These were the most warlike people of all that they passed through.

Continuing Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home,

our selection from Anabasis by Xenophon published in around 350 BC. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home.

Time: 400 BC

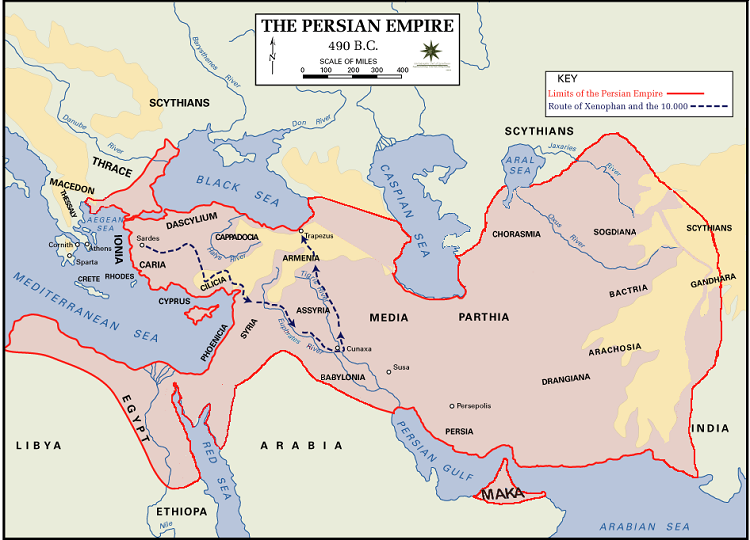

Place: Armenia

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Chirisophus and Xenophon, with Callimachus of Parrhasia, one of the captains, who had that day the lead of all the other captains of the rear-guard, then went forward, all the rest of the captains remaining out of danger. Next, about seventy of the men advanced under the trees, not in a body, but one by one, each sheltering himself as he could. Agasias of Stymphalus, and Aristonymus of Methydria, who were also captains of the rear-guard, with some others were at the same time standing behind, without the trees, for it was not safe for more than one company to stand under them. Callimachus then adopted the following stratagem: he ran forward two or three paces from the tree under which he was sheltered, and when the stones began to be hurled, hastily drew back; and at each of his sallies more than ten cartloads of stones were spent.

Agasias, observing what Callimachus was doing, and that the eyes of the whole army were upon him, and fearing that he himself might not be the first to enter the place, began to advance alone — neither calling to Aristonymus who was next him, nor to Eurylochus of Lusia, both of whom were his intimate friends, nor to any other person — and passed by all the rest. Callimachus, seeing him rushing by, caught hold of the rim of his shield, and at that moment Aristonymus of Methydria ran past them both, and after him Eurylochus of Lusia, for all these sought distinction for valor, and were rivals to one another; and thus, in mutual emulation, they got possession of the place, for when they had once rushed in, not a stone was hurled from above. But a dreadful spectacle was then to be seen; for the women, flinging their children over the precipice, threw themselves after them; and the men followed their example. Æneas of Stymphalus, a captain, seeing one of them, who had on a rich garment, running to throw himself over, caught hold of it with intent to stop him. But the man dragged him forward, and they both went rolling down the rocks together, and were killed. Thus very few prisoners were taken, but a great number of oxen, asses, and sheep.

Hence they advanced, seven days’ journey, a distance of fifty parasangs, through the country of the Chalybes. These were the most warlike people of all that they passed through, and came to close combat with them. They had linen cuirasses, reaching down to the groin, and, instead of skirts, thick cords twisted. They had also greaves and helmets, and at their girdles a short falchion, as large as a Spartan crooked dagger, with which they cut the throats of all whom they could master, and then, cutting off their heads, carried them away with them. They sang and danced when the enemy were likely to see them. They carried also a spear of about fifteen cubits in length, having one spike.* They stayed in their villages till the Greeks had passed by, when they pursued and perpetually harassed them. They had their dwellings in strong places, in which they had also laid up their provisions, so that the Greeks could get nothing from that country, but lived upon the cattle which they had taken from the Taochi.

[*: Having one iron point at the upper end, and no point at the lower for fixing the spear in the ground.]

The Greeks next arrived at the river Harpasus, the breadth of which was four plethra. Hence they proceeded through the territory of the Scythini, four days’ journey, making twenty parasangs, over a level tract, until they came to some villages, in which they halted three days and collected provisions. From this place they advanced four days’ journey, twenty parasangs, to a large, rich and populous city, called Gymnias, from which the governor of the country sent the Greeks a guide to conduct them through a region at war with his own people. The guide, when he came, said that he would take them in five days to a place whence they should see the sea; if not, he would consent to be put to death. When, as he proceeded, he entered the country of their enemies, he exhorted them to burn and lay waste the lands; whence it was evident that he had come for this very purpose, and not from any good-will to the Greeks.

On the fifth day they came to the mountain; and the name of it was Theches. When the men who were in the front had mounted the height, and looked down upon the sea, a great shout proceeded from them; and Xenophon and the rearguard, on hearing it, thought that some new enemies were assailing the front, for in the rear, too, the people from the country that they had burned were following them, and the rear-guard, by placing an ambuscade, had killed some, and taken others prisoners, and had captured about twenty shields made of raw ox-hides with the hair on. But as the noise still increased, and drew nearer, and as those who came up from time to time kept running at full speed to join those who were continually shouting, the cries becoming louder as the men became more numerous, it appeared to Xenophon that it must be something of very great moment. Mounting his horse, therefore, and taking with him Lycius and the cavalry, he hastened forward to give aid, when presently they heard the soldiers shouting, “The sea, the sea!” and cheering on one another.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

The Landmark Xenophon’s Hellenika

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.