The two armies were now drawn up in complete order. There were seven hundred Texans on the field, and Santa Anna’s troops numbered over eighteen hundred.

Continuing The Texas Rebellion,

our selection from Houston and His Republic by Charles Edwards Lester published in 1846. The selection is presented in 3 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Charles Lester was a write, a diplomat, and an activist in the abolitionist movement.

Previously in The Texas Rebellion.

Time: 1836

Place: Texas

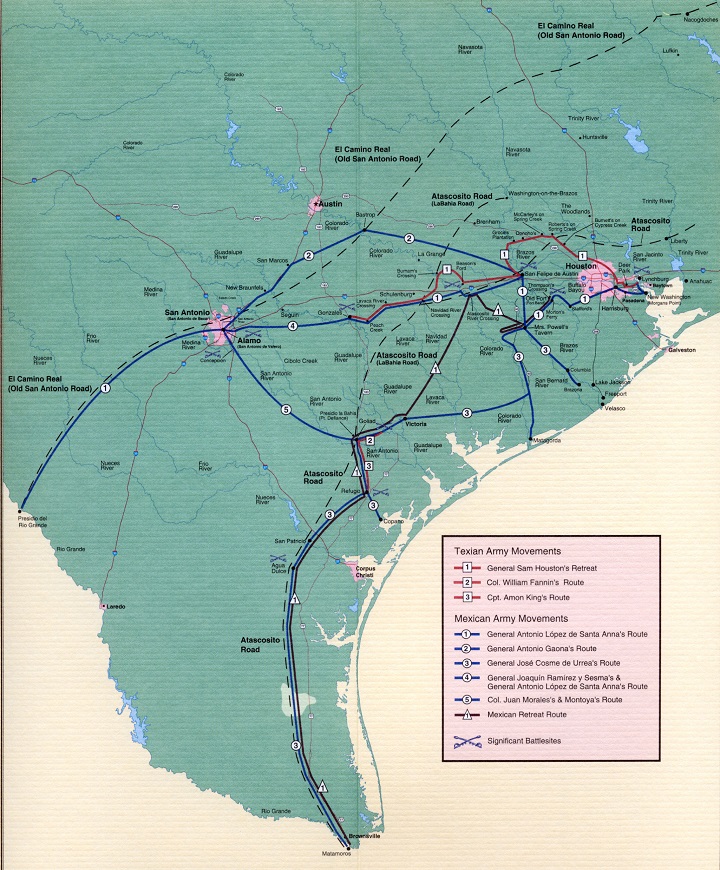

Public domain image from Texas Revolution Maps.

The night that preceded the bloody slaughter of San Jacinto rolled anxiously away, and brightly broke forth the morning of the last day of Texan servitude. Before the first gray streaks shot up in the east, three taps of a drum were heard in the camp, and seven hundred soldiers sprang to their feet as one man. The camp was busy with the soldiers’ hum of preparation for battle, but in the midst of it all Houston slept on calmly and profoundly. The soldiers had eaten the last meal they were to eat till they had won their independence. They were under arms, ready for the struggle.

At last the glorious sun came up over the prairie, without a single cloud. It shone full and clear in the face of the hero, and it waked him to battle. He sprang to his feet and exclaimed, “The sun of Austerlitz has risen again!” His face was calm, and, for the first time in many weeks, every shade of trouble had left his brow. He ordered his commissary-general, Colonel John Forbes, to provide two good axes, and then sent for “Deaf” Smith. He took this faithful and intrepid man aside, and ordered him to conceal the axes in a safe place nearby where he could lay his hands on them at a moment’s warning, and not to pass the b’nes of the sentinels that day without his special orders, nor to be out of his call.

Morning wore away, and about nine o’clock a large body of men were seen moving over a swell of the prairie in the direction of Santa Anna’s camp. They were believed to be a powerful force which had come to join the Mexicans, and the spectacle produced no little excitement in the Texan lines. Houston saw it at a glance, and quelled the apprehension by coolly remarking that “they were the same men they had seen the day before. They had marched round the swell in the prairie and returned in sight of the Texan camp to alarm their foe with the appearance of an immense reinforcement, for it was very evident Santa Anna did not wish to fight. But it was all a ruse de guerre that could be easily seen through — a mere Mexican trick.”

