This series has seven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Defeat at the Alamo.

Introduction

Imagine a football game where one team continually is sacked, fumbles the ball, or else throws passes that are intercepted. Still the other team manages to lose the game. This describes the Texans. The defenders of the Alamo are celebrated for their sacrifice. Militarily one thinks of General Patton’s rule of war: don’t die gloriously for your country; make the other bastard die gloriously for his country. So, how did the Mexicans under Santa Ana lose?

Of the following accounts, that of Houston himself, the Texan’s leader narrates the early steps of the struggle; while Lester, its historian, gives a spirited description of the Battle of San Jacinto, which proved decisive for the success of the movement.

The selections are from:

- a speech by Sam Houston.

- Houston and His Republic by Charles Edwards Lester published in 1846.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. There’s 4 installments by Sam Houston and 3 installments by Charles Edwards Lester. We begin with Sam Houston, speaking in the third person.

Sam Houston was the commander of the Texas forces in the war. He subsequently became Governor of Texas. Charles Lester was a write, a diplomat, and an activist in the abolitionist movement.

Time: 1836

Place: Texas

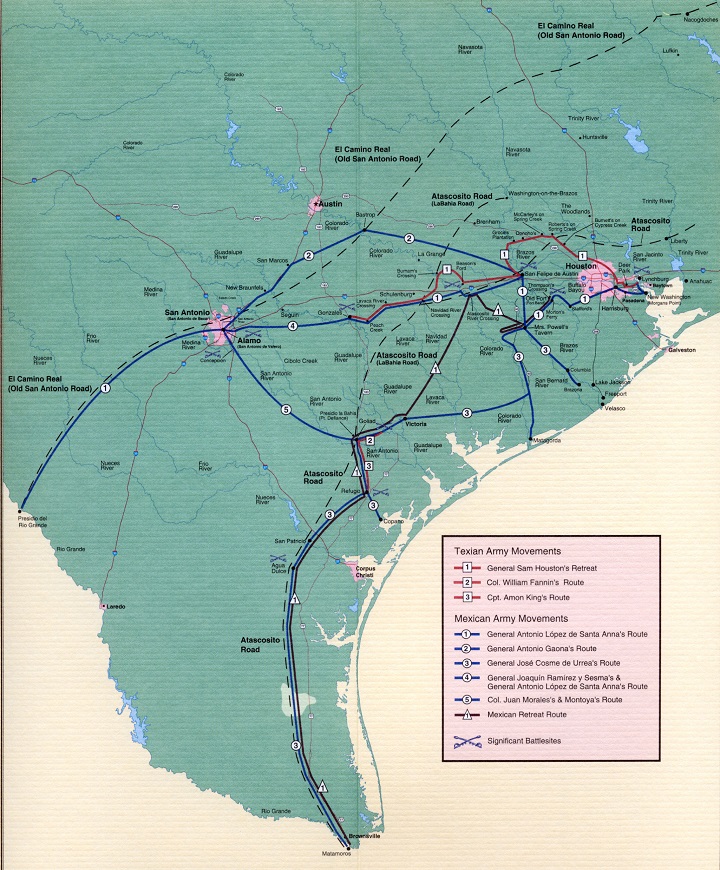

Public domain image from Texas Revolution Maps.

In December, 1835, when the troubles began in Texas, in the inception of its revolution, Houston was appointed major- general of the forces by the consultation then in session at San Felipe. He remained in that command. Delegates, one from each municipality, or what would correspond to counties here, were to constitute the government, with a governor, lieutenant-governor, and council. They had the power of the country. An army was requisite, and means were necessary to sustain the revolution. This was the first organization of anything like a government, which absorbed the power that had previously existed in committees of vigilance and safety in different sections of the country. When the General was appointed, his first act was to organize a force to repel an invading army which he was satisfied would advance upon Texas.

