Today’s installment concludes Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home,

our selection from Anabasis by Xenophon published in around 350 BC. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of seven thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home.

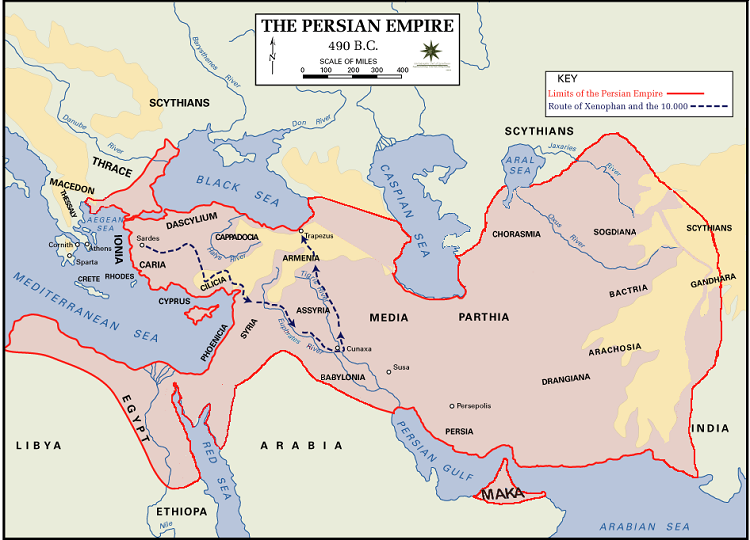

Time: 400 BC

Place: Armenia

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

This plan was approved, and they threw the companies into columns. Xenophon, riding along from the right wing to the left, said: “Soldiers, the enemy whom you see before you is now the only obstacle to hinder us from being where we have long been eager to be. These, if we can, we must eat up alive.”

When the men were all in their places, and they had formed the companies into columns, there were about eighty companies of heavy-armed men, and each company consisted of about eighty men. The peltasts and archers they divided into three bodies, each about six hundred men, one of which they placed beyond the left wing, another beyond the right, and the third in the centre. The generals then desired the soldiers to make their vows to the gods; and having made them, and sung the paean, they moved forward. Chirisophus and Xenophon, and the peltasts that they had with them, who were beyond the enemy’s flanks, pushed on; and the enemy, observing their motions, and hurrying forward to receive them, was drawn off, some to the right and others to the left, and left a great void in the centre of the line; when the peltasts in the Arcadian division, whom Aeschines the Acarnanian commanded, seeing the Colchians separate, ran forward in all haste, thinking that they were taking to flight; and these were the first that reached the summit. The Arcadian heavy-armed troop, of which Clearnor the Orchomenian was captain, followed them. But the enemy, when once the Greeks began to run, no longer stood its ground, but went off in flight, some one way and some another.

Having passed the summit, the Greeks encamped in a number of villages containing abundance of provisions. As to other things here, there was nothing at which they were surprised; but the number of bee-hives was extraordinary, and all the soldiers that ate of the combs lost their senses, vomited, and were affected with purging, and not any of them was able to stand upright; such as had eaten a little were like men greatly intoxicated, and such as had eaten much were like madmen, and some like persons at the point of death. They lay upon the ground, in consequence, in great numbers, as if there had been a defeat; and there was general dejection. The next day no one of them was found dead; and they recovered their senses about the same hour that they had lost them on the preceding day; and on the third and fourth days they got up as if after having taken physic.[1]

[Footnote 1: That there was honey in these parts, with intoxicating qualities, was well known to antiquity. Pliny mentions two sorts of it, one produced at Heraclea in Pontus, and the other among the Sanni or Macrones. The peculiarities of the honey arose from the herbs to which the bees resorted; the first came from the flower of a plant called oegolethron, or goatsbane; the other from a species of rhododendron. Tournefort, when he was in that country, saw honey of this description. Ainsworth found that the intoxicating honey had a bitter taste. This honey is also mentioned by Dioscorides.]

From hence they proceeded two days’ march, seven parasangs, and arrived at Trebizond, a Greek city, of large population, on the Euxine Sea; a colony of Sinope, but lying in the territory of the Colchians. Here they stayed about thirty days, encamping in the villages of the Colchians, whence they made excursions and plundered the country of Colchis. The people of Trebizond provided a market for the Greeks in the camp, and entertained them in the city; and made them presents of oxen, barley-meal, and wine. They negotiated with them also on behalf of the neighboring Colchians, those especially who dwelt in the plain, and from them too were brought presents of oxen.

Soon after, they prepared to perform the sacrifice which they had vowed. Oxen enough had been brought them to offer to Jupiter the Preserver, and to Hercules, for their safe conduct, and whatever they had vowed to the other gods. They also celebrated gymnastic games upon the hill where they were encamped, and chose Dracontius, a Spartan — who had become an exile from his country when quite a boy, for having involuntarily killed a child by striking him with a dagger — to prepare the course and preside at the contests. When the sacrifice was ended, they gave the hides[2] to Dracontius, and desired him to conduct them to the place where he had made the course. Dracontius, pointing to the place where they were standing, said, “This hill is an excellent place for running, in whatever direction the men may wish.”

[Footnote 2: Lion and Kuehner have a notion that these skins were to be given as prizes to the victors, referring to Herodotus, who says that the Egyptians, in certain games which they celebrate in honor of Perseus, offer as prizes cattle, cloaks, and hides. Krueger doubts whether they were intended for prizes, or were given as a present to Dracontius.]

“But how will they be able,” said they, “to wrestle on ground so rough and bushy?”

“He that falls,” said he, “will suffer the more.” Boys, most of them from among the prisoners, contended in the short course, and in the long course above sixty Cretans ran; while others were matched in wrestling, boxing, and the pancratium. It was a fine sight; for many entered the lists, and as their friends were spectators, there was great emulation. Horses also ran; and they had to gallop down the steep, and, turning round in the sea, to come up again to the altar. In the descent, many rolled down; but in the ascent, against the exceedingly steep ground, the horses could scarcely get up at a walking pace. There was consequently great shouting and laughter and cheering from the people.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home by Xenophon from his book Anabasis published in around 350 BC. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home here and here and below.

The Landmark Xenophon’s Hellenika

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.