Today’s installment concludes Pius IX Flees Rome,

our selection from Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) by Francis Bowen published in 1852. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of eleven thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Pius IX Flees Rome.

Time: 1848

Place: Rome

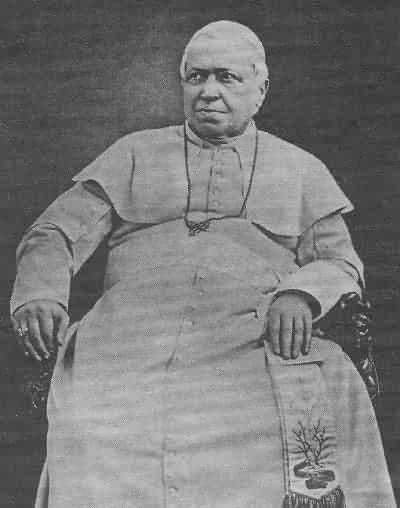

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“In the mean time Rossi’s carriage entered the court of the palace. He sat on the right, and Righetti, Deputy Minister of Finance, on the left. A howl was raised in the court and yard, which echoed even into the hall of the Council. Rossi got out first, and moved briskly, as was his habit in walking, across the short space which leads from the centre of the court to the staircase on the left hand. Righetti, who descended after him, remained behind, because the persons were in the way who caused the outcry, and who, brandishing their cutlasses, had surrounded Rossi and were loading him with opprobrium. At this moment there was seen amid the throng the flash of a poniard, and then Rossi losing his feet and sinking to the ground. Alas! he was spouting blood from a broad gash in the neck. He was raised by Righetti, but could hardly hold himself up, and did not articulate a syllable; his eyes grew clouded, and his blood spurted forth in a copious jet. Some of those, whom I named as clad in military uniform, were above upon the stairs; they came down, and formed a ring about the unhappy man; and when they saw him shedding blood and half lifeless, they all turned and rejoined their companions. He was borne, amid his death-struggle, into the apartments of Cardinal Gazzoli, at the head of the stairs on the left side; and there, after a few moments, he breathed his last.

In leaving the palace of the Cancellaria, one met some faces gleaming with a hellish joy, others pallid with alarm; many townspeople standing as if petrified; agitators, running this way and that, carbineers the same; one kind of men might be heard muttering imprecations on the assassin, but the generality faltered in broken and doubtful accents; some, horrible to relate, cursed the murdered man. Yes, I have still before my eyes the livid countenance of one who, as he saw me, shouted, ‘So fare the betrayers of the people!’ But the city was in the depths of gloom, as under the hand of calamity and the scourge of God; and wherever there were respectable persons, though of liberal and Italian principles, they were horror-struck, and called for the resolute exertions of the authorities.”

When the terrible news came to the Pope, he was struck with horror and dismay, but yet strove to rally the other members of the Government around him and preserve the State from anarchy. But his efforts were miserably seconded; one person after another declined taking office or continuing in it; and even when the presidents of the two Councils were summoned, they had little advice to give. On the morrow the tidings came that a mob was on its way toward the Quirinal, some of the carbineers having fraternized with them, to enforce the appointment of a democratic ministry, and a declaration in favor of a constituent assembly for all Italy. Only a few Swiss, the ordinary guard of honor, were on duty; but they shut the gates of the palace, and nobly declared that their own bodies should be piled up behind them before the rioters should enter. Galletti, the former minister of police, acted as spokesman of the mob, and when admitted to an audience he stated their demands. The Pope indignantly declared that he would not yield to violence, but must deliberate in freedom. This answer only inspired the insurgents with fresh fury, so that they pressed forward to the gates, set one of them on fire, and, mounting upon the roofs of the neighboring houses, opened a fire upon the walls and windows of the Quirinal. The few Swiss fired in return; and then the cry ran through the city that the Pope’s guards were butchering the people, and already there were many slain. Within the palace many advised Pius to yield, a few still spoke of resistance, and the foreign ministers, who were collected there, had no scheme to offer. “The scuffle continues; the worthy prelate, Monsignor Palma, falls dead by the window of his own apartment; balls reach the ante-chamber of the Pope.” At last Pius turned to the diplomatic body who stood around him, and said: “There is no further hope in resistance. Already a prelate is slain in my very palace, shots are aimed at it, artillery leveled. To avoid fruitless bloodshed and increased enormities, we give way; but it is, as you see, only to force. Therefore we protest; let the courts, let your governments, know it. We give way to violence alone, and all we concede is null and void.”

Galletti was then asked to propose his list of ministers, from which the Pope indignantly struck out the name of the Neapolitan Salicetti, but admitted without a word the names of Sterbini, Lunati, and Galletti. Their appointment was signed on the spot, and the news being told to the insurgents “they fired muskets in token of joy, and went off with hymns for Italy and cheers for the Italian Constituent Assembly and the democratic Ministry.”

The next day the club desired that the Swiss should be deprived of their arms and dismissed from the Quirinal; the Pope complied. The club then asked that Galletti should be named general of the carbineers; and he was appointed. “Such was the poltroonery or such the depravity of consciences that no journal would or dared denounce the murder. But why do I speak of denouncing? The murder was honored with illuminations and festivities in numerous cities, and not in these States only, but beyond them, especially at Leghorn.” The Councils met on the 18th and 20th, but not a word was said of the murder, and even a proposition for giving assurance to the Pope “of the devotion and unalterable affection of the Deputies” was voted down. Three of the Bolognese Deputies and a few others then indignantly resigned their seats, and assigned their reasons for this step in addresses to their constituents.

Early on the night of the 25th the Pope secretly left the Quirinal, entered a carriage prepared for him by the wife of the Bavarian ambassador, and went into exile from that city which, within two years and a half, had worshipped, scorned, and assailed him.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Pius IX Flees Rome by Francis Bowen from his article in Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) published in 1852. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Pius IX Flees Rome here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.