Such is a general outline of the Roman Constitution spontaneously granted to his subjects by Pius IX.

Continuing Pius IX Flees Rome,

our selection from Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) by Francis Bowen published in 1852. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Pius IX Flees Rome.

Time: 1848

Place: Rome

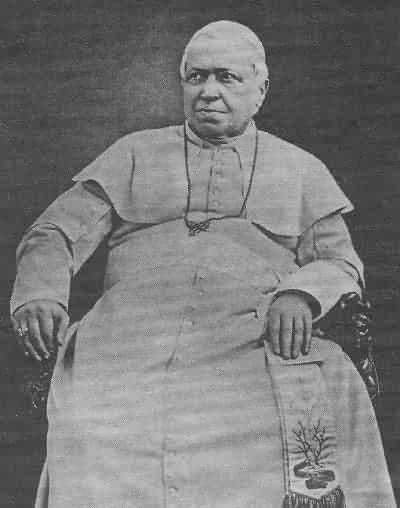

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The judges were to be irremovable after they had held office for three years; and all persons were declared equal in the sight of the law. Extraordinary commissions or tribunals for the trial of offences were abolished. All property, whether of individuals or corporations, whether civil or ecclesiastical, was to be held subject to its equal part of the burdens of the State; and to all bills imposing taxes, the Pope would annex, of his own authority, a special waiver of the ecclesiastical exemption. The administrations of the Provinces and the communes were placed in the hands of their respective inhabitants. The Government (or political) censorship was abolished, but the ecclesiastical censorship was retained.

Such is a general outline of the Roman Constitution spontaneously granted to his subjects by Pius IX. Its merits, in all civil or political matters, are certainly equal, if not superior, to those of the English Constitution, from which in great part it was borrowed; its faults are precisely those which resulted necessarily from the Pope’s double character, as temporal sovereign of the Roman States and as head of the Catholic Church throughout the world. It was not within the province or at the discretion of Pius to alter the tenure by which he held his throne, to change the fundamental principles of the Church or to abolish his ecclesiastical dominion. He granted to his subjects all that was in his power to grant as their temporal sovereign. His purely ecclesiastical relations and duties did not concern them, or concerned them only so far as they were members of the great body of Catholic believers in all lands. The College of Cardinals must choose the Pope, and must choose one of their own number; this is not a law of the Roman States, but a law of the Catholic Church. Pius could not abrogate it; and if he had been inclined to grant everything to his people by divesting himself of the last rag of his sovereignty, the only consequence would have been that the cardinals must have chosen another pope in his place, who might undo all that Pius had accomplished.

These are obvious and necessary considerations; and the Pope expressly recognizes them in the ordinance accompanying the grant of the constitution. “We intend,” he says, “to maintain intact our authority in matters that by their nature are related to the Catholic religion and its rule of morals. And this is due from us as a guaranty to the whole of Christendom, that, in the States of the Church reorganized in this new form, nothing shall be derogated from the liberties and rights of the Church herself, and of the Holy See, nor any precedent be established for violating the sacredness of the religion which it is our duty and mission to preach to the whole world, as the only scheme of covenant between God and man, the only pledge of that heavenly benediction by which states subsist and nations flourish.”

Now, it is worthy of note that neither this constitution nor any of the acts of Pius under it was ever complained of by any party among the Pope’s subjects except in regard to these ecclesiastical reservations which were forced from him by the very nature of the office that he held. The constitutionalists, indeed the moderate reformers, the party of Balbo and Gioberti and D’Azeglio, which comprised most of the educated and reflecting persons in the State, seem to have been entirely satisfied with it as a whole, or as it was. So also were the unthinking populace, who received it with shouts of exultation, so long as they were not moved by the arts of a party who would not be satisfied with having a good pope, but were bent upon having no pope at all. This was the party of Mazzini, the revolutionists as distinguished from the reformers — not strong at first either in numbers or credit, as we have seen, but who made up for all deficiencies by their zeal and activity — who were determined to establish a republic, and who cared nothing for the embarrassments of the Pope’s situation as head of the Church, of indeed for the Church itself. They complained — and with reason, too, upon their principles — of these ecclesiastical reservations; and they made out of them their chief weapon of attack upon the Pope’s government, though they did not profit so much by the use of it as by the evident unwillingness of Pius to rush into a war with Austria for the purpose of giving the sovereignty of Lombardy to Charles Albert, a measure to which he was averse, because he thought such a conflict would be detrimental to the interests of the Church over which he presided.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.