A caucus of prominent South Carolina leaders is said to have been held on October 25, at the residence of Senator Hammond.

Continuing South Secedes from the United States,

with a selection from Abraham Lincoln, A History by John Hay and by John Nicolay published in 1890. This selection are presented in 4.5 installments for 5 minute daily reading.

Previously in South Secedes from the United States.

Time: 1860

Place: Southern United States

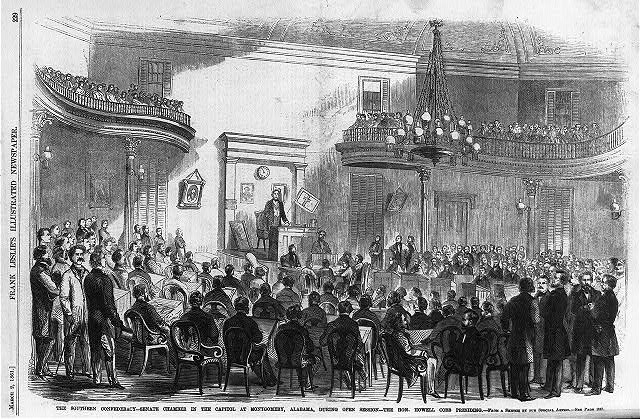

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Jefferson Davis’ selection, conclusion

While engaged in the consultation with the Governor, just referred to, a telegraphic message was handed to me from two members of President Buchanan’s Cabinet, urging me to proceed “immediately” to Washington. This dispatch was laid before the Governor and the members of Congress from the State who were in conference with him, and it was decided that I should comply with the summons. I was afterward informed that my associates considered me “too slow,” and they were probably correct in the belief that I was behind the general opinion of the people of the State as to the propriety of prompt secession.

On arrival at Washington I found, as had been anticipated, that my presence there was desired on account of the influence which it was supposed I might exercise with the President in relation to his forthcoming message to Congress. On paying my respects to the President, he told me that he had finished the rough draft of his message, but that it was still open to revision and amendment, and that he would like to read it to me. He did so, and very kindly accepted all the modifications which I suggested. The message was afterward somewhat changed, and, with great deference to the wisdom and statesmanship of its author, I must say that, in my judgment, the last alterations were unfortunate — so much so, that when it was read in the Senate I was reluctantly constrained to criticize it. Compared, however, with documents of the same class which have since been addressed to the Congress of the United States, the reader of Presidential messages must regret that it was not accepted by President Buchanan’s successors as a model, and that his views of the Constitution had not been adopted as a guide in the subsequent action of the Federal Government.

The popular movement in the South was tending steadily and rapidly toward the secession of those known as “planting States”; yet, when Congress assembled on December 3, 1860, the representatives of the people of all those States took their seats in the House, and they were all represented in the Senate, except South Carolina, whose Senators had tendered their resignation to the Governor immediately on the announcement of the result of the Presidential election. Hopes were still cherished that the Northern leaders would appreciate the impending peril; would cease to treat the warnings, so often given, as idle threats; would refrain from the bravado, so often and so unwisely indulged, of ability “to whip the South” in thirty, sixty, or ninety days; and would address themselves to the more manly purpose of devising means to allay the indignation and quiet the apprehensions, whether well founded or not, of their Southern brethren. But the de bates of that session manifest, on the contrary, the arrogance of a triumphant party, and the determination to reap to the uttermost the full harvest of a party victory.

by John George Nicolay and John Hay

The secret circular of Governor Gist, of South Carolina, heretofore quoted, inaugurated the great American Rebellion a full month before a single ballot had been cast for Abraham Lincoln. This was but repeating in a bolder form the action taken by Governor Wise, of Virginia, during the Frémont campaign four years before. But, instead, as in that case, of confining himself to a proposed consultation among slave-State executives, Governor Gist proceeded almost immediately to a public and official revolutionary act.

On the 12th of October, 1860, he issued his proclamation convening the Legislature of South Carolina in extra session, “to appoint electors of President and Vice-President … and also that they may, if advisable, take action for the safety and protection of the State.” There was no external peril menacing either the commonwealth or its humblest citizen; but the significance of the phrase was soon apparent.

[South Carolina “House Journal,” Called Session, 1860, pp. 10, 11.]

A caucus of prominent South Carolina leaders is said to have been held on October 25, at the residence of Senator Hammond. Their deliberations remained secret, but the determination arrived at appears clearly enough in the official action of Governor Gist, who was present, and who doubtless carried out the plans of the assemblage. When the Legislature met on November 5 (the day before the Presidential election) the Governor sent them his opening message, advocating both secession and insurrection, in direct and undisguised language. He recommended that in the event of Lincoln’s election, a convention should be immediately called; that the State should secede from the Federal Union; and “if in the exercise of arbitrary power and forgetful of the lessons of history, the Government of the United States should attempt coercion, it will be our solemn duty to meet force by force.” To this end he recommended a reorganization of the militia and the raising and drilling an army of ten thousand volunteers. He placed the prospects of such a revolution in a most hopeful and encouraging light. “The indications from many of the Southern States,” said he, “justify the conclusion that the secession of South Carolina will be immediately followed, if not adopted simultaneously, by them, and ultimately by the entire South. The long-desired cooperation of the other States having similar institutions, for which the State has been waiting, seems to be near at hand; and, if we are true to ourselves, will soon be realized.”

Governor Gist’s justification of this movement as attempted was (in his own language) “the strong probability of the election to the Presidency of a sectional candidate by a party committed to the support of measures, which if carried out will inevitably destroy our equality in the Union, and ultimately reduce the Southern States to mere provinces of a consolidated despotism to be governed by a fixed majority in Congress hostile to our institutions.”

This campaign declamation, used throughout the whole South with great skill and success, to “fire the Southern heart,” was wholly defective as a serious argument.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Jefferson Davis begins here John Hay and John Nicolay’s begins here. Abraham Lincoln begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.