It would be a mistake to suppose that the Mexicans played the coward that day. They were slain by hundreds in the ranks where they stood when the battle began.

Continuing The Texas Rebellion,

our selection from Houston and His Republic by Charles Edwards Lester published in 1846. The selection is presented in 3 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Texas Rebellion.

Time: 1836

Place: Texas

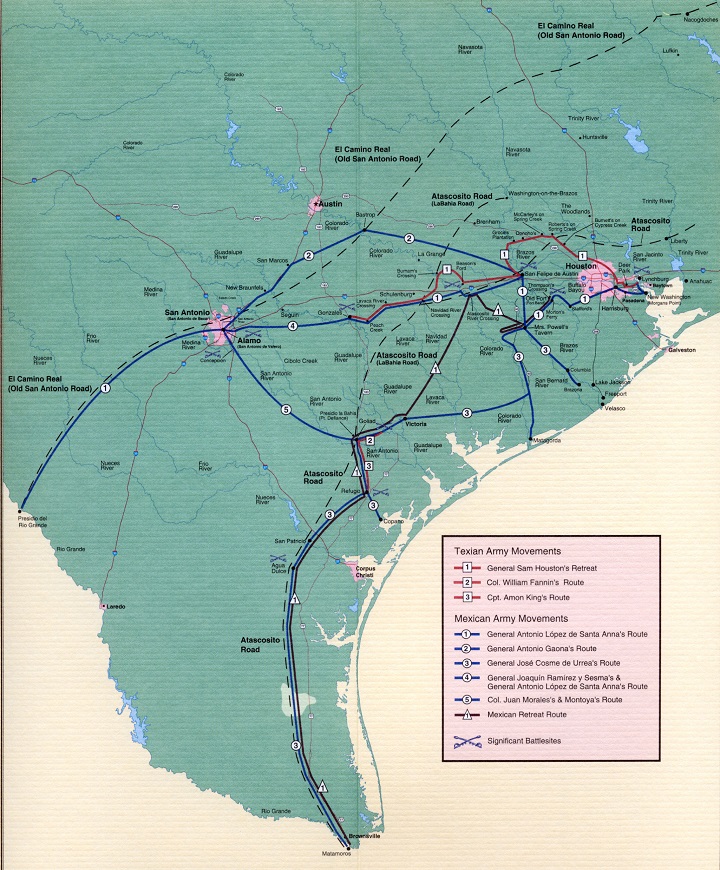

Public domain image from Texas Revolution Maps.

The Texan soldiers rushed on. They were without bayonets, but they converted their rifles into war-clubs and leveled them upon the heads of Santa Anna’s men. Along the breastwork there was little more firing of muskets or rifles — it was a desperate struggle hand to hand. The Texans, when they had broken off their rifles at the breech by smashing the skulls of their enemies, flung them down and drew their pistols. They fired them once, and having no time to reload, hurled them against the heads of their foes, and then, drawing forth their bowie-knives, literally cut their way through the dense masses of the enemy.

It would be a mistake to suppose that the Mexicans played the coward that day. They were slain by hundreds in the ranks where they stood when the battle began, but the fierce and vengeful onslaught of the Texans could not be resisted. They fought as none but freeman can fight when they are striking for their homes, their families, and to revenge their dead kindred. The Mexican officers and men stood firm for a time, but the Texans stamped on them as fast as they fell, and trampled down the prostrate and the dying with the dead, and, clambering over the groaning bleeding mass plunged their knives into the breasts of those in the rear. When the Mexicans saw that the onset of their foe could not be resisted they either attempted to fly and were stabbed in the back, or fell on their knees to plead for mercy, crying, “Me no Alamo! Me no Alamo! Me no Alamo!” These unfortunate slaves of the Mexican tyrant had witnessed that brutal massacre of brave men, and now they could think of no other claim for mercy but the plea they were not there, for they knew the day of vengeance for the Alamo had come at last.

