On that well-fought field Texan independence was won.

Today’s installment concludes The Texas Rebellion,

the name of our combined selection from Sam Houston and Charles Edwards Lester. The concluding installment, by Charles Edwards Lester from Houston and His Republic, was published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed seven thousand words from the great works of history. Congratulations!

Previously in The Texas Rebellion.

Time: 1836

Place: Texas

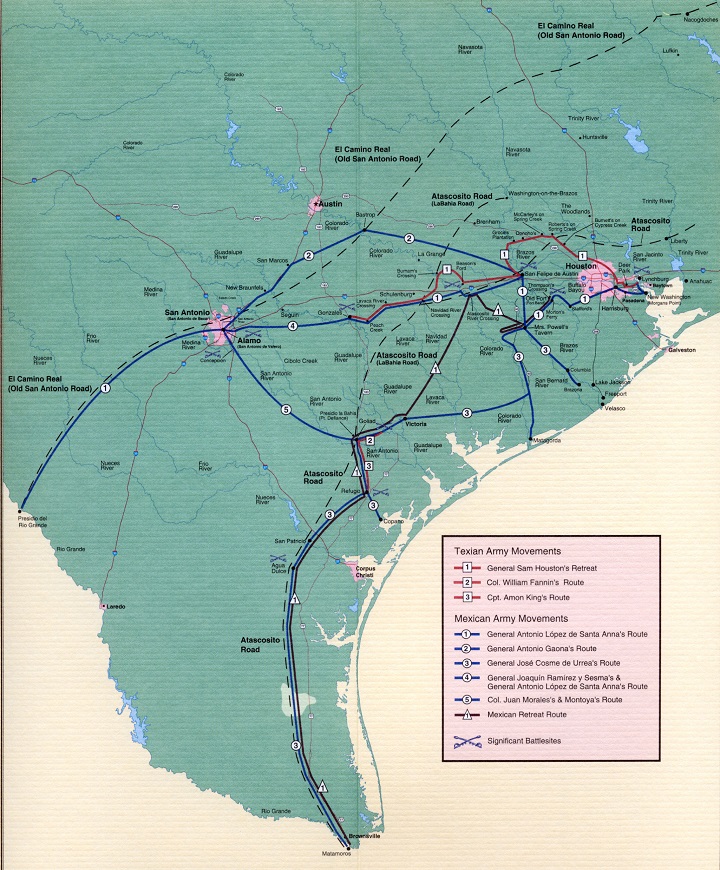

Public domain image from Texas Revolution Maps.

The flight had now become universal. The Texans had left dead and dying on the ground where the battle began (more Mexicans than their own entire number), and far over the prairie they were chasing the flying and following up the slaughter. Many were overtaken and killed as they were making their escape through the high grass. The Mexican cavalry was well mounted, and after the defeat they spurred their horses and turned their heads toward Vince’s bridge. They were hotly pursued by the victors, and when the latter came up the most appalling spectacle perhaps of the entire day was witnessed.

When the fugitive horsemen saw that the bridge was gone, some of them, in their desperation, spurred their horses down the steep bank; others dismounted and plunged into the stream; some were entangled in their trappings, and were dragged down with their struggling steeds, others sank at once to the bottom; while those whose horses reached the opposite bank fell backward into the river. In the meantime, while they were struggling with the flood, their pursuers, who had come up, were pouring down upon them a deadly fire which cut off all escape. Horses and men, by hundreds, rolled down together; the water was red with their blood and filled with their struggling bodies. The deep, turbid stream was literally choked with the dead.

A similar spectacle was witnessed on the southern verge of the island of trees, near the Mexican encampment, in the rear of the battle-ground. There was little chance of escape in this quarter, for a deep morass had to be passed, and yet a great number of the fugitives, in their desperation, had rushed to this spot as a forlorn hope. They had plunged into the water and mud with horses and mules, and, in attempting to cross, had been completely submerged; those who seemed likely to escape soon fell victims to the unerring aim of a practiced rifleman until the morass was literally bridged over with carcasses of dead mules, horses, and men.

A company of about two hundred fifty cooler and braver men, under Almonte, had rallied in the island of trees, prepared to resist or surrender rather than fly. Houston rallied as large a body of men as could be assembled and was preparing to lead them to the charge, when his gallant horse, that had so nobly borne his rider through the thickest of the battle, with seven bullets in his body, at last staggered and fell dead. Houston, in dismounting, struck upon his wounded leg and fell to the earth. It was now discovered, for the first time, that he was wounded. Alarm immediately spread over the field. Houston called for General Rusk, and gave him the command. He was then helped upon another horse, and General Rusk advanced with his newly formed company upon the last remnant of the Mexican army. Its commander, however, came promptly forward and surrendered his sword. Houston then cast a glance over the field and said, “I think now, gentlemen, we are likely to have no more trouble to-day, and I believe I will return to the camp.”

The party then rode slowly off from the field of victory and the resting-place of the dead, and returned to the oak at whose foot the hero of San Jacinto had slept till the “sun of Austerlitz” had awakened him that morning. All resistance to the arms of Texas ceased. The pursuers returned to the camp, where a command was left to guard the spoils taken from the enemy. As the Commander-in-Chief was riding across the field the victorious soldiers came up in crowds, and slapping him rudely on his wounded leg, exclaimed “Now, aren’t we brave fellows, General?”

“Yes, boys, you have covered yourselves with glory, and I decree to you the spoils of victory; I will reward valor. I claim only to share the honors of our triumph with you! ”

While he was giving his orders, after he reached the Texas encampment and before he had dismounted, General Rusk came in and presented his prisoner, Almonte. It was the first time they had ever met. This seemed to give a finishing stroke to the victory, and Houston, who was completely exhausted from fatigue and loss of blood, fainted and fell from his horse. Colonel Hockley caught him in his arms and laid him at the foot of the oak.

Thus ended the bloody day of San Jacinto — a battle that has scarcely a parallel in the annals of war. The immediate fruits of victory were not small, as the spoils were of great value to men who had nothing in the morning but the arms they carried; scanty, coarse clothing, and the determination to be free. About nine hundred stands of English muskets (besides a vast number that were lost in the morass and bayou), three hundred sabers, two hundred pistols, three hundred valuable mules, and a hundred fine horses; a large amount of provisions, clothing, tents, and paraphernalia for officers and men; and twelve thousand dollars in silver, constituted the spoil taken from the enemy.

On that well-fought field Texan independence was won. A brave but outraged people, in imitation of their fathers of the century before, had entrusted their cause to the adjudication of battle, and had gained the victory. It was not a struggle for the aggrandizement of some military chieftain, nor was it a strife for empire. The soldiers who marched under the “Lone Star” into that engagement were free, brave, self-relying men. Some of them, indeed, had come from a neighboring Republic, as Lafayette crossed the sea to join in the struggle for freedom, but most of them were men who cultivated the soil they fought on, and had paid for it with their money or their labor. Hundreds of them had abandoned their homes to achieve everlasting freedom for their children. They were fighting for all that makes life worth living or gives value to its possession.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our selections on The Texas Rebellion by two of the most important authorities of this topic:

- a Speech by Sam Houston.

- Houston and His Republic by Charles Edwards Lester published in 1846.

Sam Houston begins here. Charles Edwards Lester begins here.

This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Texas Rebellion here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.