. . . it was incompatible with propriety or justice to condemn and punish a religious association, as such, in a place where the Pope held both his own seat and the supreme authority of the Church.

Continuing Pius IX Flees Rome,

our selection from Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) by Francis Bowen published in 1852. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Pius IX Flees Rome.

Time: 1848

Place: Rome

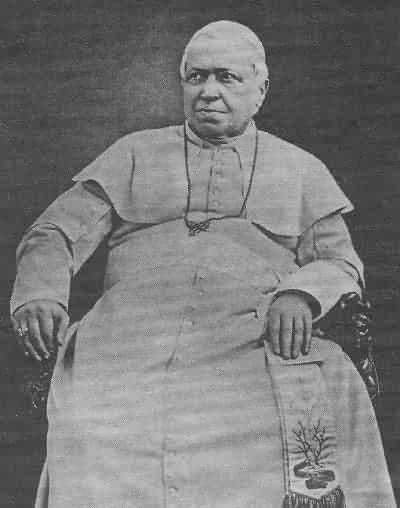

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The world’s future judgment of Pius will depend upon its belief of the sincerity with which he acted in thus allowing nothing but his religious duties and his position as the head of the Church to limit his concessions of political privileges to his subjects. On this point, it is well to hear the opinion of Farini, who, as one of the Mamiani Ministry and as employed to mediate between them and the Pope, because much loved and trusted by him, seems peculiarly qualified to form one without undue bias on either side:

Pius IX had applied himself to political reform, not so much for the reason that his conscience as an honorable man and a most pious sovereign enjoined it, as because his high view of the papal office prompted him to employ the temporal power for the benefit of his spiritual authority. A meek man and a benevolent prince, Pius IX was, as a pontiff, lofty even to sternness. With a soul not only devout, but mystical, he referred everything to God, and respected and venerated his own person as standing in God’s place. He thought it his duty to guard with jealousy the temporal sovereignty of the Church, because he thought it essential to the safe-keeping and the apostleship of the faith.

Aware of the numerous vices of that temporal government, and hostile to all vice and all its agents, he had sought, on mounting the throne, to effect those reforms which justice, public opinion, and the times required. He hoped to give luster to the papacy by their means, and so to extend and to consolidate the faith. He hoped to acquire for the clergy that credit, which is a great part of the decorum of religion and an efficient cause of reverence and devotion in the people. His first efforts were successful in such a degree that no pontiff ever got greater praise.

By this he was greatly stimulated and encouraged, and perhaps he gave in to the seduction of applause and the temptations of popularity more than is fitting for a man of decision or for a prudent prince. But when, after a little, Europe was shaken by universal revolution, the work he had commenced was, in his view, marred; he then retired within himself and took alarm.

In his heart, the pontiff always came before the prince, the priest before the citizen; in the secret struggles of his mind, pontifical and priestly conference always outweighed the conscience of the prince and citizen. And as his conscience was a very timid one, it followed that his inward conflicts were frequent; that hesitation was a matter of course, and that he often took resolutions even about temporal affairs, more from religious intuition or impulse than from his judgment as a man. Added to this, his health was weak and susceptible of nervous excitement — the dregs of his old complaint. From this he suffered most when his mind was most troubled and uneasy; another cause of wavering and changefulness.

Under the pressure of the extraordinary occurrences throughout Europe early in the spring of 1848, the Pope’s new Ministry under the constitution proceeded vigorously and rapidly to give full development and efficiency to that instrument. They also expressed the wish for a firm union of the constitutional thrones of Italy with one another with a view to insuring her independence; and they ordered the papal banners to be decorated with pennons of the Italian tricolor. On March 21st the news of the revolution at Vienna, much magnified by report, arrived, and the excitement of the Roman populace knew no bounds.

Every bell in the city pealed for joy; from palace and from hovel, from magazine and workshop, the townspeople poured in throngs into the streets and squares; some took to letting off firearms, some to strewing flowers; some hoisted flags on the towers, some decked with them their balconies; everybody was shouting ‘Italia! Italia!‘ and cursing the Empire. In an access of fury, the Austrian arms were torn down, dashed to pieces, and befouled amid the applause of the crowd in spite of the dissuasion of the public functionaries and of prudent persons.”

The hostility to the Jesuits now threatened to break out into violence; and for the double purpose of protecting them and appeasing the passions of the mob the Pope consented that the schools which they had superintended should be given into other hands, that their associations should be disbanded and they should be exiled.

The Government perhaps had no choice, so swiftly and impetuously did the torrent of popular commotion roll. I will not affirm that the Pope and the Government ought to have exposed to the last hazard the security of the State for an ineffectual defense of the fraternity. What I wish to observe is that if there were among the Jesuits men stained with guilt, and mischievous plotters, they ought to have been watched and punished as bad citizens; but it was incompatible with propriety or justice to condemn and punish a religious association, as such, in a place where the Pope held both his own seat and the supreme authority of the Church. None but the Pope had the power to condemn the society as a whole, and no condemnation but his could be just or valid in the opinion and conscience of the Catholics, or produce the desired political effects.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.