Today’s installment concludes The Beginning of British Power in India,

our selection from Ledger and Sword: Or, The honourable company of merchants of England trading to the East Indies, 1599-1874 by Henry Beckles Willson published in 1903.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Beginning of British Power in India.

Time: 1612

Place: India

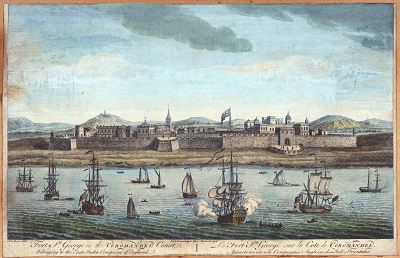

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The various inconveniences to the company from the separate classes of adventurers being enabled to fit out equipments on their own particular portions of stock, finally evoked a change in the constitution of the company. In 1612 it was resolved that in future the trade should be carried on by means of a joint stock only, and on the basis of this resolution the then prodigious sum of four hundred twenty-nine thousand pounds was subscribed. Although portions of this capital were applied to the fitting out of four voyages, the general instructions to the commanders were given in the name and by the authority of the governor, deputy governor, and committees of the Company of Merchants of London trading to the East Indies.

The whole commerce of the company was now a joint concern, and the embarrassing principle of trading on separate ventures came to an end. Experience had amply demonstrated that detached equipments exposed the whole trade to danger in the East, in their efforts to establish trade. The first twelve voyages were, therefore, regarded in the light of an experiment to establish a solid commerce between England and India.

Upon such terms the period known as the first joint stock was entered upon, which comprised four voyages between the years 1613 and 1616. The purchase, repair, and equipment of vessels during these four years amounted to two hundred seventy-two thousand five hundred forty-four pounds, which, with the stock and cargoes, made up the total sum raised among the members at the beginning of the period, viz., four hundred twenty-nine thousand pounds.

Under this new system Captain Downton was given command of the fleet, in the company’s merchantmen, the New Year’s Gift, thus named because it had been launched on January 1st–an armed ship of five hundred fifty tons–and three other vessels. Downton went equipped with legal as well as military implements. King James made him master of the lives of the crews, and empowered him to use martial law in cases of insubordination.

“We are not ignorant,” said the monarch, in the royal commission which he vouchsafed to the company’s commander, “of the emulation and envy which doth accompany the discovery of countries and trade, and of the quarrels and contentions which do many times fall out between the subjects of divers princes when they meet the one with the other in foreign and far remote countries in prosecuting the course of their discoveries.” Consequently Captain Downton was warned not to stir up bad blood among the nations, but if he should be by the company’s rivals unjustly provoked he was at liberty to retaliate, but not to keep to himself any spoils he might take, which were to be rendered account of, as by ancient usage, to the King.

Before Downton could reach his destination, the chief energies of the company’s agents in India appear to have been bent upon forming a series of exchanges between the west coast and the factory at Bantam. The little band of servants at the new factory at Surat, headed by the redoubtable Aldworth, gave it as their opinion not only that sales of English goods could be effected at this port, but that they might be pushed to the inland markets and the adjoining seaports. Aldworth stated that in his journey to Ahmedabad he had passed through the cities of Baroche and Baroda, and had discovered that cotton, yarn and “baftees” could be bought cheaper from the manufacturers in that country than at Surat. At Ahmedabad he was able to buy indigo at a low rate, but in order to establish such a trade capital of from twelve to fifteen thousand pounds was required to be constantly in the hands of the factor. It was thought at Surat that it would be expedient to fix a resident at the Mogul’s court at Agra to solicit the protection of that monarch and his ministers.

Downton arrived at Surat, October 15, 1614, to find the attitude of the Portuguese toward the English more than ever hostile. At the same time trouble impended between the Portuguese and the Nawab of Surat. In order to demolish all opposition at one blow, the former collected their total naval force at Goa for a descent upon both natives and new-comers at Surat. Their force consisted of six large galleons, several smaller vessels, and sixty native barges, or “frigates” as they were called, the whole carrying a hundred thirty-four guns and manned by twenty-six hundred Europeans and six thousand natives. To meet this fleet, Downton had but his four ships, and three or four Indian-built vessels called “galivats,” manned altogether with less than six hundred men. The appearance of the Portuguese was the signal for fright and submission on the part of the Nawab; but his suit was contemptuously spurned by the Viceroy of Goa, who, on January 20th, advanced upon the company’s little fleet. He did not attempt to force the northern entrance of Swally Hole, where the English lay, which would have necessitated an approach singly, but sent on a squadron of the native “frigates” to cross the shoal, surround and attack the Hope, the smallest of the English ships, and board her. But in this they were foiled after a severe conflict. Numbers of the boarders were slain and drowned, and their frigates burned to the water’s edge. Again and again during the ensuing three weeks did the Portuguese make efforts to dislodge the English; but the dangerous fire-ships they launched were evaded by night and their onslaught repulsed by day, and so at length, with a loss of five hundred men, the Portuguese viceroy, on February 13th, withdrew.

His withdrawal marked a triumph for the company’s men. Downton was received in state by the overjoyed Nawab, who presented him with his own sword, “the hilt of massive gold, and in lieu thereof,” says Downton, “I returned him my suit, being sword, dagger, girdle, and hangers, by me much esteemed of, and which made a great deal better show, though of less value.”

A week later Downton set out with his great fleet for Bantam. Just off the coast the enemy’s fleet was again sighted approaching from the west. For three days the English were in momentary apprehension of an attack, but the Viceroy thought better of it, and on the 6th “bore up with the shore and gave over the hopes of their fortunes by further following of us.”

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Beginning of British Power in India by Henry Beckles Willson from his book Ledger and Sword: Or, The honourable company of merchants of England trading to the East Indies, 1599-1874 published in 1903. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Beginning of British Power in India here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.