But before the centre breastwork had been carried, the right and left wing of the enemy had been put to the rout or the slaughter. The Mexicans, however, not only stood their ground at first, but made several bold charges upon the Texan lines. A division of their infantry of more than five hundred men made a gallant charge, in handsome order, upon the battalion of Texan infantry. Seeing them hard pressed by a force of three to one, the Commander-in-Chief dashed between them and the enemy’s column, exclaiming, “Come on, my brave fellows, your General leads you ! ” The battalion halted and wheeled into perfect order, like a veteran corps, and Houston gave the order to fire. If the guns of the Texans had all been moved by machinery they could not have been fired more instantaneously. There was a single explosion ; the battalion rushed through the smoke, and those who had not been mowed down by the bullets were felled by smashing blows from the rifle-butts, and the prostrate column was trampled into the mire. Of the five hundred, only thirty-two lived, to surrender as prisoners of war.

In the meantime, although Houston’s wound was bleeding profusely, and his dying horse could scarcely stagger his way over the slain, yet the Commander-in-Chief saw every movement of his army, and followed the tide of battle as it rolled over the field. Wherever his eye fell he saw the Mexicans staggering back under the resistless shock of his heroic soldiers. Regiments and battalions, cavalry and infantry, horses and men were hurled together, and every officer and every man seemed to be bent upon a work of slaughter for himself.

The Mexican army had now been driven from their position, and were flying before their pursuers. Houston saw that the battle was won, and he rode over the field and gave his orders to stop the slaughter of the wounded and of those who surrendered. But it would have been easier to stop the inrolling tide of the sea. He had given “The Alamo” for their war-cry, and the magic word could not be recalled. The ghosts of brave men, massacred at Goliad and the Alamo, flitted through the smoke of battle, and the uplifted hand could not be stayed. “While the battle was in progress,” says General Rusk, “the celebrated Deaf Smith, although on horseback, was fighting with the infantry. When they got near the enemy Smith galloped on ahead, and dashed directly up to the Mexican line. Just as he reached it his horse stumbled and fell, throwing him on his head among the enemy. Having dropped his sword in the fall, he drew one of his pistols from his belt and presented it at the head of a Mexican who was attempting to bayonet him, but it missed fire. Smith then hurled the pistol itself at the head of the Mexican, and, as he staggered back, he seized his gun and began his work of destruction. A young man named Robbins dropped his gun in the confusion of the battle, and happening to run directly in contact with a Mexican soldier who had also lost his musket, the Mexican seized Robbins, and both being stout men, they fell to the ground. Robbins drew his bowie-knife and ended the contest by cutting the Mexican’s throat. On starting out from our camp to begin the attack I saw an old man, named Curtis, carrying two guns. I asked him what reason he had for carrying more than one gun. He answered: ‘Damn the Mexicans; they killed my son and son- in-law in the Alamo, and I intend to kill two of them for it, or be killed myself.’ I saw the old man again during the fight, and he told me he had killed his two men; and ‘if he could find Santa Anna himself he would cut out a razor-strop from his back.'”

Such was the day of vengeance. It was not strange that no invading army, however brave, could long withstand so dreadful an onset. “When the Mexicans were first driven from the point of woods where we encountered them,” continues General Rusk, ” their officers tried to rally them, but the men cried, ‘ It’s no use, it’s no use ; there are a thousand Americans in the woods ! ‘ When Santa Anna saw Almonte’s division running past him he called a drummer and ordered him to beat his drum. The drummer held up his hands and told him he was shot. He called to a trumpeter near him to sound his horn. The trumpeter replied that he also was shot. Just at that instant a ball from one of our cannon struck a man who was standing near Santa Anna, taking off one side of his head. Santa Anna then exclaimed. ‘ Damn these Americans; I believe they will shoot us all!’ He immediately mounted his horse, and commenced his flight.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Sam Houston begins here. Charles Edwards Lester begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.