When the certain news of Lincoln’s election finally came, it was hailed with joy and acclamation by both the leaders and the people of South Carolina. They had at length their much coveted pretext for disunion.

Continuing South Secedes from the United States,

with a selection from Abraham Lincoln, A History by John Hay and by John Nicolay published in 1890. This selection are presented in 4.5 installments for 5 minute daily reading.

Previously in South Secedes from the United States.

Time: 1860

Place: Southern United States

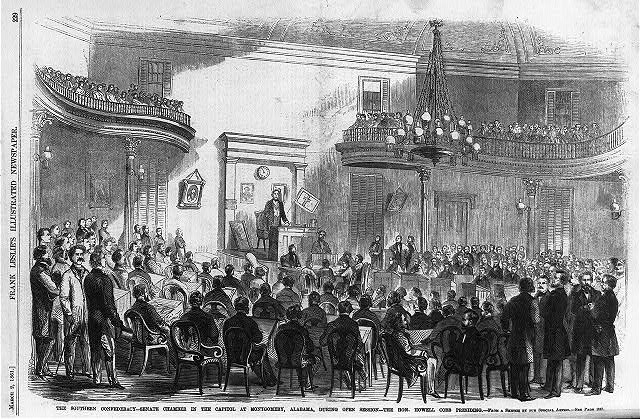

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

As to the alleged destruction of equality, the North proposed to deny to the slave-States no single right claimed by the free-States. The talk about “provinces of a consolidated despotism to be governed by a fixed majority” was, in itself an absurd contradiction in terms, which repudiated the fundamental idea of republican government. The acknowledgment that any danger from anti-slavery “measures” was only in the future, negatived its validity as a present grievance. Hostility to “our institutions” was expressly disavowed by full constitutional recognition of slavery under State authority. The charge of “sectionalism” came with a bad grace from a State whose newspapers boasted that none but the Breckinridge ticket was tolerated within her borders, and whose elsewhere obsolete “institution” of choosing Presidential electors by the Legislature instead of by the people, combined with such a dwarfed and crippled public sentiment, made it practically impossible for a single vote to be cast for either Lincoln or Douglas or Bell — a condition mathematically four times as “sectional” as that of any State of the North.

Finally, the avowed determination to secede because a Presidential election was about to be legally gained by one of the three opposing parties, after she had freely and fully joined in the contest, was an indulgence of caprice utterly incompatible with any form of government whatever.

There is no need here to enter upon a discussion of the many causes which, had given to the public opinion of South Carolina so radical and determined a tone in favor of disunion. Maintaining persistence, and gradually gathering strength almost continuously since the nullification furor of 1832, it had become something more than a sentiment among its devotees: it had grown into a species of cult or party religion, for the existence of which no better reason can be assigned than that it sprang from a blind hero-worship locally accorded to John C. Calhoun, one of the prominent figures of American political history. As representative in Congress, Secretary of War under President Monroe, Vice-President of the United States under President John Quincy Adams, for many years United States Senator from South Carolina, and the radical champion of States Rights, Nullification, and Slavery, his brilliant fame was the pride, but his false theories became the ruin, of his State and section.

[South Carolina “House Journal,” Called Session, 1860, pp. 16, 17.]

Governor Gist and his secession coadjutors had evidently still a lingering hope that the election might by some unforeseen contingency result in the choice of Breckinridge. On no other hypothesis can we account for the fact that on the 6th of November, when Northern ballots were falling in such an ample shower for Lincoln, the South Carolina Legislature, with due decorum and statute regularity, appointed Presidential electors for the State, and formally instructed them to vote for Breckinridge and Lane. The dawn of November 7 dispelled these hopes. The “strong probability” had become a stubborn fact.

When the certain news of Lincoln’s election finally came, it was hailed with joy and acclamation by both the leaders and the people of South Carolina. They had at length their much coveted pretext for disunion; and they now put into the enterprise a degree of earnestness, frankness, courage, and persistency worthy of a better cause. Public opinion, so long prepared, responded with enthusiasm to the plans and calls of the leaders. Manifestations of disloyalty became universal. Political clubs were transformed into military companies. Drill-rooms and armories were alive with nightly meetings. Sermons, agricultural addresses, and speeches at railroad banquets were only so many secession harangues. The State became filled with volunteer organizations of “minute men.”

The Legislature, remaining in extra session, and cheered and urged on by repeated popular demonstrations and the inflamed speeches of the highest State officials, proceeded without delay to carry out the Governor’s program. In fact, the members needed no great incitement. They had been freshly chosen within the preceding month; many of them on the well-understood “resistance” issue. Their election took place on the 8th and 9th days of October, 1860. Since there was but one party in South Carolina, there could be no party drill; but a tyrannical and intolerant public sentiment usurped its place and functions. On the sixteen different tickets paraded in one of the Charleston newspapers, the names of the most pronounced disunionists were the most frequent and conspicuous. “Southern rights at all hazards,” was the substance of many mottoes, and the palmetto and the rattlesnake were favorite emblems. There was neither mistaking nor avoiding the strong undercurrent of treason and rebellion here manifested, and the Governor’s proclamation had doubtless been largely based upon it.

[South Carolina, “House Journal,” Called Session, 1860, pp. 13, 14.]

The first day’s session of the Legislature (November 5) developed one of the important preparatory steps of the long-expected revolution. The Legislature of 1859 had appropriated a military contingent fund of one hundred thousand dollars, “to be drawn and accounted for as directed by the Legislature.” The appropriation had been allowed to remain untouched. It was now proposed to place this sum at the control of the Governor to be expended in obtaining improved small arms, in purchasing a field battery of rifled cannon, in providing accouterments, and in furnishing an additional supply of tents; and a resolution to that effect was passed two days later, The chief measure of the session, however, was a bill to provide for calling the proposed State Convention, which it was well understood would adopt an ordinance of secession. There was scarcely a ripple of opposition to this measure. One or two members still pleaded for delay, to secure the cooperation of Georgia, but dared not record a vote against the prevailing mania. The chairman of the proper committee on November 10 reported an act calling a convention “for the purpose of taking into consideration the dangers incident to the position of the State in the Federal Union,” which unanimously became a law November 13, and the extra session adjourned to meet again in regular annual session on the 26th.

Meanwhile public excitement had been kept at fever heat by all manner of popular demonstrations. The two United States Senators and the principal Federal officials resigned their offices with a public flourish of their insubordinate zeal. An enthusiastic ratification meeting was given to the returning members of the Legislature. To give still further emphasis to the general movement a grand mass meeting was held at Charleston on the 17th of November. The streets were filled with the excited multitude. Gaily dressed ladies crowded balconies and windows, and zealous mothers decorated their children with revolutionary badges. There was a brisk trade in fire-arms and gunpowder. The leading merchants and prominent men of the city came forth and seated themselves on platforms to witness and countenance a formal ceremony of insurrection. A white flag, bearing a palmetto tree and the legend Animis opibusque parati (one of the mottoes on the State seal), was, after solemn prayer, displayed from a pole of Carolina pine. Music, salutes, and huzzahs filled the air. Speeches were addressed to “citizens of the Southern Republic.” Orations and processions completed the day, and illuminations and bonfires occupied the night. The preparations were without stint. The proceedings and ceremonies were conducted with spirit and abandon. The rejoicings were deep and earnest. And yet there was a skeleton at the feast; the Federal flag, invisible among the city banners, and absent from the gay bunting and decorations of the harbor shipping, still floated far down the bay over a faithful commander and loyal garrison in Fort Moultrie.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Jefferson Davis begins here John Hay and John Nicolay’s begins here. Abraham Lincoln begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.