Several of his friends came and remonstrated with him against such an exposure of his life.

Continuing Pius IX Flees Rome,

our selection from Pius the Ninth and the Revolution at Rome (in the North American Review, volume LXXIV, New Series) by Francis Bowen published in 1852. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Pius IX Flees Rome.

Time: 1848

Place: Rome

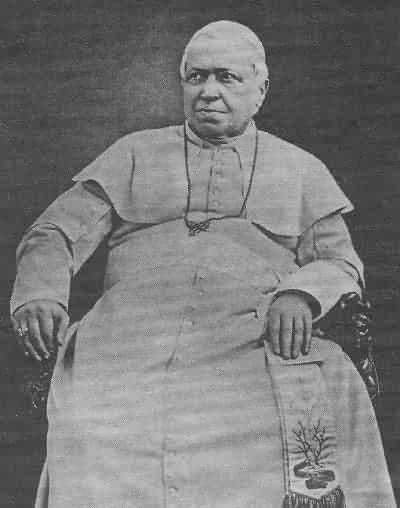

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

He suggested to the Pope that he was probably odious to the court on account of his previous employments and his writings; that some would perhaps look very coldly on a minister who had married a Protestant wife; and that the French Republic might be displeased if he should hold a high post at Rome. But in the middle of September the solicitations of the Pope and of many respectable persons in the State became so urgent that Rossi consented to serve; the opinion was universal that no other person possessed the requisite abilities, character, and experience to carry on the Government at this perilous crisis; and that, if he failed, all indeed was lost. He selected for his colleagues men of liberal politics, but temperate in their opinions. He announced his intention to carry into effect the Fundamental Statute, in all its parts, according to constitutional usage; to counteract and repress both parties opposed to that instrument; to abolish exemptions, restore the finances, and reorganize the army; to conclude a league with Piedmont and Tuscany, even if it should be impossible with Naples; and to fix the contingent of troops which the Pope was to supply, so that he need not in any way mingle in the war.

The turbulent and the presumptuous, “the magistrates accustomed to fatten upon abuses, the Sanfedists who made a livelihood of disorder, and the clergy, greedy of gold and honors, could ill bear that Pellegrino Rossi should have the authority of a minister.” But those who knew the real condition of affairs, and that, unless the finances were improved and public discipline and order restored, all would go to wreck, counted it great gain that he should take charge of the debilitated State. “The dissatisfied were more numerous and noisy in the capital; the contented stronger in the Provinces, especially at Bologna, where an educated community wished for a liberal system, with a government strong in the strength of the law; where the recent terrible events had filled every mind with horror; and where Rossi, the proscribed of 1815, was dear to memory, and rooted in public esteem.”

The Roman Legislature was to meet again in the middle of November, so that the new minister was chiefly occupied with maturing the measures which were to be laid before it for adoption. His public acts therefore were few; but they were enough to show that new wisdom and vigor directed the course of affairs. He obtained the Pope’s consent that the clergy should make a new contribution of two millions of crowns to the State, on the strength of which he obtained a new loan and punctually paid the interest on the public debt. He invited General Zucchi home from Switzerland to take the command of the army, which rapidly improved in discipline under his energetic guidance. He distributed medals to those who had been wounded and to the families of the slain at Vicenza. He established two lines of telegraph, one to Ferrara by the way of Bologna, and another to Civita Vecchia. The negotiations with Sardinia and Tuscany for an Italian league were advanced nearly to completion. Chairs of political economy and commercial law were founded in the universities at Rome and Bologna. Toward the close of October the mob rose in Rome, on occasion of a squabble between a Jew and a Catholic, and threatened to sack the Ghetto and maltreat its inhabitants. Rossi hurried the Civic Guard and the carbineers to the spot, allayed the tumult, arrested and imprisoned some of its ringleaders, and published an energetic proclamation to warn the turbulent that the laws would be enforced.

All these proceedings excited the anger of Rossi’s enemies, the journalists, the captains of the people, and the Roman clubs.” There was no opprobrium that was not heaped upon him, no charge that was not leveled at the Government. But these declamations seemed to have little effect on the body of the people. On the morning of November 15th, when the Legislature was to commence its session, though knots of persons were seen talking in the streets with excited countenances, there was no outbreak or popular tumult. Rossi had received many anonymous letters in which his life was threatened, but he scorned to take any notice of them. This morning one came which directly affirmed that he would be assassinated in the course of the day; and he threw it into the fire. The regulation of the police, now that the day of the session had arrived, belonged to the President of the Council of Deputies; and Rossi, punctilious in the observance of the constitution, refused to give them any orders.

Several of his friends came and remonstrated with him against such an exposure of his life. “To all this he answered that he had taken the measures which he thought suitable for keeping the seditious in order, and that he could not, on account of risk that he might personally run, forego repairing to the Council according to his duty; that perhaps these were idle menaces; but if anyone thirsted for his blood, he would have the means of shedding it elsewhere on some other day, even if, on that day, he should lose his opportunity. He would therefore go.” He was elated by the confidence which the Pope had in him, and expected both trust and aid from the Parliament, to which he was so soon to explain his ideas and intentions.

“When the ordinary hour of the parliamentary sitting, which was about noon, arrived, the people began to gather in the square of the Cancellaria, and by degrees in the courtyard and then in the public galleries of the hall. Soon these were all full. A battalion of the Civic Guard was drawn up in the square; in the court and hall there was no guard greater than ordinary. There were, however, not a few individuals, armed with their daggers, in the dress of the volunteers returned from Vicenza, and wearing the medals with which the municipality of Rome had decorated them. They stood together and formed a line from the gate up to the staircase of the palace. Sullen visages were to be seen and ferocious imprecations heard among them. During the time when the Deputies were slowly assembling, and business could not commence because there was not yet a quorum present, a cry for help suddenly proceeded from the extremity of the public gallery, on which everyone turned thither a curious eye; but nothing more was heard or seen, and those who went to get some explanation of the circumstances returned without success.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.