This series has five» easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: O Hapless Louis!.

Introduction

I (Jack Le Moine) think that executing the Louis was where the French Revolution went bad. Previous violence could be attributed to mob excess while official restraints on the king and his family could be attributed to necessary defense to the power of the royal autocrat. Indeed, after the restoration in 1815, the new King began a Reign of Terror all his own. But when the revolutionaries began judicial murders sympathies were divided. Murder and counter-murder. First Louis then Marat.

These tragic scenes, and the opening of the civil war which followed, are depicted by Carlyle in that manner, all his own. You are there experiencing the events with all Carlyle’s emotions towards them and all the horror for after these murders, it became a story of that genre.

This selection is from The French Revolution — A History by Thomas Carlyle published in 1837. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Thomas Carlyle was famous for writing to immerse the reader in history. He imagines being present at the time of he writes of. Interesting technique. People either love or hate his writings.

Time: 1793

Place: France

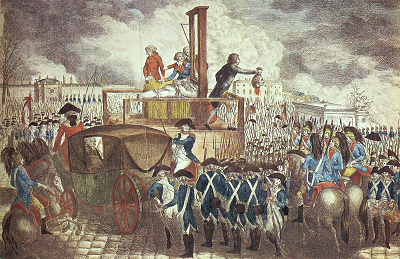

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

To this conclusion, then, hast thou come, O hapless Louis! The Son of Sixty Kings is to die on the Scaffold by form of Law. Under Sixty Kings this same form of Law, form of Society, has been fashioning itself together these thousand years; and has become, one way and other, a most strange Machine. Surely, if needful, it is also frightful, this Machine; dead, blind; not what it should be; which, with swift stroke, or by cold slow torture, has wasted the lives and souls of innumerable men. And behold now a King himself, or say rather Kinghood in his person, is to expire here in cruel tortures; like a Phalaris shut in the belly of his own red-heated Brazen Bull! It is ever so; and thou shouldst know it, O haughty tyrannous man: injustice breeds injustice; curses and falsehoods do verily return “always home,” wide as they may wander. Innocent Louis bears the sins of many generations: he too experiences that man’s tribunal is not in this Earth; that if he had no Higher one, it were not well with him.

A King dying by such violence appeals impressively to the imagination; as the like must do, and ought to do. And yet at bottom it is not the King dying, but the man! Kingship is a coat: the grand loss is of the skin. The man from whom you take his Life, to him can the whole combined world do more? Lally went on his hurdle; his mouth filled with a gag. Miserablest mortals, doomed for picking pockets, have a whole five-act Tragedy in them, in that dumb pain, as they go to the gallows, unregarded; they consume the cup of trembling down to the lees. For Kings and for Beggars, for the justly doomed and the unjustly, it is a hard thing to die. Pity them all: thy utmost pity, with all aids and appliances and throne-and-scaffold contrasts, how far short is it of the thing pitied!

A Confessor has come; Abbe Edgeworth, of Irish extraction, whom the King knew by good report, has come promptly on this solemn mission. Leave the Earth alone, then, thou hapless King; it with its malice will go its way, thou also canst go thine. A hard scene yet remains: the parting with our loved ones. Kind hearts environed in the same grim peril with us; to be left here! Let the Reader look with the eyes of Valet Clery through these glass doors, where also the Municipality watches, and see the cruelest of scenes:

At half-past eight, the door of the anteroom opened: the Queen appeared first, leading her Son by the hand; then Madame Royale and Madame Elizabeth: they all flung themselves into the arms of the King. Silence reigned for some minutes; interrupted only by sobs. The Queen made a movement to lead his Majesty towards the inner room where M. Edgeworth was waiting unknown to them: ‘No,’ said the King, ‘let us go into the dining-room; it is there only that I can see you.’ They entered there; I shut the door of it, which was of glass. The King sat down, the Queen on his left hand, Madame Elizabeth on his right, Madame Royale almost in front; the young Prince remained standing between his Father’s legs. They all leaned toward him, and often held him embraced. This scene of woe lasted an hour and three-quarters; during which we could hear nothing; we could see only that always when the King spoke, the sobbings of the Princesses redoubled, continued for some minutes; and that then the King began again to speak.”

And so our meetings and our partings do now end! The sorrows we gave each other; the poor joys we faithfully shared, and all our lovings and our sufferings, and confused toilings under the earthly Sun, are over. Thou good soul, I shall never, never through all ages of Time, see thee any more!

Never! O Reader, knowest thou that hard word?

For nearly two hours this agony lasts; then they tear themselves asunder. “Promise that you will see us on the morrow.” He promises: Ah yes, yes; yet once; and go now, ye loved ones; cry to God for yourselves and me! It was a hard scene, but it is over. He will not see them on the morrow. The Queen, in passing through the anteroom, glanced at the Cerberus Municipals; and, with woman’s vehemence, said through her tears, “Vous etes tous des scelerats!” (“You are all scoundrels!”)

King Louis slept sound, till five in the morning, when Clery, as he had been ordered, awoke him. Clery dressed his hair. While this went forward, Louis took a ring from his watch, and kept trying it on his finger: it was his wedding-ring, which he is now to return to the Queen as a mute farewell. At half-past six, he took the Sacrament; and continued in devotion, and conference with Abbe Edgeworth. He will not see his Family: it were too hard to bear.

At eight, the Municipals enter: the King gives them his Will, and messages and effects; which they, at first, brutally refuse to take charge of: he gives them a roll of gold pieces, a hundred and twenty-five louis; these are to be returned to Malesherbes, who had lent them. At nine, Santerre says the hour is come. The King begs yet to retire for three minutes. At the end of three minutes, Santerre again says the hour is come. “Stamping on the ground with his right foot, Louis answers: ‘Partons‘ (‘Let us go’).” How the rolling of those drums comes in through the Temple bastions and bulwarks, on the heart of a queenly wife; soon to be a widow! He is gone then, and has not seen us? A Queen weeps bitterly; a King’s Sister and Children. Over all these Four does Death also hover: all shall perish miserably save one; she, as Duchesse d’Angouleme, will live — not happily.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Ireland is like a half-starved rat that crosses the path of an elephant. What must the elephant do? Squelch it – by heavens – squelch it.

– Thomas Carlyle, British essayist, 1840s

Certainly not a character that I would be building my case in opposing the ethics of the French Revolution. Better give his likes and that of Giraldus Cambrensis a wide berth. In fact the French Revolution is probably the purest form of democracy and a beacon of light in the sad world of today that has lost its way. Furthermore, one can rightly assert that the French Revolution is a work in progress. History was not, nor ever will it be a labour of love.

Right, Carlyle was not a good guy. But he sure wrote vividly!