The march to Harrisburg was effected through the greatest possible difficulties.

Continuing The Texas Rebellion,

with a selection from a speech by Sam Houston. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Texas Rebellion.

Time: 1836

Place: Texas

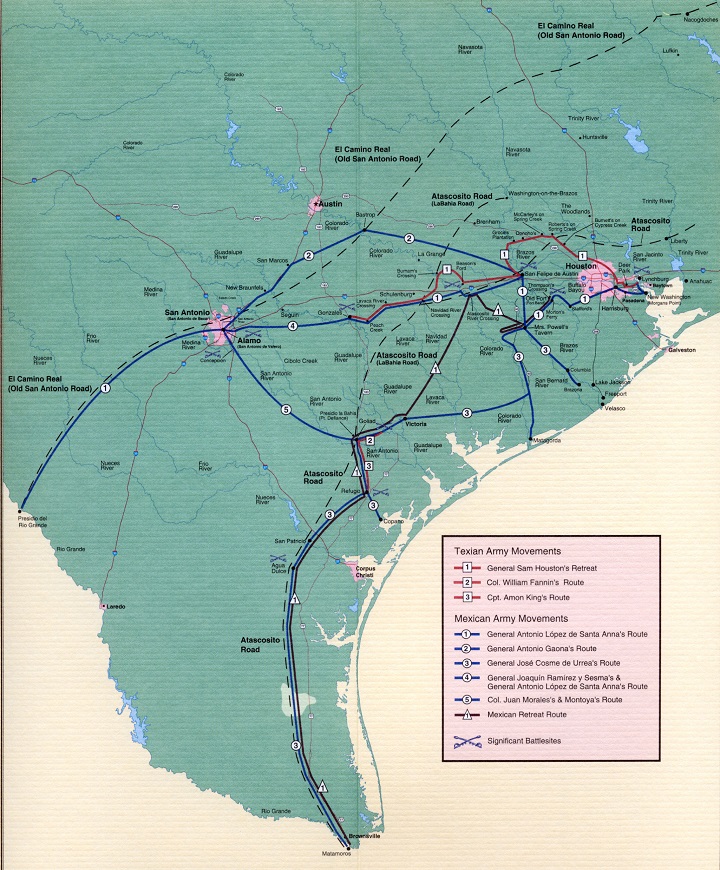

Public domain image from Texas Revolution Maps.

He marched and took position on the Brazos, with as much expedition as was consistent with his situation; but at San Felipe he found a spirit of dissatisfaction in the troops. The Government had removed east. It had left Washington and gone to Harrisburg, and the apprehension of the settlers had been awakened and increased, rather than decreased. The spirits of the men were bowed down. Hope seemed to have departed, and with the little band alone remained anything like a consciousness of strength.

At San Felipe objection was made to marching up the Brazos. It was said that settlements were down below, and persons interested were there. Oxen could not be found for the march, in the morning, of a certain company. The General directed that they should follow as- soon as oxen were collected. He marched up the Brazos, and, crossing Mill Creek, encamped there. An express was sent to him asking his permission for that company to go down the Brazos to Fort Bend, and to remain there. Knowing that it arose from a spirit of sedition, he granted that permission, and they marched down. On the Brazos the efficient force under his command amounted to five hundred twenty men. He remained there from the last of March until April 13th. On his arrival at the Brazos he found that the rains had been excessive. He had no opportunity of operating against the enemy. They marched to San Felipe, within eighteen miles of him, and would have been liable to surprise at any time, had it not been for the high waters of the Brazos, which prevented him from marching upon them by surprise. Thus he was pent up. The portion of the Brazos in which he was became an island. The water had not been so high for years.

On arriving at the Brazos, he found that the Yellowstone, a very respectable steamboat, had gone up the river for the purpose of transporting cotton. She was seized by order of the General, to enable him, if necessary, to pass the Brazos at any moment, and was detained with a guard on board. She remained there for a number of days. The General had taken every precaution possible to prevent the enemy from passing the Brazos below. He had ordered every craft to be destroyed on the river. He knew that the enemy could not have constructed rafts and crossed ; but, by a ruse they obtained the only boat that was in that part of the country, where a command was stationed. They came and spoke English. The boat was sent over, and the Mexicans surprised the boatmen and took possession of it. Those on the east side of the river retreated ; and thus Santa Anna obtained an opportunity of transporting his artillery and army across the Brazos.

The General anticipated that something of the kind must have taken place, because his intelligence from San Felipe was that all was quiet there. The enemy had kept up a cannonade on the position across the river, where over one hundred men were stationed. The encampment on the Brazos was the point at which the first piece of artillery was ever received by the army. They were without munitions ; old horseshoes and all pieces of iron that could be procured had to be cut up; various things were to be provided ; there were no cartridges and but few balls. Two small six-pounders, presented by the magnanimity of the people of Cincinnati, and subsequently called the “Twin Sisters,” were the first pieces of artillery that were used in Texas. From there the march commenced at Donoho’s, three miles from Groce’s. It had required several days to cross the Brazos with the horses and wagons.

The march to Harrisburg was effected through the greatest possible difficulties. The prairies were quagmired. The contents of the wagons had to be carried across the bogs, and the horses attached to empty wagons had to be assisted. No less than eight impediments in one day had to be overcome in that way. Notwithstanding that, the remarkable success of the march brought the army in a little time to Harrisburg, opposite which it halted. “Deaf” Smith (known as such — his proper name was Erasmus Smith), with other spies, had gone over by rafts, and, after crossing, arrested two couriers and brought them into camp. Upon them was found a buckskin wallet containing dispatches of General Filosola to General Santa Anna, as well as from Mexico, and thereby we were satisfied that Santa Anna had marched to San Jacinto with the elite of his army, and we resolved to push on. Orders were given by the General immediately to prepare rations for three days, and to be at an early hour in readiness to cross the bayou. The next morning the Commander-in- Chief addressed a note in pencil to Colonel Henry Raguet, of Nacogdoches, in these words:

“Camp at Harrisburg, April 19, 1836.

“Sir: This morning we are in preparation to meet Santa Anna. It is the only chance of saving Texas. From time to time I have looked for reinforcements in vain. The convention adjourning to Harrisburg struck panic throughout the country. Texas could have started at least four thousand men. We will only have about seven hundred to march with, besides the camp- guard. We go to conquer. It is wisdom, growing out of neces ity, to meet the enemy now; every consideration enforces it. No previous occasion would justify it. The troops are in fine spirits, and now is the time for action.

“We shall use our best efforts to fight the enemy to such advantage as will insure victory, though odds are greatly against us. I leave the result in the hands of a wise God, and rely upon his providence. My country will do justice to those who serve her. The rights for which we fight will be secured, and Texas free.”

A crossing was effected by the evening, and the line of march was taken up. The force amounted to a little over seven hundred men. The camp-guard remained opposite Harrisburg. The cavalry had to swim across the bayou, which is of considerable width and depth. General Rusk remained with the army on the west side. The Commander-in-Chief stepped into the first boat of the pioneers, swam his horse with the boat, and took position on the opposite side, where the enemy were, and continued there until the army crossed. The march was then taken up. A few minutes or perhaps an hour or so of daylight only remained. The troops continued to march until the men became so exhausted and fatigued that they were falling against each other in the ranks, or some falling down.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Sam Houston begins here. Charles Edwards Lester begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.