The enemy, as you see, is in possession of the pass over the mountains, and it is proper for us to consider how we may encounter them to the best advantage.

Continuing Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home,

our selection from Anabasis by Xenophon published in around 350 BC. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Crisis of Xenophon’s 10,000’s Quest for Home.

Time: 400 BC

Place: Armenia

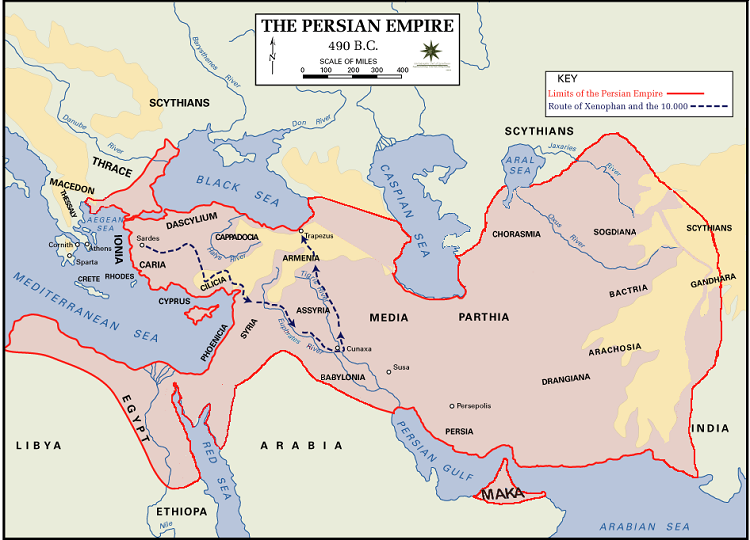

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

When they came to Chirisophus, they found his men also feasting in their quarters, crowned with wreaths made of hay, and Armenian boys, in their barbarian dress, waiting upon them, to whom they made signs what they were to do as if they had been deaf and dumb. When Chirisophus and Xenophon had saluted one another, they both asked the chief man, through the interpreter who spoke the Persian language, what country it was. He replied that it was Armenia. They then asked him for whom the horses were bred, and he said that they were a tribute for the king, and added that the neighboring country was that of Chalybes, and told them in what direction the road lay. Xenophon then went away, conducting the chief back to his family, giving him the horse that he had taken, which was rather old, to fatten and offer in sacrifice (for he had heard that it had been consecrated to the sun), being afraid, indeed, that it might die, as it had been injured by the journey. He then took some of the young horses, and gave one of them to each of the other generals and captains. The horses in this country were smaller than those of Persia, but far more spirited. The chief instructed the men to tie little bags round the feet of the horses and other cattle when they drove them through the snow, for without such bags they sunk up to their bellies.

When the eighth day was come, Xenophon committed the guide to Chirisophus. He left the chief * all the members of his family, except his son, a youth just coming to mature age; him he gave in charge to Episthenes of Amphipolis, in order that if the father should conduct them properly he might return home with him. At the same time they carried to his house as many provisions as they could, and then broke up their camp and resumed their march. The chief conducted them through the snow, walking at liberty. When he came to the end of the third day’s march, Chirisophus was angry at him for not guiding them to some villages. He said that there was none in that part of the country. Chirisophus then struck him, but did not confine him, and in consequence he ran off in the night, leaving his son behind him. This affair, the ill-treatment and neglect of the guide, was the only cause of dissension between Chirisophus and Xenophon during the march. Episthenes conceived an affection for the youth, and, taking him home, found him extremely attached to him.

[*: This is rather oddly expressed, for the guide and the chief were the same person.]

After this occurrence they proceeded seven days’ journey, five parasangs each day, till they came to the river Phasis, the breadth of which is a plethrum. Hence they advanced two days’ journey, ten parasangs, when, on the pass that led over the mountains into the plain, the Chalybes, Taochi, and Phasians were drawn up to oppose their progress. Chirisophus, seeing these enemies in possession of the height, came to a halt, at the distance of about thirty stadia, that he might not approach them while leading the army in a column. He accordingly ordered the other officers to bring up their companies, that the whole force might be formed in line.

When the rear-guard was come up, he called together the generals and captains and spoke to them as follows:

The enemy, as you see, is in possession of the pass over the mountains, and it is proper for us to consider how we may encounter them to the best advantage. It is my opinion, therefore, that we should direct the troops to get their dinner and that we ourselves should hold a council, in the mean time, whether it is advisable to cross the mountain to-day or to-morrow.”

It seems best to me,” exclaimed Cleanor, “to march at once, as soon as we have dined and resumed our arms, against the enemy; for if we waste the present day in inaction the enemy, who are now looking down upon us, will grow bolder, and it is likely that, as their confidence is increased, others will join them in greater numbers.”

After him Xenophon said:

I am of opinion that if it be necessary to fight, we ought to make our arrangements so as to fight with the greatest advantage; but that if we propose to pass the mountains as easily as possible, we ought to consider how we may incur the fewest wounds and lose the fewest men. The range of hills, as far as we see, extends more than sixty stadia in length; but the people nowhere seem to be watching us except along the line of road; and it is, therefore, better, I think, to endeavor to try to seize unobserved some part of the unguarded range, and to get possession of it, if we can, beforehand, than to attack a strong post and men prepared to resist us, for it is far less difficult to march up a steep ascent without fighting than along a level road with enemies on each side; and in the night, if men are not obliged to fight, they can see better what is before them than by day if engaged with enemies; while a rough road is easier to the feet to those who are marching without molestation than a smooth one to those who are pelted on the head with missiles. Nor do I think it at all impracticable for us to steal a way for ourselves, as we can march by night, so as not to be seen, and can keep at such a distance from the enemy as to allow no possibility of being heard. We seem likely, too, in my opinion, if we make a pretended attack on this point, to find the rest of the range still less guarded, for the enemy will so much the more probably stay where they are. But why should I speak doubtfully about stealing? For I hear that you Lacedaemonians, O Chirisophus, such of you at least as are of the better class, practise stealing from your boyhood, and it is not a disgrace, but an honor, to steal whatever the law does not forbid; while, in order that you may steal with the utmost dexterity, and strive to escape discovery, it is appointed by law that, if you are caught stealing, you are scourged. It is now high time for you, therefore, to give proof of your education, and to take care that we may not receive many stripes.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

The Landmark Xenophon’s Hellenika

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.