The night I arrived in Pretoria the train reached the station just after dark, and the street lights gave the place an air of mystery.

Continuing The Boer War,

with a selection from The Great Boer War by Arthur Conan Doyle published in 1902. This selection is presented in 2 installments, both 5 minutes long and this one half that.

Then a selection from Blue Shirt and Khaki by James F.J. Archibald published in 1901. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long and another (this one) half that.

Previously in The Boer War. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Time: 1902 (ended)

Place: South Africa

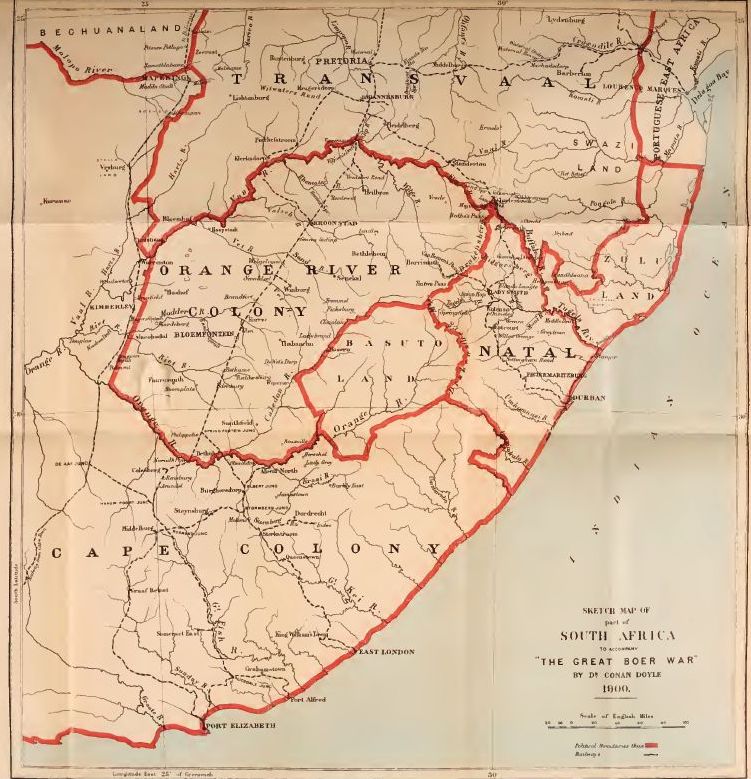

Public domain image from Arthur Conan Doyle’s book in Gutenberg.org.

The imprisonment was of the most arduous and trying sort, and was embittered by the harsh ness of the jailer, Du Plessis. One of the unfortunate men cut his throat, and several fell seriously ill, the diet and the sanitary conditions being equally unhealthful. At last, at the end of May, all the prisoners but six were released. Four of the six soon followed, two stalwarts, Sampson and Davies, refusing to sign any petition and remaining in prison until they were set free in 1897. Altogether the Transvaal Government received in fines from the reform prisoners the enormous sum of two hundred twelve thou sand pounds. A certain comic relief was immediately afterward given to so grave an episode by the presentation of a bill to Great Britain for one million six hundred seventy- seven thousand nine hundred thirty-eight pounds three shillings three pence — the greater part of which was under the heading of moral and intellectual damage.

The grievances of the Uitlanders became heavier than ever. The one power in the land to which they had been able to appeal for some sort of redress amid their grievances was the law courts. Now it was decreed that the courts should be dependent on the Volksraad. The Chief Justice protested against such a degradation of his high office, and he was dismissed in consequence without a pension. The judge who had condemned the reformers was chosen to fill the vacancy, and the protection of a fixed law was withdrawn from the Uitlanders.

A commission appointed by the State was sent to examine into the condition of the mining industry and the grievances from which the new-comers suffered. The chairman was Mr. Schalk Burger, one of the most liberal of the Boers, and the proceedings were thorough and impartial. The result was a report which would have gone a long way toward satisfying the Uitlanders. With such enlightened legislation their motives for seeking the franchise would have been less pressing. But the President and his Raad would have none of the recommendations of the commission. The rugged old autocrat declared that Schalk Burger was a traitor to his country because he had signed such a document, and a new reactionary committee was chosen to report upon the report. Words and papers were the only outcome of the affair. No amelioration came to the new-comers. But they at least had again put their case publicly upon record, and it had been approved by the most respected of the burghers. Gradually in the press of the English-speaking countries the raid was ceasing to obscure the issue. More and more clearly it was com ing out that no permanent settlement was possible where the majority of the population was oppressed by the minority. They had tried peaceful means and failed. They had tried warlike means and failed. What was left for them to do? Their own country, the paramount power of South Africa, had never helped them. Perhaps if it were directly appealed to it might do so. It could not, if only for the sake of its own imperial prestige, leave its children forever in a state of subjection. The Uitlanders determined upon a petition to the Queen, and in doing so they brought their grievances out of the limits of a local controversy into the broader field of international politics. Great Britain must either protect them or acknowledge that their protection was beyond her power. A direct petition to the Queen praying for protection was signed in April, 1899, by twenty-one thousand Uitlanders. From that time events moved inevitably toward the one end. Sometimes the surface was troubled and sometimes smooth, but the stream always ran swiftly and the roar of the fall sounded ever louder in the ears.

Now James Archibald

Before the British advance reached Johannesburg one would never have known, by merely taking note of the life in Pretoria, that a fierce war was being waged in the country. The ladies went on with their calling and shopping, business-houses carried on their work as usual, and the hotels were crowded with a throng of men who looked more like speculators in a new country than men fighting for their homes and liberty.

The night I arrived in Pretoria the train reached the station just after dark, and the street lights gave the place an air of mystery. The blackness of the night heightened one’s imagination of possible plots and attempted escapes, of spies and sudden at tacks. A big Scotchman, who told me his name was “Jack,” shared the compartment with me; he was returning from the front, where he had been fighting for his adopted country. He carried a Mauser, and over his shoulder was slung a bandolier of cartridges; these, with his belt and canteen, made up his entire equipment. His pockets were his haversack, his big tweed coat was his blanket. He gave me the first idea of the real bitterness of the struggle, for he said he would rather die many times over than give up to the British. He was fighting against men of his own blood, perhaps his very relatives; but the spirit of liberty was in him, and he was defending the home he had built in this far-away land.

At the hotel I was reminded of the gatherings in a California “boom town” house or of a Colorado mining-camp. There were men of all nations and in all sorts of dress; but the prevalence of top-boots and leggins gave to the gathering a peculiarly Western look. Rifles stood in the corners of the room, but except for this item nothing about the men denoted their connection with the war. They were nearly all speaking English. By that time I began to feel that I had been cheated, for I wished to hear some Dutch. It is a fact, however, that in all my stay in the Transvaal I found no use for any tongue but my own.

When I first met the family of Secretary Reitz I asked a little boy of about ten if he spoke English.

“No, sir,” he exclaimed with emphasis; “we don’t speak English down here — we speak American.”

During the few weeks before the British occupation of Pretoria, there was hardly a ripple of excitement among the people; in fact, there was more South African war talk in Washington and New York when I left the United States than I heard in the capital of the Republic most interested.

My last meeting with President Kruger was on the occasion of the presentation of the celebrated message of sympathy from thirty thousand Philadelphia schoolboys. The voluminous document was delivered by James Smith, a New York district-messenger boy, who was accompanied by one of the editors of a Philadelphia newspaper, Mr. Hugh Sutherland.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Arthur Conan Doyle begins here. James F.J. Archibald begins here. J. Castell Hopkins begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.