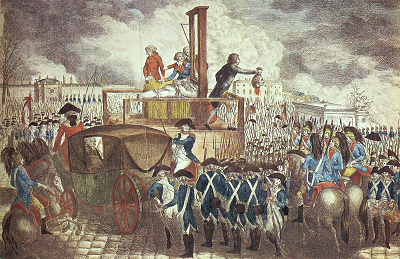

His hands are tied, his head bare; the fatal moment is come.

Continuing Murders of Louis XVI and Murat; Civil War in France,

our selection from The French Revolution — A History by Thomas Carlyle published in 1837. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Murders of Louis XVI and Murat; Civil War in France.

Time: 1793

Place: France

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At the Temple Gate were some faint cries, perhaps from voices of pitiful women: “Grace! Grace!” Through the rest of the streets there is silence as of the grave. No man not armed is allowed to be there: the armed, did any even pity, dare not express it, each man overawed by all his neighbors. All windows are down, none seen looking through them. All shops are shut. No wheel-carriage rolls, this morning, in these streets but one only. Eighty thousand armed men stand ranked, like armed statues of men; cannons bristle, cannoneers with match burning, but no word or movement: it is as a city enchanted into silence and stone: one carriage with its escort, slowly rumbling, is the only sound. Louis reads, in his Book of Devotion, the Prayers of the Dying: clatter of this death-march falls sharp on the ear, in the great silence; but the thought would fain struggle heavenward, and forget the Earth.

As the clocks strike ten, behold the Place de la Revolution, once Place de Louis Quinze: the Guillotine, mounted near the old Pedestal where once stood the Statue of that Louis! Far round, all bristles with cannons and armed men: spectators crowding in the rear; D’Orleans Egalite there in cabriolet. Swift messengers, hoquetons, speed to the Town-hall every three minutes: near by is the Convention sitting — vengeful for Lepelletier. Heedless of all, Louis reads his Prayers of the Dying; not till five minutes yet has he finished; then the Carriage opens. What temper he is in? Ten different witnesses will give ten different accounts of it. He is in the collision of all tempers; arrived now at the black Maelstrom and descent of Death: in sorrow, in indignation, in resignation struggling to be resigned. “Take care of M. Edgeworth,” he straitly charges the Lieutenant who is sitting with them: then they two descend.

The drums are beating: “Taisez-vous!” (“Silence!”) he cries “in a terrible voice” (d’une voix terrible). He mounts the scaffold, not without delay; he is in puce coat, breeches of gray, white stockings. He strips off the coat; stands disclosed in a sleeve-waistcoat of white flannel. The Executioners approach to bind him: he spurns, resists; Abbe Edgeworth has to remind him how the Saviour, in whom men trust, submitted to be bound. His hands are tied, his head bare; the fatal moment is come. He advances to the edge of the Scaffold, “his face very red,” and says: “Frenchmen, I die innocent: it is from the Scaffold and near appearing before God that I tell you so. I pardon my enemies; I desire that France — — ” A General on horseback, Santerre or another, prances out, with uplifted hand: “Tambours!” The drums drown the voice. “Executioners, do your duty!” The Executioners, desperate lest themselves be murdered (for Santerre and his Armed Ranks will strike, if they do not), seize the hapless Louis: six of them desperate, him singly desperate, struggling there; and bind him to their plank. Abbe Edgeworth, stooping, bespeaks him: “Son of Saint Louis, ascend to Heaven.” The Axe clanks down; a King’s Life is shorn away. It is Monday, January 21, 1793. He was aged thirty-eight years four months and twenty-eight days.

Executioner Samson shows the Head: fierce shout of “Vive la Republique” rises, and swells; caps raised on bayonets, hats waving: students of the College of Four Nations take it up, on the far Quais; fling it over Paris. D’Orleans drives off in his cabriolet: the Town-hall Councillors rub their hands, saying, “It is done, It is done.” There is dipping of handkerchiefs, of pike-points in the blood. Headsman Samson, though he afterward denied it, sells locks of the hair: fractions of the puce coat are long after worn in rings. — And so, in some half-hour it is done and the multitude has all departed. Pastry-cooks, coffee-sellers, milkmen sing out their trivial quotidian cries: the world wags on, as if this were a common day. In the coffee-houses that evening, says Prudhomme, Patriot shook hands with Patriot in a more cordial manner than usual. Not till some days after, according to Mercier, did public men see what a grave thing it was.

In the leafy months of June and July, several French Departments germinate a set of rebellious paper-leaves, named Proclamations, Resolutions, Journals, or Diurnals, “of the Union for Resistance to Oppression.” In particular, the Town of Caen, in Calvados, sees its paper-leaf of Bulletin de Caen suddenly bud, suddenly establish itself as Newspaper there; under the Editorship of Girondin National Representatives!

For among the proscribed Girondins are certain of a more desperate humor. Some, as Vergniaud, Valaze, Gensonne “arrested in their own houses,” will await with stoical resignation what the issue may be. Some, as Brissot, Rabaut, will take to flight, to concealment; which, as the Paris Barriers are opened again in a day or two, is not yet difficult. But others there are who will rush, with Buzot, to Calvados; or far over France, to Lyons, Toulon, Nantes and elsewhither, and then rendezvous at Caen: to awaken as with war-trumpet the respectable Departments; and strike down an anarchic “Mountain” Faction; at least not yield without a stroke at it. Of this latter temper we count some score or more, of the Arrested, and of the Not-yet-arrested: a Buzot, a Barbaroux, Louvet, Guadet, Petion, who have escaped from Arrestment in their own homes; a Salles, a Pythagorean Valady, a Duchatel, the Duchatel that came in blanket and nightcap to vote for the life of Louis, who have escaped from danger and likelihood of Arrestment. These, to the number at one time of Twenty-seven, do accordingly lodge here, at the “Intendance, or Departmental Mansion,” of the town of Caen in Calvados; welcomed by Persons in Authority; welcomed and defrayed, having no money of their own. And the Bulletin de Caen comes forth, with the most animating paragraphs: How the Bordeaux Department, the Lyons Department, this Department after the other is declaring itself; sixty, or say sixty-nine, or seventy-two respectable Departments either declaring, or ready to declare. Nay Marseilles, it seems, will march on Paris by itself, if need be. So has Marseilles Town said, That she will march. But on the other hand, that Montelimart Town has said, No thoroughfare; and means even to “bury herself” under her own stone and mortar first — of this be no mention in Bulletin de Caen.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.