All this did very well, and yet Houston, of course, had quite a different notion on the subject. He sent Deaf Smith and a comrade with confidential orders as spies on their rearward march. They soon returned, and reported publicly that “the General was right — it was all a humbug.” A few minutes after, Deaf Smith whispered quite another story in the private ear of the commander. The enemy they saw was a reinforcement of five hundred forty men, under General Cos, who had heard Santa Anna’s cannon the day before on the Brazos, and come on by forced marches to join his standard. But the secret was kept until it did no harm to reveal it. A proposition was made to the General to construct a floating bridge over Buffalo Bayou, “which might be used in the event of danger.” Houston ordered his adjutant and inspector-generals and an aide to ascertain if the necessary materials could be obtained. They reported that by tearing down a house in the neighborhood they could. “We will postpone it awhile, at all events,” was Houston’s reply.

In the meantime he had ordered Deaf Smith to report to him with a companion well mounted. He retired with them to the spot where the axes had been deposited in the morning. Taking one in either hand and examining them carefully, he handed them to the two trusty fellows, saying: “Now, my friends, take these axes, mount, and make the best of your way to Vince’s Bridge; cut it down and burn it, and come back like eagles or you will be too late for the day.” This was the bridge over which both armies had crossed in their march to the battle-ground of San Jacinto, and it cut off all chance of escape for the vanquished. “This,” said Deaf Smith, in his droll way, “looks a good deal like fight, General.”

The reader will not fail to notice the difference between Houston’s calculations of the results of that day and those of some of his officers. They bethought themselves of building a new bridge — he of cutting down and burning up the only bridge in the neighborhood. The fact was Houston was determined his army should come off victorious that day or leave their bodies on the field.

The day was now wearing away; it was three o’clock in the afternoon, and yet the enemy kept concealed behind his breast works and manifested no disposition to come to an engagement. Events had taken just such a current as Houston expected and desired, and he began to prepare for battle.

In describing his plan of attack we borrow the language of his official report after the battle was over: “The First Regiment, commanded by Colonel Burleson, was assigned the center. The Second Regiment, under the command of Colonel Sherman, formed the left wing of the army. The artillery, under the special command of Colonel George W. Hockley, inspector-general, was placed on the right of the First Regiment, and four companies of infantry, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Millard, sustained the artillery upon the right. Our cavalry, sixty-one in number, commanded by Colonel Mirabeau B. Lamar, placed on our extreme right, completed our line. Our cavalry was first dispatched to the front of the enemy’s left, for the purpose of attracting their notice, while an extensive ‘island’ of timber afforded us an opportunity of concentrating our forces and displaying from that point, agreeably to the previous design of the troops. Every evolution was performed with alacrity, the whole advancing rapidly in line and through an open prairie with out any protection whatever for our men. The artillery advanced and took station within two hundred yards of the enemy’s breast work.”

The two armies were now drawn up in complete order. There were seven hundred Texans on the field, and Santa Anna’s troops numbered over eighteen hundred. Houston had informed Thomas J. Rusk of the plan of the battle, and he approved of it as perfect. The Secretary, it is true, had never been a soldier — he understood little of military evolutions or the discipline of an army — but Houston knew he carried a lion heart in his bosom, and he assigned him the command of the left wing. The General, of course, led the center.

Everything was now ready, and every man at his post waiting for the charge. The two six-pounders had commenced a well- directed fire of grape and canister, and they shattered bones and baggage where they struck — the moment had at last come. Houston ordered the charge and sounded out the war-cry, ” Remember the Alamol ” These magic words struck the ear of every soldier at the same instant, and “The Alamo! The Alamo!” went up from the army in one wild yell which sent terror through the Mexican host. At that moment a rider came up on a horse covered with foam and mire, swinging an axe over his head, and dashed along the Texan lines, crying out, as he had been instructed to do, “I have cut down Vince’s bridge — now fight for your lives and remember the Alamo!” Then the solid phalanx which had been held back for a moment at the announcement, launched forward upon the breastwork like an avalanche of fire. Houston spurred his horse on at the head of the center column right into the face of the foe.

The Mexican army was drawn up in perfect order ready to receive the attack, and when the Texans were within about sixty paces, and before they had fired a rifle, a general flash was seen along the Mexican lines and a storm of bullets went rushing over the Texan army. They fired too high; several balls struck Houston’s horse in the breast, and one ball shattered the General’s ankle. The noble animal staggered for a moment, but Houston spurred him on. If the first discharge of the Mexicans had been well directed, it would have thinned the Texan ranks. But they pressed on, reserving their fire until each man could choose some particular soldier for his target; and before the Mexicans could reload, a murderous discharge of rifle-balls was poured into their ranks.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Sam Houston begins here. Charles Edwards Lester begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

160888 72331There is clearly a great deal to know about this. I believe you made various very good points in attributes also. 880428