Though the most gallant spirits were there with him, he remained in the situation all that night and the next day, when a flag of truce was presented; he entered into a capitulation, and was taken to Goliad, on a promise to be returned to the United States with all associated with him.

Continuing The Texas Rebellion,

with a selection from a speech by Sam Houston. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Texas Rebellion.

Time: 1836

Place: Texas

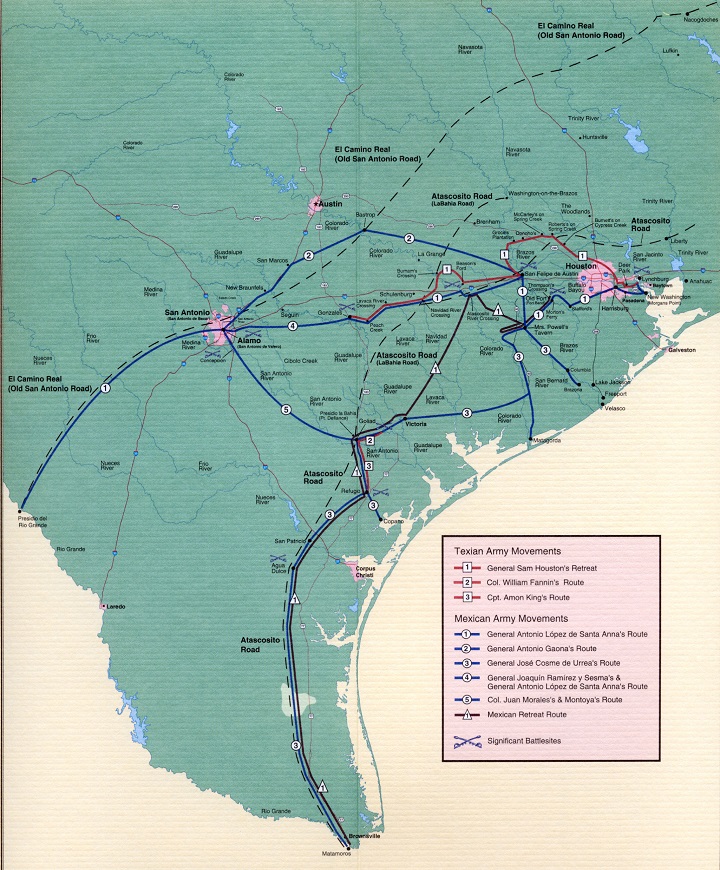

Public domain image from Texas Revolution Maps.

On March 4th the Commander-in-Chief was reelected by the convention, after having laid down his authority. He hesitated for hours before he would accept the situation. He had anticipated every disaster that befell the country, from the detached condition of the troops, under the orders of the Council, and the inevitable destruction that awaited them, and to this effect had so reported to the Governor on February 4th.

When he assumed the command, what was his situation? Had he aid and succor? He had conciliated the Indians by treaty while he was superseded by the unlawful edicts of the Council. He had conciliated thirteen bands of Indians, and they remained amicable throughout the struggle of the revolution. Had they not been conciliated, but turned loose upon our people, the women and children would have perished in their flight arising from panic. After treaty with the Indians, he attended the conventions, and acted in the deliberations of that body, signing the declaration of independence, and was there elected. When he set out for the army, the only hope of Texas remained then at Gonzales.

Men with martial spirit, with well-nerved arms and gallant hearts, had hastily rallied there as the last hope of Texas. The Alamo was known to be in siege. Fannin was known to be embarrassed; Ward, also, and Morris and Johnson, destroyed. All seemed to bespeak calamity of the most direful character. It was under those circumstances that the General started; and what was his escort? A general-in-chief, you would suppose, was at least surrounded by a staff of gallant men. It would be imagined that some prestige ought to be given to him. He was to produce a nation; he was to defend a people; he was to command the resources of the country; and he must give character to the army. He had two aides-de-camp, one captain, and a youth. This was his escort in marching to the headquarters of the ” army,” as it was called. The Provisional Government had become extinct; self-combustion had taken place, and it was utterly consumed.

The General proceeded on his way and met many fugitives. The day on which he left Washington, March 6th, the Alamo had fallen. He anticipated it; and marching to Gonzales as soon as practicable, though his health was infirm, he arrived there on March 11th. He found at Gonzales three hundred seventy- four men, half fed, half clad, and half armed, and without organization. That was the nucleus on which he had to form an army and defend the country. No sooner did he arrive than he sent a dispatch to Colonel Fannin, fifty-eight miles, which would reach him in thirty hours, to fall back. He was satisfied that the Alamo had fallen. Colonel Fannin was ordered to fall back from Goliad twenty-five miles to Victoria, on the Guadalupe, thus placing him within striking distance of Gonzales, for he had only to march twenty-five miles to Victoria to be on the east side of the Colorado, with the only succor hoped for by the General. He received an answer from Colonel Fannin, stating that he had received his order; had held a council of war; and that he had determined to defend the place, and called it Fort Defiance, and had taken the responsibility to disobey the order.

Under these circumstances the confirmation of the fall of the Alamo reached the General. He ordered every wagon but one to be employed in transporting the women and children from the town of Gonzales, and had only four oxen and a single wagon, as he believed, to transport all the baggage and munitions of war belonging to Texas at that point. That was all he had left. He had provided for the women and children; and every female and child left but one, whose husband had just perished in the Alamo; and, disconsolate, she would not consent to leave there until the rear-guard was leaving the place, but invoked the murderous Mexicans to fall upon and destroy her and her children.

Though the news of the fall of the Alamo arrived at eight or nine o’clock at night, that night, by eleven o’clock, the Commander-in-Chief had everything in readiness to march, though panic raged, and frenzy seized upon many; and though it took all his personal influence to resist the panic and bring them to composure, with all the encouragement he could use, he succeeded.

Fannin, after disobeying orders, attempted, on the 19th, to retreat, and had only twenty-five miles to reach Victoria. His opinions of chivalry and honor were such that he would not avail himself of the night to do it in, although he had been admonished by the smoke of the enemies’ encampment for eight days previous to attempt a retreat. He then attempted to retreat in open day. The Mexican cavalry surrounded him. He halted in a prairie, without water; commenced a fortification, and there was surrounded by the enemy, who, from the hill- tops, shot down upon him. Though the most gallant spirits were there with him, he remained in the situation all that night and the next day, when a flag of truce was presented; he entered into a capitulation, and was taken to Goliad, on a promise to be returned to the United States with all associated with him. I believe some few did escape, most of whom came afterward and joined the army.

The General fell back from the Colorado. The artillery had not yet arrived. He had every reason to believe that the check given to General Sesma, opposite to his camp on the west side of the Colorado, would induce him to send for reinforcements, and that Fannin having been massacred, a concentration of the enemy would necessarily take place, and that an overwhelming force would soon be upon him. He knew that one battle must be decisive of the fate of Texas. If he fought a battle and many of his men were wounded, he could not transport them, and he would be compelled to sacrifice the army to the wounded. He determined to fall back, and did so, and on falling back received an accession of three companies that had been ordered from the mouth of the Brazos.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Sam Houston begins here. Charles Edwards Lester begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.