So far as Canada was concerned, its action seems to have been partly a product of the sentiment of military pride which was first aroused by the gathering of Canadian troops to subdue the Northwest insurrection of 1885.

Continuing The Boer War,

with a selection from Canada; The Story of the Dominion by J. Castell Hopkins published in 1901. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Boer War.

Time: 1902 (ended)

Place: South Africa

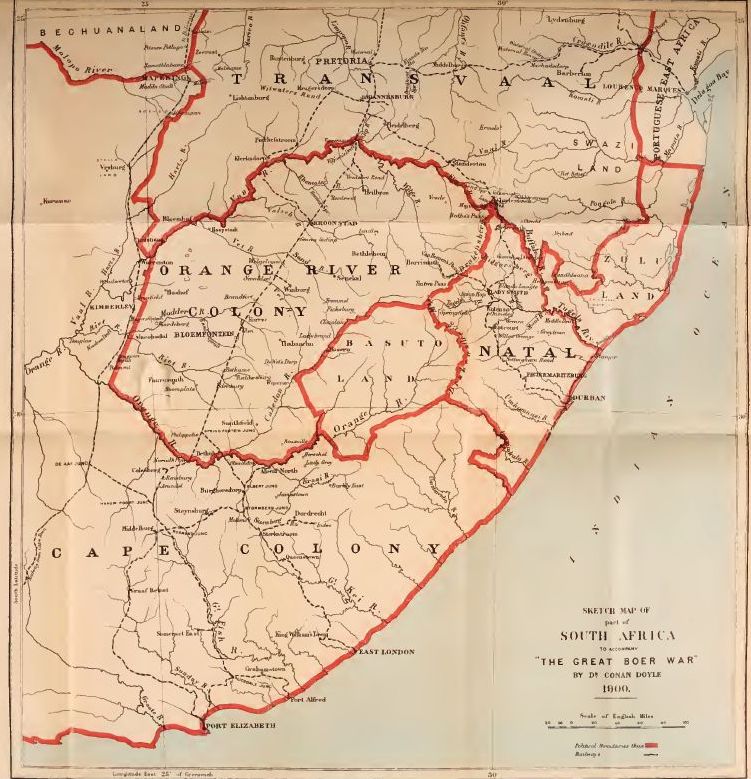

Public domain image from Arthur Conan Doyle’s book in Gutenberg.org.

The contingents that went from Canada to participate in the South African War of 1899-1902 were the effect, not the cause, of Canadian imperialism. The sentiment concerning the war, in the Dominion as in every other part of the empire, was the arousing of a dormant but undoubtedly existent loyalty, and could not, therefore, be the cause of an expressed and evident devotion to crown and empire. Yet the war did the service which perhaps nothing else could have done in proving the existence of this imperial sentiment to the most shallow observer or hostile critic; in arousing it to heights of enthusiasm never dreamed of by the most fervent imperialist; in rendering it possible for statesmen to change many a pious aspiration into practical action or announced policy; in making the organized defense of the empire a future certainty, and its somewhat shadowy system of union a visible fact to the world at large.

So far as Canada was concerned, its action seems to have been partly a product of the sentiment of military pride which was first aroused by the gathering of Canadian troops to subdue the Northwest insurrection of 1885; partly a consequence of the growth of a Canadian sentiment which is local in scope and character, yet curiously anxious to make the Dominion known abroad and peculiarly sensitive to British opinion and approbation; partly an outcome of genuine loyalty among the people to British institutions and to the crown as embodied in the personality and prestige of the Queen; partly a result of the shock to sensitive pride which came from seeing the soil of the empire in South Africa invaded by the Boers, and the position of the motherland in Europe threatened by a possible combination of hostile Powers. Upon the surface this last-mentioned cause was the principal and most prominent one.

There was no considerable precedent for the proffer of troops to the Imperial Government. During the Crimean War nothing had been done by the disorganized provinces except the voting of a sum of money for widows and orphans and the enlistment of the Hundredth Regiment. During the Sudan War, in 1885, a small body of Canadian volunteers and voyageurs, paid from imperial funds and enlisted by request of the British commander, had gone up the Nile in Lord Wolseley’s expedition, under the immediate command of Lieutenant- Colonel F. C. Denison.

More important, however, as a factor in this and other developments of an imperial nature, was the work done by the Imperial Federation League in Canada during the years following 1885. That organization and its leaders had drawn persistent attention, in speeches and pamphlets and magazines and newspaper articles, to the change of sentiment that had come over the public men of Great Britain in connection with empire affairs; to the greatness of the empire in extent, in population, in resources, in power, and in political usefulness to all humanity; to the necessity and desirability of closer union.

The indirect effect of the league’s work in England and in Canada became visible in many directions, and strongly aided a development along imperial lines which has since become marked and continuous. Canada took part in the Indian and Colonial Exhibition of 1886, in the Imperial Conference of 1887, in the organization of the Imperial Institute, in the calling of the Colonial Conference of 1894 at Ottawa, in movements looking to imperial cables, imperial penny postage, imperial tariffs, and imperial steamship lines. But nothing of a military nature was advocated, and the point was in fact almost tabooed. The leaders of the league in London, in Melbourne, or in Toronto were equally afraid to touch a portion of the general problem which was obviously so far in advance of colonial public opinion as to render its advocacy dangerous to the cause. The events of 1899 were therefore all the more remarkable.

In the case of the Transvaal imbroglio, Canada felt a special attraction from the first on account of its being a racial matter, of a kind which the Dominion had encountered more than once and disposed of successfully.

There was among military men a strong desire to raise some kind of volunteer force for active service, and Lieutenant- Colonel S. Hughes, M.P., was particularly enthusiastic. He introduced the subject in Parliament, on July 12th, while negotiations were still pending between President Kruger and Mr. Chamberlain. The result was that, despite the fact that Queensland had already offered troops, and his own expression of opinion that five thousand men would readily volunteer in Canada, it was thought best not to take any immediate action, and the Premier, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, expressed the hope and belief that, in view of the absolute justice of the Uitlanders’ claims, recognition would eventually be given them and war averted. On July 31st more definite action was taken, and the following resolution, moved in the House of Commons by Sir Wilfrid Laurier and seconded by the Hon. G. E. Foster in the absence but with the approval of Sir Charles Tupper, as leader of the Opposition, was carried unanimously:

“That this House has viewed with regret the complications which have arisen in the Transvaal Republic, of which her Majesty is suzerain, from the refusal to accord to her Majesty’s subjects now settled in that region an adequate participation in its government. That this House has learned with still greater regret that the condition of things there existing has resulted in intolerable oppression and has produced great and dangerous excitement among several classes of her Majesty’s subjects in her South African possessions. That this House, representing a people which has largely succeeded by the adoption of the principle of conceding equal political rights to every portion of the population, in harmonizing estrangements, and in producing general content with the existing system of government, desires to express its sympathy with the efforts of her Majesty’s Imperial authorities to obtain for the subjects of her Majesty who have taken up their abode in the Transvaal such measure of justice and political recognition as may be found necessary to secure them in the full possession of equal rights and liberties.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Arthur Conan Doyle begins here. James F.J. Archibald begins here. J. Castell Hopkins begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.