Introducing South Secedes from the United States,

serialized in nine total installments for 5 minute reading.

How did the United States first split apart? The story of the secession of the southern states is here told by personages who were central to it. Jefferson Davis was the President of the Confederacy. John Hay and John Nicolay were beside Lincoln during the campaign, accompanied him to Washington and formed his inner staff during the war. We conclude this series with Lincoln himself — first inaugural address.

The selections are from:

- Davis’s Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government by Jefferson Davis published in 1881.

- John Hay and by John Nicolay published in 1890.

- Inaugural Speech by Abraham Lincoln published in 1861.

Summary of daily installments:

| Jefferson Davis’s installments: | 4.5 |

| John Hay and John Nicolay’s installments: | 1.5 |

| Abraham Lincoln’s installments: | 3 |

| Total installments: | 9 |

We begin with Jefferson Davis.

Time: 1860

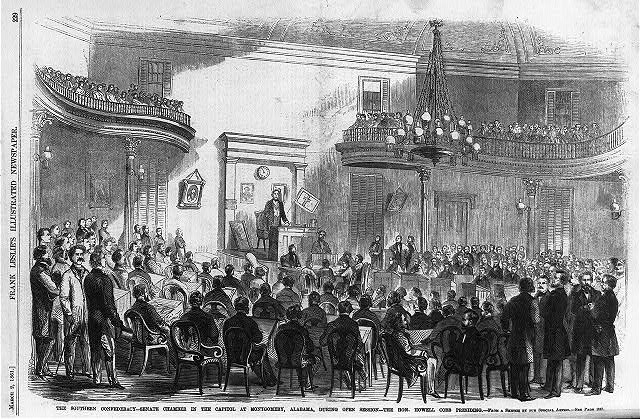

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

When, at the close of the War of the Revolution, each of the thirteen colonies that had been engaged in that contest was severally acknowledged by the mother — country, Great Britain, to be a free and independent State, the confederation of those States embraced an area so extensive, with climate and products so various, that rivalries and conflicts of interest soon began to be manifested. It required all the power of wisdom and patriotism, animated by the affection and engendered by common sufferings and dangers, to keep these rivalries under restraint, and to effect those compromises which it was fondly hoped would insure the harmony and mutual good offices of each for the benefit of all. It was in this spirit of patriotism and confidence in the continuance of such abiding goodwill as would for all time preclude hostile aggression, that Virginia ceded, for the use of the confederated States, all that vast extent of territory lying north of the Ohio River, out of which have since been formed five States and part of a sixth. The addition of these States has accrued entirely to the preponderance of the Northern section over that from which the donation proceeded, and to the disturbance of that equilibrium which existed at the close of the War of the Revolution.

It may not be out of place here to refer to the fact that the grievances which led to that war were directly inflicted upon the Northern colonies. Those of the South had no material cause of complaint; but, actuated by sympathy for their Northern brethren, and a devotion to the principles of civil liberty and community independence, which they had inherited from their Anglo Saxon ancestry, and which were set forth in the Declaration of Independence, they made common cause with their neighbors, and may, at least, claim to have done their full share in the war that ensued.

By the exclusion of the South, in 1820, from all that part of the Louisiana Purchase lying north of the parallel of 36° 30′, and not included in the State of Missouri; by the extension of that line of exclusion to embrace the territory acquired from Texas; and by the appropriation of all the territory obtained from Mexico under the Treaty of Guadalupe — Hidalgo, both north and south of that line, it may be stated with approximate accuracy that the North had monopolized to herself more than three — fourths of all that had been added to the domain of the United States since the Declaration of Independence. This inequality, which began, as has been shown, in the more generous than wise confidence of the South, was employed to obtain for the North the lion’s share of what was afterward added at the cost of the public treasure and the blood of patriots. I do not care to estimate the relative pro portion contributed by each of the two sections.

Nor was this the only cause that operated to disappoint the reasonable hopes and to blight the fair prospects under which the original compact was formed. Discriminating duties upon imports favored the manufacturing region, which was the North; burdening the export region, which was the South, and so imposing upon the latter a double tax: one by the increased price of articles of consumption, which, so far as they were of home production, went into the pockets of the manufacturer; the other by the diminished value of articles of export, which was so much withheld from the pockets of the agriculturist. In like manner the power of the majority section was employed to appropriate to itself an unequal share of the public disbursements. These combined causes—the possession of more territory, more money, and a wider field for the employment of special labor—all served to attract immigration; and, with increasing population, the greed grew by what it fed on.

This became distinctly manifest when the so-called “Republican” Convention assembled in Chicago, on May 16, 1860, to nominate a candidate for the Presidency. It was a purely sectional body. There were a few delegates present representing an insignificant minority in the “Border States,” Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri; but not one from any State south of the celebrated political line of 36° 30’. It had been the invariable usage with nominating conventions of all parties to select candidates for the Presidency and Vice — Presidency, one from the North and the other from the South; but this assemblage nominated Abraham Lincoln, of Illinois, for the first office, and for the second, Hannibal Hamlin, of Maine, both Northerners.

Lincoln, its nominee for the Presidency, had publicly announced that the Union “could not permanently endure, half slave and half free.” The resolutions adopted contained some carefully worded declarations, well adapted to deceive the credulous who were opposed to hostile aggressions upon the rights of the States. In order to accomplish this purpose, they were compelled to create a fictitious issue, in denouncing what they described as “the new dogma that the Constitution, of its own force, carries slavery into any or all of the territories of the United States”—a “dogma” which had never been held or declared by anybody, and which had no existence outside of their own assertion. There was enough in connection with the nomination to assure the most fanatical foes of the Constitution that their ideas would be the rule and guide of the party.

Meantime the Democratic party had held a convention, composed as usual of delegates from all the States. They met in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 23d, but an unfortunate disagreement with regard to the declaration of principles to be set forth rendered a nomination impracticable. Both divisions of the convention adjourned, and met again in Baltimore in June. Then, having finally failed to come to an agreement, they separated and made their respective nominations apart. Stephen A. Douglas, of Illinois, was nominated by the friends of the doc trine of “popular sovereignty,” with Mr. Fitzpatrick, of Alabama, for the Vice-Presidency. Both these gentlemen at that time were Senators from their respective States. Mr. Fitzpatrick declined the nomination, and his place was filled with the name of Herschel V. Johnson, a distinguished citizen of Georgia.

| Master List | Next—> |

Jefferson Davis begins here John Hay and John Nicolay’s begins here. Abraham Lincoln begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.