Pope Pius IX sided with Italians in the war. That made Catholics in Austria and northern countries against him. Military defeat turned Italians against him.

Continuing Pius IX Flees Rome,

our selection from Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) by Francis Bowen published in 1852. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Pius IX Flees Rome.

Time: 1848

Place: Rome

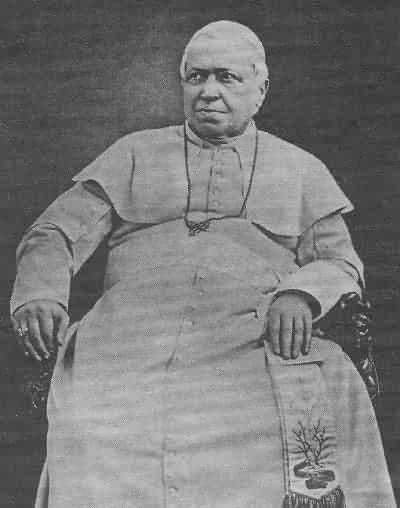

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

He had before this been greatly troubled by the proclamation of General Durando; still he had hoped that the Italian League would be shortly concluded, and that, when he had furnished the quota of troops that might be due from him as a temporal sovereign, he would then have been able, in the capacity of pontiff, to use those good offices which he considered requisite to assure the consciences of Catholics.

Even the news of some reverses to the Italian arms in Lombardy failed to awaken a proper feeling among the inhabitants of Central and Southern Italy, and Farini thus censures the slothfulness and vanity of his countrymen:

Few gave credit or importance at the time to this and other sinister intelligence; the greater part of those who beheld the first marvelous smiles of fortune relied upon the star of Italy, and thought the Empire was dismembered. We Italians are too susceptible to the impulses of passion, and of heat in the imagination; with a small matter we are drunken and think to leap over the moon. Deadly intoxication, most deadly fault, that of undervaluing an enemy, which lets our enthusiasm too easily evaporate, and gives him every facility for showing that he is as gallant as we are, and more resolute; that he has much of perseverance and of discipline — qualities more effectual and valuable than simple courage. It comes to this; we must either send about their business the dreams of poets, and educate ourselves in severe and masculine virtues, or must yet remain long in a position to chant many more elegies, to assuage our sorrow, than hymns of triumph; we must either rest assured that with the tenacious, the disciplined, and the resolute only the tenacious, disciplined, and resolute can cope, and must therefore leave off despising the Austrians, and imitate them in their steadiness and their attention to the military spirit; or else we must be doomed to the disgrace of seeing them masters of our country. A stern truth; but the only one that an Italian freeman can utter to Italians free in mind. He who wants compliments and adulation may fling these warning words from him.”

The Ministry at Rome, driven onward by the popular clamor, represented to the Pope in strong terms the necessity of sending orders to his army to take an active part in the war; for they had not yet commenced hostilities with the Austrians. A consistory of the cardinals was to be held on April 29th; and it was feared that Pius would take that occasion for declaring that he was averse to the war, thus pacifying the minds of the Catholics in Germany. The allocution of the Pope realized these fears, though it expressed only his wish to remain neutral, “and to embrace all kindreds, peoples, and nations with equal solicitude of paternal affection.” But the Ministry resigned in consequence, and great disturbances arose in the city; the populace were not willing themselves to volunteer for the war, but they were determined that the Pope should not continue a man of peace. The Civic Guard was placed under arms, but it was soon found that the soldiers shared the feelings of the people, and no reliance could be placed upon them. Threats were uttered of assassinating the cardinals, and others cried out “to make short work — as they called it — with the government of the priests, those traitors to Italy, and to place Rome under popular sway.” To avert bloodshed, the Pope consented to a compromise; he gave up the entire direction of his troops to Charles Albert, and published, of his own accord, and without the knowledge of his ministers, an affecting remonstrance to his people.

Pius also wrote an earnest letter to the Emperor of Austria, entreating him to put a stop to the war by acknowledging the independence of Venetia and Lombardy. “Let not the generous German nation take it ill,” he said, “if we invite them to lay resentment aside, and to convert into the beneficial relations of friendly neighborhood a domination which could never be prosperous or noble while it depended solely on the sword.” But the prayers of the Pope had now little influence either with the Emperor or with his own subjects; he had long ago forfeited the favor of the Absolutists by his political reforms, and he had now lost the love of his people by his reluctance to gratify their passion for sway.

Yet if he had basely yielded to their wishes, against his judgment and his conscience, he would have injured only the cause of the papacy in foreign lands, and the issue of the war would not have been changed. As it was, his troops were actively engaged in the contest till the time of their capture at Vicenza by the Austrians. The fatal blow was given to the hopes of Italy by the King of Naples withdrawing his troops at a critical moment, when their loss could not be replaced.

Their departure, and the consequent capture of the papal army under Durando at Vicenza, enabled the Austrians to turn their whole force against the Piedmontese, who were then defeated and driven back. The disgraceful capitulation at Milan followed, and the cause of United Italy was lost forever. Brilliant as its promise had been at the outset, the Revolution of 1848 terminated as pitifully as did those of 1820 and 1831; and for its disastrous issue the Italians have none to blame but themselves.

Misfortunes and defeat had their usual effect in inflaming the rage of parties. The personal influence of the Pope could no longer keep the passions of the citizens in check, and the clubs now governed Rome with absolute sway. The party of Mazzini, bent on trying the experiment of a republic at all hazards, began to show its head after a long period of inefficiency and discouragement, and every day acquired new adherents and stronger influence.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.