A rendezvous had been established, at which the drilling and organization of the troops were to take place, and officers were sent to their respective posts for the purpose of recruiting men. Colonel Fannin was appointed at Matagorda, to superintend that district, second in command to the General-in-Chief; and he remained there until the gallant band from Alabama and Georgia visited that country. They were volunteers under Colonels Ward, Shackleford, Duvall, and other illustrious names. When they arrived, Colonel Fannin, disregarding the orders of the Commander-in-Chief, became, by countenance of the Council, a candidate for commander of the volunteers. Some four or five hundred of them had arrived, all equipped and disciplined; men of intelligence, men of character, men of chivalry and of honor. A more gallant band never graced the American soil in defense of liberty. He was selected; and the project of the Council was to invade Matamoras, under the auspices of Fannin. San Antonio had been taken in 1835. Troops were to remain there. It was a post more than seventy miles from any colonies or settlements by the Americans. It was a Spanish town or city, with many thousand population, and very few Americans. The Alamo was nothing more than a church, and derived its cognomen from the fact of its being surrounded by poplars or cottonwood trees. The Alamo had been known as a fortress since the Mexican revolution in 1812. The troops remained at Bexar until about the last of December.

The Council, without the knowledge of the Governor, and without the concurrence of the Commander-in-Chief of the army, had secretly sent orders authorizing Grant and others to invade Matamoras, some three hundred miles, I think, through an uninhabited country, and thereby to leave the Alamo in a defenseless position. They marched off, and left only one hundred fifty effective men, taking some two hundred with them. Fannin was to unite with them from the mouth of the Brazos, at Copano, and there the two forces were to unite under the auspices of Colonel Fannin, and were to proceed to Matamoras and take possession of it. The enemy, in the mean time, were known to be advancing upon Texas; and they were thus detaching an inefficient force, which, if it had been concentrated, would have been able to resist all the powers of Mexico combined. The Commander-in-Chief was ordered by the Governor to repair immediately to Goliad, and if the expedition surreptitiously ordered by the Council should proceed to Matamoras, to take charge of it. Under his conduct it was supposed that something might be achieved, or, at least, disaster prevented.

The Council, on January 7th, passed an edict creating Fannin and Johnson military agents, and investing them with all the power of the country, to impress property, receive troops, command them, appoint subordinates throughout the country, and effectually supersede the Commander-in-Chief in his authority. He was ordered to repair to Capano, and did so. While at Goliad he sent an order to Colonel Neill, who was in command of the Alamo, to blow up that place and fall back to Gonzales, making that a defensive position, which was supposed to be the farthest boundary the enemy would ever reach.

This was on January 17th. That order was secretly superseded by the Council; and Colonel W. B. Travis, having relieved Colonel Neill, did not blow up the Alamo and retreat with such articles as were necessary for the defense of the country’; but remained in possession from January 17th until the last of February, when the Alamo was invested by the force of Santa Anna. Surrounded there, and cut off from all succor, the consequence was they were destroyed; they fell victims to the ruthless Santa Anna, by the contrivance of the Council, and in violation of the plans of the Major-General for the defense of the country.[*]

[* The massacre of the Alamo is one of the most memorable tragedies in American military history. Of the men— about one hundred fifty in number — under Colonel Travis in the fort, only one is known to have remained alive, and he escaped before the butchery began. The defend ers had made a desperate resistance during the terrible siege, but not even desperation could enable valor to prevail against the fury of an over whelming force. Among those killed in this slaughter were David Crockett, the famous pioneer, hunter, and politician, and Colonel James Bowie, an American soldier, notorious as a duelist, and as the inventor of the bowie-knife. The feature of extreme atrocity consisted in the murder, by order of Santa Anna, of six men — among them Crockett — who surrendered after the death of their comrades. This outrage rankled in the memory of the men who continued the fight for Texan independence, and, as will be seen below, inspired their vengeful battle-cry.— Ed.]

What was the fate of Johnson, of Ward, and of Morris? They had advanced beyond Capano previous to forming a junction with Fannin, and they were cut off. Fannin subsequently arrived, and attempted to advance, but fell back to Goliad. When the Alamo fell, he was at Goliad. King’s command had been left at Refugio, for the purpose of defending some families, instead of removing them. They were invested there; and Ward, with a battalion of gallant volunteers, was sent to relieve King; but he was annihilated. Fannin was in Goliad. Ward, in attempting to come back, had become lost or bewildered. The Alamo had fallen.

| Master List | Next—> |

Charles Edwards Lester begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.