand the subjugation and settlement of those far-distant regions, tenanted only by savages and wild animals; that the intensely severe climate and hardships such as had proved fatal to one-fourth of Cartier’s people in 1535, were certain evils, which there was no prospect of advantage to outweigh; that the newly discovered country had not been shown to possess mines of gold and silver; and, finally, that such extensive territories could not be effectively settled without transporting thither a considerable part of the population of the kingdom of France.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.