This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: First Voyages of the British East India Company.

Introduction

After the Portuguese discovery of the passage round Africa, toward the end of the fifteenth century, other European nations for some time appeared to recognize Portugal’s exclusive claim to the navigation of that route. In 1510 the Portuguese made a permanent settlement in India at Goa. But during this century the Dutch obtained a foothold in the country, and in 1580 Portugal was conquered by Spain.

Dutch enterprise and the Spanish absorption of Portugal’s Indian establishments aroused the commercial spirit of England. In 1599 an English association was formed, with a large fund, “for trade to the East Indies.” In December, 1600, Queen Elizabeth granted this association a charter, incorporating the “Adventurers” under the title of “the Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies.” The company was allowed unlimited rights of purchasing lands, and a fifteen years’ monopoly of trade.

By chartering the original English East India Company, Queen Elizabeth took the first step toward establishing the British. It began English trade with India, and its operations prepared the way for British government in that vast country.

In 1609 the charter was renewed and made perpetual by James I; but at first the company appears to have done no very extensive business. The beginning of its more active career, in the midst of grave difficulties and conflicts, is well described by Willson, whose history thus covers an important period in the development of India and in the expansion of British power.

This selection is from Ledger and Sword: Or, The honourable company of merchants of England trading to the East Indies, 1599-1874 by Henry Beckles Willson published in 1903. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Henry Beckles Willson, known as “Beckles Willson”, (26 August 1869, Montreal – 1942) was a Canadian journalist, WW I soldier, historian and prolific author.

Time: 1612

Place: India

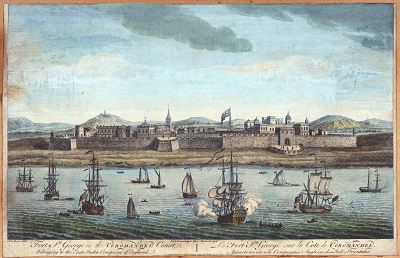

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

When the East India Company had been in existence eleven years it possessed hardly more than the rudiments of factories in the Indies, while the Dutch boasted fully a dozen regularly established trading-settlements, from most of which they had ejected the Spaniards and Portuguese.

France, no longer restrained by Spain and the Pope, naturally looked jealously on these efforts of Englishmen and Dutchmen to exploit the East to their own advantage. In 1609 we learn that the subjects of Henry IV, “who had long aspired to make themselves strong by sea,” took the opportunity of a treaty made between James I and the French King to “set on foot this invention, a society to trade into the East Indies,” with a capital of four million crowns. Becher, the English ambassador at Paris, wrote in 1609 to Lord Salisbury that Dutch seamen were being “engaged at great pay and many of their ships bought.” The States-General strongly remonstrated against this proceeding, and threatened to “board the French ships wherever they found them, and hang all Flemings found in them.” This threat appears to have been effectual, and the project was abandoned. A little later, in 1614, the French again projected taking part in the East India trade, and accounts were current in London concerning ships and patents from King Louis, but this, too, ended lamely and nothing practical was effected for full half a century.

The company always had before it the danger of attack by Spanish or Portuguese, and its captains and agents were put perpetually on their guard. But it never seems to have occurred to the court of committees that there was any danger to be apprehended from the Dutch, so that they were all the more astonished and chagrined at the failure to establish trade with the Moluccas, where the natives were so friendly to the English and offered them every facility, but, owing to Dutch oppression, in vain.

In the first voyage James Lancaster had established factories at Achin and Bantam. In the second voyage Sir Henry Middleton was instructed to endeavor to found a factory on the island of Banda. He carried on some trade, but neither he nor his successor in the third voyage, Captain Keeling, was able to override the opposition of the Dutch and secure a foothold. In the instructions issued to the last-named he was requested to establish, if possible, a factory at Aden, from whence he was to proceed to the Gulf of Cambay, seeking a good harbor there “for the maintenance of a trade in those parts hereafter in safety from the danger of the Portuguese, or other enemies, endeavoring also to learn whether the King of Cambay or Surat, or any of his havens, be in subjection to the Portuguese–and what havens of his are not?–together with the dangers and depths of the water, there for passage, that by this certain notice and diligent inquiry–which we wish to be set down in writing for the company’s better information–whereby we may hereafter attempt further trade there, or otherwise desist.”

In no fighting mood, therefore, was the company — whatever their servants’ views — but prudently inclined to keep out of the way of the once terrible and still dreaded Portuguese. In vain, as we have seen, did Captain Hawkins exert himself to obtain concessions from the Grand Mogul which would survive the displeasure of his European rivals, who had by their ships, arms, and intrigues completely terrified the governors and petty rajahs of the coast.

In 1611 Anthony Hippon, in the Globe, sailed for the Coromandel (or Madras) coast with the object of setting a factory, if possible, at Pulicat, and sharing in the port-to-port trade which the Dutch had lately built up there. The idea seems to have originated with a couple of Dutchmen, named Floris and Antheunis, formerly in the Dutch service, who were charged with the management of the business. So far as Pulicat was concerned, the scheme failed, but the captain of the Globe, resolved to land his factory somewhere, lit upon Pettapoli, farther up the coast, where he arrived on August 18, 1611. This was the company’s first settlement in the Bay of Bengal. But although the reception from the local governor and the King of Golconda was friendly, yet the place proved to be a deadly swamp and the trade was small.

When the landing of certain factors and merchandise had thus taken place at Pettapoli, Captain Hippon set sail farther northward to the ancient port of Masulipatam, which, forming “a coveted roadstead on the open coast line of Madras,” was destined to be the theatre of much truculent rivalry between the European traders on the Coromandel coast. Here, on the last day of August, Hippon and Floris landed, and a factory was set up. A cargo of calicoes was duly obtained, whereupon the Globe departed for Bantam and the Far East to seek spices and pepper in exchange. Such were the beginnings of English trade on the east of the Indian peninsula. Two years later the company’s servants received from the Hindu King of Vitayanagar a firman to build a fort, written on a leaf of gold–a document which was preserved at Madras until its capture by the French in the next century.

Following hard upon their summary dismissal from Surat, Middleton, Hawkins, and the rest, disinclined for their masters’ sake to come to close quarters with the Dutch in the Spice Islands, directed their views to the establishment of a factory at Dabul. In this likewise they failed. In despair at not procuring a cargo, they went in for piracy and fierce retaliation upon the Turkish authorities for their treatment of them in the Red Sea. A couple of vessels hailing from Cochin were captured, and some cloves, cinnamon, wax, bales of china silk, and rice were taken out of them and removed to the ship Trade’s Increase.

In the midst of a lively blockade of the Red Sea ports they were joined by Captain John Saris, with four ships, belonging to the company’s eighth voyage, who agreed to lend his forces for whatever the combined fleets undertook, if granted a third of the profits for the benefit of his particular set of subscribers. All this anomalous confusion between the various interests within the same body corporate could have but one issue. The rival commanders took to quarrelling over the disposition of the hundred thousand pieces-of-eight which Middleton hoped to squeeze out of the Governor of Mocha for outrages upon the English fleet. Strife ran high between them, and in the end Saris in the Clove and Towerson in the Hector sailed away from the Red Sea, leaving Middleton and Downton to settle matters on their own account.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.