The raiders were sent home, where the rank and file were very properly released, and the chief officers were condemned to terms of imprisonment which certainly did not err upon the side of severity.

Continuing The Boer War,

with a selection from The Great Boer War by Arthur Conan Doyle published in 1902. This selection is presented in 2 installments, both 5 minutes long and another half that. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Boer War.

Time: 1902 (ended)

Place: South Africa

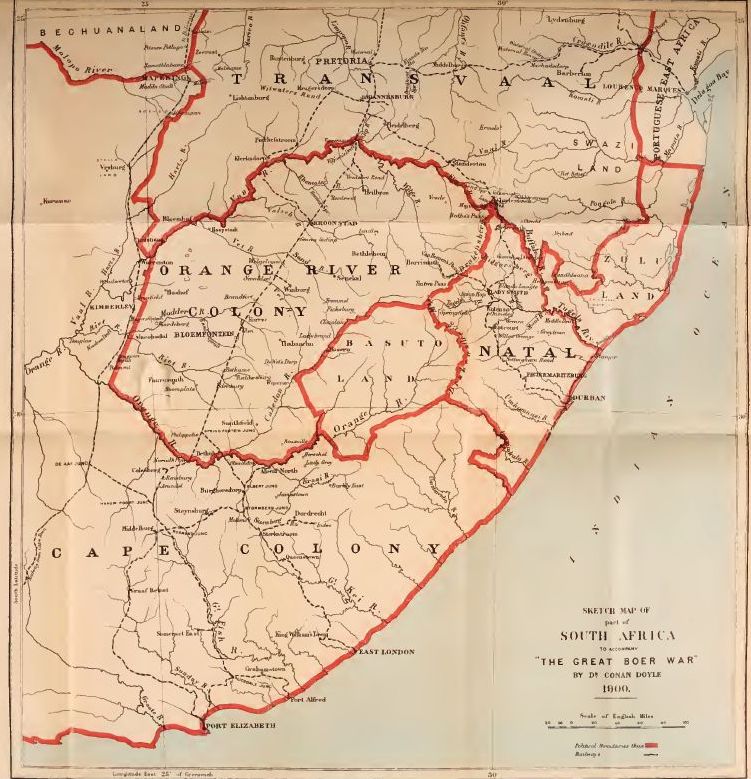

Public domain image from Arthur Conan Doyle’s book in Gutenberg.org.

It had been arranged that the town was to rise upon a certain night; that Pretoria should be attacked, the fort seized, and the rifles and ammunition used to arm the Uitlanders. It was a feasible device, though it must seem to us, who have had some experience of the military virtues of the burghers, very desperate. But it is conceivable that the rebels might have held Johannes burg until the universal sympathy which their cause excited throughout South Africa would have caused Great Britain to intervene. Unfortunately they had complicated matters by ask ing for outside help. Mr. Cecil Rhodes was Premier of the Cape, a man of immense energy, who had rendered great services to the empire. The motives of his action are obscure — certainly, we may say that they were not sordid, for his thoughts always had been large and his habits simple. But whatever that may have been — whether an ill-regulated desire to consolidate South Africa under British rule, or a burning sympathy with the Uitlanders in their fight against injustice — it is certain that he allowed his lieutenant, Dr. Jameson, to assemble the mounted police of the Chartered Company, of which Rhodes was founder and director, for the purpose of cooperating with the rebels at Johannesburg. Moreover, when the revolt at Johannesburg was postponed on account of a disagreement as to which flag they were to rise under, it appears that Jameson (with or without the orders of Rhodes) forced the hand of the conspirators by invading the country with a company absurdly inadequate to the work he had in hand. Five hundred policemen and three field-guns made up the forlorn hope that set out from Mafeking and crossed the Transvaal border December 29, 1895. On January 2d they were surrounded by the Boers amid the broken country near Dornkop, and after losing many of their number, killed or wounded, without food and with spent horses, they were compelled to lay down their arms. Six burghers lost their lives in the skirmish.

On the one hand, the British Government disowned Jameson entirely, and did all it could to discourage the rising; on the other, the President had the raiders in his keeping at Pretoria, and their fate depended upon the behavior of the Uitlanders. They were led to believe that Jameson would be shot unless they laid down their arms, though, as a matter of fact, Jameson and his people had surrendered upon a promise of quarter. So skillfully did Kruger use his hostages that he succeeded, with the help of the British Commissioner, in getting the thousands of excited Johannesburgers to lay down their arms without bloodshed. Completely outmaneuvered by the astute old President, the leaders of the reform movement used all their influence in the direction of peace, thinking that a general amnesty would follow; but the moment that they and their people were helpless the detectives and armed burghers occupied the town, and sixty of their number were hurried to Pretoria jail.

To the raiders themselves the President behaved with great generosity. Perhaps he could not find it in his heart to be harsh to the men who had managed to put him in the right and won for him the sympathy of the world. His own illiberal and oppressive treatment of new-comers was forgotten in the face of this illegal inroad of filibusters. The true issues were so obscured by this intrusion that it has taken years to clear them, and perhaps they never will be wholly cleared. Many persons forgot that it was the bad government of the country which was the real cause of the unfortunate raid. From that time the government might grow worse and worse, but it was always possible to point to the raid as justifying everything. Were the Uitlanders to have the franchise? How could they expect it after the raid? Would Britain object to the enormous importation of arms and obvious preparations for war? They were only precautions against a second raid. For years the raid stood in the way, not only of all progress, but of all remonstrance. Through an action over which they had no control, and which they had done their best to prevent, the British Government was left with a bad case and a weakened moral authority.

The raiders were sent home, where the rank and file were very properly released, and the chief officers were condemned to terms of imprisonment which certainly did not err upon the side of severity. Cecil Rhodes was left unpunished; he retained his place in the Privy Council, and his Chartered Company continued to have a corporate existence. This was illogical and inconclusive. As Kruger said, ” It is not the dog that should be beaten, but the man that set him on to me.” Public opinion — in spite of, or on account of, a crowd of witnesses — was ill informed upon the exact bearings of the question, and it was obvious that as Dutch sentiment at the Cape appeared already to be thoroughly hostile to England it would be dangerous to alienate the British Africanders also by making a martyr of their favorite leader. But whatever arguments may be founded upon expediency, it is clear that the Boers bitterly resented, with justice, the immunity of Rhodes.

In the meantime both President Kruger and his burghers had shown a greater severity to the political prisoners from Johannes burg than to the armed followers of Jameson. The nationality of these prisoners is interesting and suggestive. There were twenty-three Englishmen, sixteen South Africans, nine Scotch men, six Americans, two Welshmen, one Irishman, one Australian, one Hollander, one Bavarian, one Canadian, one Swiss, and one Turk. The prisoners were arrested in January, but the trial did not take place until the end of April. All were found guilty of high treason. Mr. Lionel Phillips, Colonel Rhodes (brother of Mr. Cecil Rhodes), George Farrar, and Mr. Hammond, the American engineer, were condemned to death, a sentence which was commuted to the payment of an enormous fine. The other prisoners were condemned to two years’ imprisonment, with a fine of two thousand pounds each.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Arthur Conan Doyle begins here. James F.J. Archibald begins here. J. Castell Hopkins begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.