Few, if any, then doubted the right of a State to withdraw its grants delegated to the Federal Government, or, in other words, to secede from the Union.

Continuing South Secedes from the United States,

with a selection from Davis’s Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government by Jefferson Davis published in 1881. This selection is presented in 4.5 installments for 5 minute reading.

Previously in South Secedes from the United States.

Time: 1860

Place: Southern United States

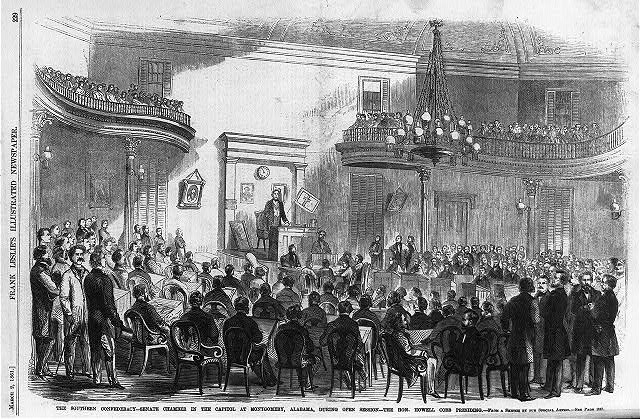

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It needed but little knowledge of the status of parties in the several States to foresee a probable defeat if the conservatives were to continue divided into three parts, and the aggressives were to be held in solid column. But angry passions, which are always bad counselors, had been aroused, and hopes were still cherished, which proved to be illusory. The result was the election, by a minority, of a President whose avowed principles were necessarily fatal to the harmony of the Union.

Of 303 electoral votes, Lincoln received 180; but of the popular suffrage of 4,676,8 5 3 votes, which the electors represented, he obtained only 1,866,352, something over a third of the votes. This discrepancy was owing to the system of voting by “general ticket”—that is, casting the State votes as a unit, whether unanimous or nearly equally divided. Thus, in New York, the total popular vote was 675,156, of which 362,646 were cast for the so called Republican (or Lincoln) electors, and 312,510 against them. New York was entitled to 35 electoral votes. Divided on the basis of the popular vote, 19 of these would have been cast for Lincoln, and 16 against him. But under the “general ticket” system the entire 35 votes were cast for the Republican candidates, thus giving them not only the full strength of the majority in their favor, but that of the great minority against them super added. So of other Northern States, in which the small majorities on one side operated with the weight of entire unanimity, while the virtual unanimity of the Southern States counted nothing more than a mere majority would have done.

The manifestations which followed this result, in the Southern States, did not proceed, as has been unjustly charged, from chagrin at their defeat in the election, or from any personal hostility to the President — elect, but from the fact that they recognized in him the representative of a party professing principles destructive to “their peace, their prosperity, and their domestic tranquility.” The long — suppressed fire burst into frequent flame, but it was still controlled by that love of the Union which the South had illustrated on every battlefield from Boston to New Orleans. Still it was hoped, against hope, that some adjustment might be made to avert the calamities of a practical application of the theory of an “irrepressible conflict.”

Few, if any, then doubted the right of a State to withdraw its grants delegated to the Federal Government, or, in other words, to secede from the Union; but in the South this was generally regarded as the remedy of last resort, to be applied only when ruin or dishonor was the alternative. No rash or revolutionary action was taken by the Southern States, but the measures adopted were considerate, and executed advisedly and deliberately. The Presidential election occurred (as far as the popular vote, which determined the result, was concerned) in November, 1860. Most of the State Legislatures convened soon afterward in regular session. In some cases special sessions were convoked for the purpose of calling State conventions—the recognized representatives of the sovereign will of the people—to be elected expressly for the purpose of taking such action as should be considered needful and proper under the existing circumstances.

These conventions, as it was always held and understood, possessed all the power of the people assembled in mass; and therefore it was conceded that they, and they only, could take action for the withdrawal of a State from the Union. The con sent of the respective States to the formation of the Union had been given through such conventions, and it was only by the same authority that it could properly be revoked. The time required for this deliberate and formal process precludes the idea of hasty or passionate action, and none who admit the primary power of the people to govern themselves can consistently deny its validity and binding obligation upon every citizen of the several States. Not only was there ample time for calm consideration among the people of the South, but for due reflection by the General Government and the people of the Northern States.

President Buchanan was in the last year of his Administration. His freedom from sectional asperity, his long life in the public service, and his peace — loving and conciliatory character were all guarantees against his precipitating a conflict between the Federal Government and any of the States; but the feeble power that he possessed in the closing months of his term to mould the policy of the future was painfully evident. Like all who had intelligently and impartially studied the history of the formation of the Constitution, he held that the Federal Government had no rightful power to coerce a State. Like the sages and patriots who had preceded him in the high office that he filled, he believed that “Our Union rests upon public opinion, and can never be cemented by the blood of its citizens shed in civil war. If it can not live in the affections of the people, it must one day perish. Congress may possess many means of preserving it by conciliation, but the sword was not placed in its hand to preserve it by force.” (Message of December 3, 1860.)

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Jefferson Davis begins here John Hay and John Nicolay’s begins here. Abraham Lincoln begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.