Pius IX was hardly more fortunate; to him also this fatal war brought dishonor and exile, the loss of the affection of his subjects, and of the admiration of the civilized world.

Continuing Pius IX Flees Rome,

our selection from Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) by Francis Bowen published in 1852. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Pius IX Flees Rome.

Time: 1848

Place: Rome

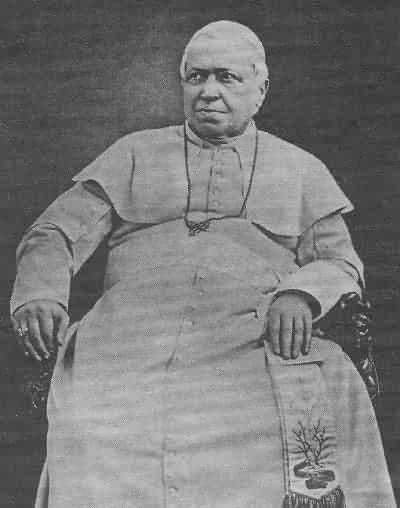

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But what prevented the people themselves from crowding the camp of Charles Albert with volunteers at a time when not a crowned head in Italy dared offer the least open opposition to such a movement? The King of Naples, sorely against his will, sent his regular army, consisting of about fourteen thousand men, to fight for the cause, and withdrew them in about six weeks, as soon as a base act of treachery had given him the victory at home. General Pepe, their commander, wished to disobey the order and move forward; but “nearly the whole army turned its back on the Po and on him, and moved backward in the direction of the Neapolitan Kingdom.” Two hundred volunteers had previously set out from Naples for Upper Italy, under the guidance and at the expense of an enthusiastic woman, the Princess Belgioioso. “She had lived as an exile in France, and was at first enthusiastic for the Giovine Italia; she afterward became averse to it, and sided with Guizot, Duchâtel, and Mignet, her intimate friend. She was well versed — or mixed herself much — in literature, politics, the study of theology, and journalism; a woman that had some of the feelings and anxieties of men, together with all those of her own sex, and who was now traveling through Italy intent upon manly business, but after woman’s fashion. Other volunteers afterward started, and a vessel set sail for Leghorn, which carried them, along with the Tenth Regiment of the line.” The Sicilians at the same time determined to separate entirely from Naples and the rest of the peninsula; “and thus all the ability and spirit, the arms and wealth, of that powerful island were applied to the effort for insular independence, and drawn off from that for the independence of the nation.” From Tuscany there went to this national war “about three thousand volunteers, and perhaps as many more regulars” — a number so small that Farini apologizes for it, and endeavors to prove that it ought “not to be imputed to any lukewarmness in the affection for Italy.” The army from the Roman States, which the Pope had set on foot, but hoped to retain as a defensive force within the northern boundary of his dominions, numbered about sixteen thousand, of whom more than half were volunteers. The conduct of the people of Lombardy, who though the conflict raged on their own soil, and their own freedom was immediately at stake, wasted their strength in quarrelling with one another instead of succoring Charles Albert, has long been a topic of wonder and censure. In short, all Italy did not furnish for this sacred war, so long the object of her aspirations and her prayers, a body of volunteers one-fourth as large as the army which the King of Sardinia brought into the field, though it was probable that he was moved from the first only by the hope of personal aggrandizement. He invaded Lombardy with an army of fifty-five thousand men, expecting thereby to win, with the aid of the national enthusiasm, the scepter of all Italy for himself and his descendants. A terrible disappointment awaited him; instead of glory, shame and defeat were his portion; and having abdicated his paternal throne in despair he died in exile, literally of a broken heart. Pius IX was hardly more fortunate; to him also this fatal war brought dishonor and exile, the loss of the affection of his subjects, and of the admiration of the civilized world. The reluctance of the Pope to engage, when unprovoked, in a war with Austria is no cause for wonder. He earnestly desired the welfare of his people and the independence of his native land; but all his desires were subject to the interests of the Church, of which he was the recognized head throughout Christendom. The republicans in his dominions, including Mazzini and his party, were aware of this reluctance, and determined to make use of it and of the passions of the people in order to get rid of him altogether. No opportunity was lost to compromise him in the war, both in his temporal and ecclesiastical character; and the misfortune of his twofold position did not allow him to resist these machinations with success. General Durando, the commander of the papal forces, issued a flaming proclamation to his army when they passed the Po, announcing to them that their swords were blessed by the venerable head of the Church, and that they should all wear the cross on their bosoms, as beseemed those who were engaged in a holy war. This act naturally gave great uneasiness to the Pope, and Farini censures it as an unwise attempt to obtain the sanctions of religion for merely political objects — the very conduct which the Liberal party had previously censured in their opponents. If Italian minds, he argues, “were not capable of warming with the simple fire of patriotism for the noble and even holy enterprise of liberating Italy from the stranger, it was vain to hope that hearts so frozen up in indifference could kindle with religious faith.” In the mean time the Germans, who were speculating about the unity of their own stock and nation and were straining every nerve in that difficult enterprise, could not excuse the desire of independence in the Italians, and contended for the boasted rights of Austria and Germany over the lands and the coasts of Italy, with the people that inhabited them. When it became known in Germany that the pontifical troops were hastening to the legitimate defense of Italy it affected the public feeling generally, and the name of Pius IX was branded with censure, not by laymen only, but by some bishops and high ecclesiastics. Monsignor Viale, nuncio at Vienna, and Monsignor Sacconi, nuncio at Munich, were assiduous and eager in detailing the sinister reports touching Rome and the Pope, and colored them in such a way as to create an apprehension of schism, the most serious one that could rise for a pope — and that pope, too, Pius IX.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.