This series has eleven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Pope Pius IX’s Early Reforms.

Introduction

In the long roll of pontiffs the name of Pius IX stands conspicuous among those of popes, who have greatly exerted their power for effect upon the papacy itself. But the influence of Pius IX was not less marked in Italian and European politics. An account of the reforms which he undertook and of the obstacles he had to confront, cannot fail to convey, directly or by implication, matters of much importance in modern history. That a pope who signalized the beginning of his official career by a series of liberal reforms should soon have been driven from his see by revolutionists is one of the historical paradoxes for which even the “philosophy of history” finds it difficult to account. But, as one writer tells us, “The revolutionary fever of 1848 spread too fast for a reforming pope, and his refusal to make war upon the Austrians finally cost him the affections of the Romans.”

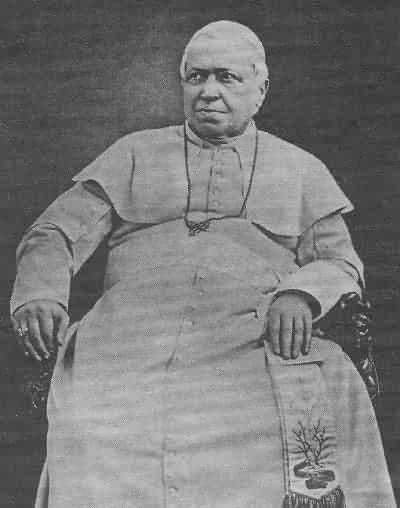

Pope Pius IX (Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti) who at the age of fifty-four brought the power of his papal throne to advance the cause of Young Italy — led by Mazzini and other patriots — was born at Sinigaglia May 13, 1792. He was descended from a noble family, and his early education was received at the College of Volterra. Throughout the years of his youth he suffered from infirm health, but before reaching thirty he gained much in strength, and in 1827 became Archbishop of Spoleto. In 1840 he was made cardinal by Pope Gregory XVI. Gregory died June 1, 1846, and after being two days in conclave the cardinals elected their colleague Ferretti to succeed him. The cardinals felt the advisability of choosing for pope a native of the Papal States, a man not too far advanced in years, and one “who would see the necessity of correcting abuses and making some reforms.”

This selection is from Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) by Francis Bowen published in 1852.

Francis Bowen, whose review of Pope Pius’s career, from his entrance upon the papal office until his temporary withdrawal from Rome, is here presented, is a well-known authority in this as also in other fields of history, and his recital is based upon the best contemporary accounts.

Time: 1848

Place: Rome

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

When Pius IX was elected Pope his course did not long remain doubtful. He limited the expenses of the court at once, dispensed alms in abundance, set aside one day of each week for giving audiences, and commanded that political inquisitions should be stopped immediately. These few steps, taken before he had had time to consult with others, afford perhaps a better indication of the mild and kind character of the new pontiff than the grave political acts which were subsequently performed. These show us the man, the others reveal only the sovereign. Just one month after his election, a manifesto of amnesty for all political offenders was published at Rome, including the exiles, those awaiting trial, and those undergoing sentence. The only conditions imposed were that the individuals pardoned should give their word of honor never to abuse the indulgence, and would fulfill every duty of a good citizen.

The news of this act flew like the wind through the Papal States, and caused everywhere a burst of exultation and gratitude toward the new sovereign. It carried joy to thousands of households, bringing back to them the long-separated brother or parent, and it was a token of future peace and contentment. In the city, says Farini,* the hosannas were countless; each citizen embraced his neighbor like a brother; thousands of torches blazed in the evening; the multitude ran to the palace of the Pope, called for him, threw themselves prostrate on the earth before him, and received his blessing in devout silence. Many of the pardoned offenders were still more extravagant in their demonstrations of joy and thankfulness. Among them was Galletti, of Bologna, afterward one of the Pope’s ministers, and most active in those measures which ended in the assassination of Rossi and in driving Pius into exile. He had been sentenced to imprisonment for life, and was kept in the castle of Sant’ Angelo. When released, he threw himself at the Pope’s feet, and swore, by his own heart’s blood and that of his children, that he would be grateful and faithful. Some of the exiles, however, among whom was Mamiani, refused to subscribe the proposed engagement, simple as it was; but they returned after a time to their homes, merely promising allegiance. Every time that the Pope left his palace he was surrounded by a sort of triumphal procession. The whole length of the Corso was decorated when he passed through it, and hundreds of likenesses of him, and of panegyrical compositions, covered the walls. Foremost in getting up these popular celebrations was Angelo Brunetti, afterward so well known by his nickname of “Ciceruacchio.” “He was a person of single mind, rustic in manners, proud and at the same time generous, as is common with Romans of the lower class.” By his industry he had acquired considerable property, and by his liberal use of it had become a leader of the populace, whom he now fired with his own enthusiasm for Pius IX.

[* Luigi Carlo Farini, who is freely quoted by Bowen, was an Italian historian and statesman. His principal work is Storia dello stato Romano dall’ anno 1814 al 1830. — ED.]

The Pope would have been more than man if his head had not been a little turned with all this adulation, which came to him from many foreign lands as well as from Italy. But his simple and modest character bore the trial well; he manifested no undue elation, and formed his plans tranquilly and without hurry for the improvement of his people. Cardinal Gizzi, well known as a friend to reform, and much attached to the Pope, was named Secretary of State; and he wrote letters to the presidents of the provinces, inviting them, the municipal magistrates, ecclesiastics, and all respectable citizens, to prepare and offer schemes for promoting popular education, and especially for the moral, religious, and industrial instruction of the children of the poor. Commissions were appointed to deliberate and advise upon many subjects of proposed reform. Great, indeed, was the need of change in the institutions of the Pontifical States; but the Government had a delicate part to play in amending them, and it wisely determined not to be precipitate in its measures. “Already the Liberals had conceived boundless desires, and the Retrogradists were haunted with unreasonable fears. The Government had, to-day, to moderate on the left, circulate dispatches, well nigh to scold men for hoping too much.”

But the friends of change, says Farini, were for the most part measured in their wishes and cautious in their proceedings; for all prudent men were exerting themselves strenuously to keep the impatient in hand, with excellent effect.

We cannot follow in detail the Pope’s measures down to March, 1848, till which period the movement may be considered as all his own, emanating from his free choice and not from the pressure of outward circumstances or from revolutions in foreign States. He did enough during these twenty months to establish his character as a wise, humane, and liberal sovereign, eager to promote the temporal and religious interests of his people, and prompt to give political power into their hands as fast as they showed themselves capable of using, and not abusing, it. He instituted a civic guard throughout his dominions, modeled on the French National Guard, and disbanded the Gregorian Centurions and volunteers. All his court was opposed to this measure as premature and dangerous; and even Cardinal Gizzi resigned his place in consequence of it. But the Pope persevered, and Cardinal Ferretti, still more inclined to liberalism, was appointed in his place.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.