Natives were very poor and anxious to trade with these new-comers.

Continuing Cartier Explores Canada,

our selection from The History of Canada under French Regime by Henry H. Miles published in 1881. The selection is presented in seven» easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Cartier Explores Canada.

Time: 1534

Place: Canadian Coast

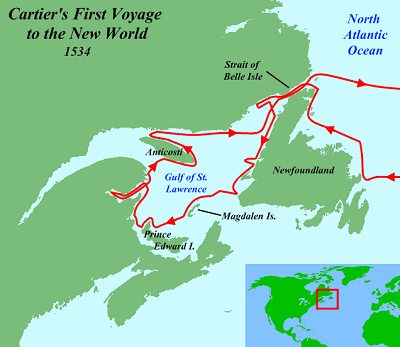

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Early in July, Cartier found that he was in a considerable bay, which he named “La Baie des Chaleurs.” He continued to employ his boats in the examination of the smaller inlets and mouths of the rivers flowing into the bay, hoping that an opening might be discovered similar to that by which, a month before, he had passed round the north of Newfoundland into the gulf. After the 16th the weather was boisterous, and the ships were anchored for shelter close to the shore several days. During this time the savages came there to fish for mackerel, which were abundant, and held friendly intercourse with Cartier and his people. They were very poor and miserably clad in old skins, and sang and danced to testify their pleasure on receiving the presents which the French distributed among them.

Sailing eastward and northward, the vessels next passed along the coast of Gaspe, upon which the French landed and held intercourse with the natives. Cartier resolved to take formal possession of the country, and to indicate, in a conspicuous manner, that he did so in the name of the King, his master, and in the interests of religion. With these objects in view, on Friday, July 24th, a huge wooden cross, thirty feet in height, was constructed, and was raised with much ceremony, in sight of many of the Indians, close to the entrance of the harbor; three fleurs-de-lys being carved under the cross, and an inscription, “Vive le Roy de France.” The French formed a circle on their knees around it, and made signs to attract the attention of the savages, pointing up to the heavens, “as if to show that by the cross came their redemption.” These ceremonies being ended, Cartier and his people went on board, followed from the shore by many of the Indians. Among these the principal chief, with his brother and three sons, in one canoe, came near Cartier’s ship. He made an oration, in course of which he pointed toward the high cross, and then to the surrounding territory, as much as to say that it all belonged to him, and that the French ought not to have planted it there without his permission. The sight of hatchets and knives displayed before him, in such a manner as to show a desire to trade with him, made him approach nearer, and, at the same time, several sailors, entering his canoe, easily induced him and his companions to pass into the ship. Cartier, by signs, endeavored to persuade the chief that the cross had been erected as a beacon to mark the way into the harbor; that he would revisit the place and bring hatchets, knives, and other things made of iron, and that he desired the friendship of his people. Food and drink were offered, of which they partook freely, when Cartier made known to the chief his wish to take two of his sons away with him for a time. The chief and his sons appear to have readily assented. The young men at once put on colored garments, supplied by Cartier, throwing out their old clothing to others near the ship. The chief, with his brother and remaining son, were then dismissed with presents. About midday, however, just as the ships were about to move farther from shore, six canoes, full of Indians, came to them, bringing presents of fish, and to enable the friends of the chief’s sons to bid them adieu. Cartier took occasion to enjoin upon the savages the necessity of guarding the cross which had been erected, upon which the Indians replied in unintelligible language. Next day, July 25th, the vessels left the harbor with a fair wind, making sail northward to 50° latitude. It was intended to prosecute the voyage farther westward, if possible; but adverse winds, and the appearance of the distant headlands, discouraged Cartier’s hopes so much that on Wednesday, August 5th, after taking counsel with his officers and pilots, he decided that it was not safe to attempt more that season. The little squadron, therefore, bore off toward the east and northeast, and made Blanc Sablon on the 9th. Continuing thence their passage into the Atlantic, they were favored with fair winds, which carried them to the middle of the ocean, between Newfoundland and Bretagne. They then encountered storms and adverse winds, respecting which Cartier piously remarks: “We suffered and endured these with the aid of God, and after that we had good weather and arrived at the harbor of St. Malo, whence we had set out, on September 5, 1534.” Thus ended Jacques Cartier’s first voyage to Canada. As a French-Canadian historian of Canada has observed, this first expedition was not “sterile in results”; for, in addition to the other notable incidents of the voyage, the two natives whom he carried with him to France are understood to have been the first to inform him of the existence of the great river St. Lawrence, which he was destined to discover the following year.

It is not certainly known how nearly he advanced to the mouth of that river on his passage from Gaspe Bay. But it is believed that he passed round the western point of Anticosti, subsequently named by him Isle de l’Assumption, and that he then turned to the east, leaving behind the entrance into the great river, which he then supposed to be an extensive bay, and, coasting along the shore of Labrador, came to the river Natachquoin, near Mount Joli, whence, as already stated, he passed eastward and northward to Blanc Sablon.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.