Lord Roberts invited Mrs. Botha to dinner one night, soon after the occupation of Pretoria, and she accepted the invitation.

Continuing The Boer War,

with a selection from Blue Shirt and Khaki by James F.J. Archibald published in 1901. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long and another (the first one) half that. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Boer War.

Time: 1902 (ended)

Place: South Africa

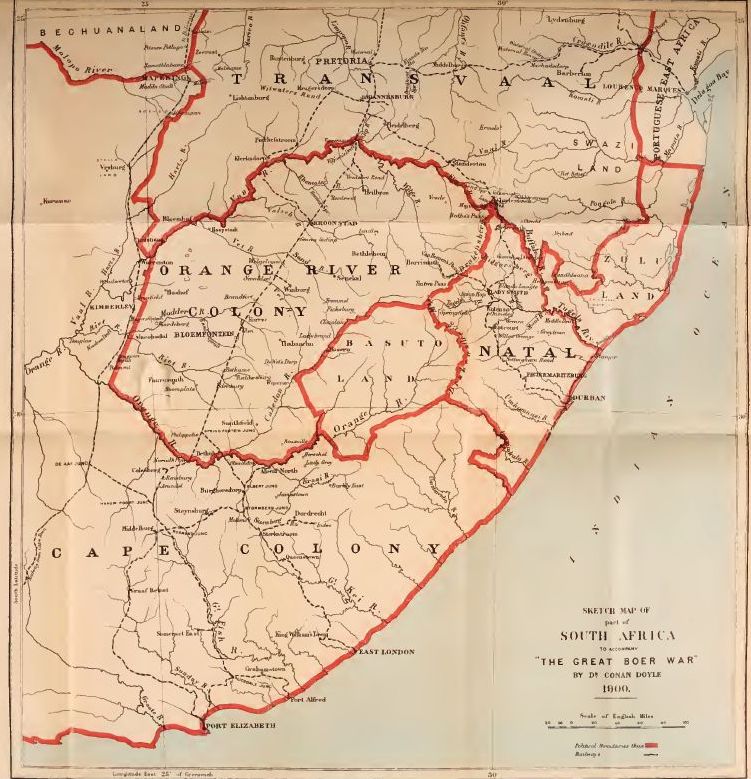

Public domain image from Arthur Conan Doyle’s book in Gutenberg.org.

The burghers had but six guns with which to oppose the advance, and they were small field-pieces that could not be put into action until the enemy advanced almost within rifle range. A little before dark the fighting was heavy all along the line, and then the British became fully convinced that there would be a determined defense at Pretoria. They were very much disappointed when they discovered that the burghers had waived the defense and had saved themselves for a struggle under other conditions. All day long two of the guns shelled one of the forts that had long since been abandoned, but as it was an advantageous position from which to witness the fighting, some of the townspeople had gone up there in the forenoon. These persons were seen by the British, and were naturally mistaken for soldiers, consequently they were subjected to a harmless shell fire. In the afternoon the invaders brought a large number of their guns into action, and the shells flew thick and fast over our position, occasionally striking and exploding at the crest under which we were lying. Considering the number of shells, however, very little damage was done.

All through the day the two wings of Lord Roberts’s army kept extending farther around the town, and just before dark the retreat from the defenses began. As the entire force of burghers was compelled to take one narrow road between the hills, this was crowded with horsemen, each man trying to pass the others, although with no great excitement. There was no talking in the procession; the men rode along looking like an army of spirits in the white clouds of dust. Mingled with the horsemen were men on bicycles, whose clothing showed that they had taken no part in the campaign; men on foot, who had come out to witness the fight, and even men in wagons. Occasionally a gun rumbled along. All were bent on getting into Pretoria as soon as possible. Once there, however, they seemed in no hurry to leave, many remaining until the next morning, after the British had actually entered the town.

Many remained in Pretoria and allowed themselves to be taken, afterward taking the oath of neutrality. Only those who wished to fight it out went on. The faint-hearted ones who stayed behind were snubbed by all the women-folk who knew them, and there is no doubt that many who broke their oath of neutrality and again took to the field did so in order to escape the taunts of the patriotic women.

Lord Roberts and his staff rode into the railway-station, where they dismounted and made arrangements for the formal entry and occupation, which was to occur that afternoon. The hour set was two o’clock, but it was twenty minutes past that hour when the flag raised. The square had been cleared long before that by a battalion of the Guards, and finally the field marshal and his staff rode in and took a position just opposite the entrance to the State Building. Immediately after his entry the drums and fifes and a few pieces of brass played the national anthem, and everyone saluted, but no flag was to be seen at that moment. Finally a murmur started and circulated throughout the ranks and the crowd. “There it is!” exclaimed someone. “Where?” asked another. “On the staff; it’s up.” “No, that can’t be.” “Yes, it really is the flag.” And it was.

As soon as Lord Roberts took possession, he issued a conciliatory proclamation, telling the burghers who wished to lay down their arms and take the oath binding them to neutrality that they would not be made prisoners of war. A number availed themselves of this offer, and most of them kept their promises; but subsequent events made many of them take up arms again.

The execution of young Cordua for conspiracy did much to help the Boer cause by reviving fainting spirits with the spur of new indignation. Everyone in Pretoria knew that there had been no plot whatever, and that the rumors of the supposed conspiracy had been spread by the agents of the British Government. The young man was known to be simple-minded and therefore was not responsible for his actions, but his death was a great stimulus to those fighting for the Boer cause. The proclamation regarding the burning and destroying of all farms in the vicinity of a railroad or telegraph line that was cut also sent many men back into the field and made many new recruits. No matter how loyal a feeling a farmer might have toward the English, he could not prevent someone from coming down from the hills in the night and blowing up the tracks or bridges somewhere within ten miles of his home; but if this happened his house was burned, and almost invariably the burghers who were thus deprived of their homesteads went on commando to stay to the end.

The women of Pretoria were intensely bitter against the British, and did not scruple to show it. For several days not one was seen on the streets. After a time they came out of their houses, but very seldom would they have anything to say to the invaders. They showed the same spirit said to have been shown by our colonial women toward the British, the same that the women of the Southern States showed toward the Northern soldiers, and the same that the Frenchwomen felt against the Germans. In their hearts was bitter hatred, but politeness and gentle breeding toned their actions to suavity that was sometimes mistaken for weakness by a race that never has been noted for its subtle sense of discrimination.

Lord Roberts invited Mrs. Botha to dinner one night, soon after the occupation of Pretoria, and she accepted the invitation. Immediately the rumor was spread throughout the army, and was construed by the British to mean that General Botha was about to surrender at once, and that his wife had persuaded him to do so. On the contrary, Mrs. Botha told me that if he did surrender as long as there was a possible chance to fight, she never would speak to him again. Her eyes flashed and her manner was very far from that of a woman who was weakening because she had dined with the commander-in-chief. She obviously had her reasons for doing it, and there is no doubt that General Botha heard all that went on from herself the next morning. The system of communication between the burghers in the field and their families was facile and well conducted, and the women kept the men informed of every move of the British.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Arthur Conan Doyle begins here. James F.J. Archibald begins here. J. Castell Hopkins begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.