There seems to have been a surfeit of these internecine brawls for some time to come, and, indeed, stories of dissensions among the servants of the company in the East are plentifully sprinkled throughout its history, both in this century and the next.

Continuing The Beginning of British Power in India,

our selection from Ledger and Sword: Or, The honourable company of merchants of England trading to the East Indies, 1599-1874 by Henry Beckles Willson published in 1903. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Beginning of British Power in India.

Time: 1612

Place: India

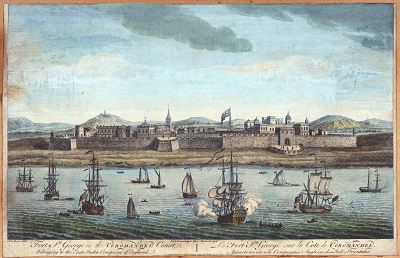

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Powerless to obtain compensation from the Governor of Mocha, Middleton proceeded to make unceremonious levy on all the shipping he could lay his hands upon. On August 16th the Trade’s Increase set sail, in company with the Peppercorn, for Tiku, where two others of the company’s ships were anchored. Middleton very soon discovered that the Trade’s Increase was in a leaky condition; he had hardly got her out of Tiku when she ran aground–for the second time in her brief history. She was floated and brought opposite Pulo Panzang, in Bantam Bay, where the cargo was taken out and stored on shore. The ship, which King James had christened and in which Sir Henry Middleton took such pride, was careened on the beach for repairs. During the process a renegade Spaniard formed a plot to burn her to the water’s edge, and one night carried it successfully into execution–a catastrophe which is said to have so affected the doughty old commander, Sir Henry Middleton, that he sickened and died at Bantam, May 24, 1613.

The many exploits of Middleton, the “doyen” of the company’s servants in the East, well deserve to be read: the hardships he had suffered, the difficulties he had to contend with, the jealous cabals of which he had been the victim. Among the many insubordinates that prevailed, Captain Nicholas Downton, one of the ablest commanders in the service, was not to be persuaded, despite the plots and schemes occasionally undertaken for that purpose, to abandon the respect and loyalty he owed the old sea-dog. Once, when in the Red Sea, Middleton wrote sharply to Downton for an alleged fault; the latter was filled “with admiration and grief.”

“Sir,” he replied, “I can write nothing so plain, nor with that sincerity, but malicious men, when they list, may make injurious construction; but evil come to me if I meant ill to Sir Henry Middleton or any part of the business. God be judge between him and me, if ever I deserved the least evil thought from him. I desire that he were so much himself that he would neither be led nor carried by any injurious person to abuse an inseparable friend.”

Wholly ignorant of the fate reserved for Middleton and the “mightie merchantman,” the Trade’s Increase, Downton resumed command of the Peppercorn and returned direct to England with a full cargo. Many times her timbers sprang aleak on the voyage — for she was but a jerry-built craft at best — but she finally got into the harbor of Waterford, September 13, 1613. Here the rudest of rude welcomes awaited Downton. He was visited by the sheriff and arrested on a warrant from the Earl of Ormond, charged with committing piracy. But, for the present, the plots of his and Middleton’s enemies miscarried; their victim was released, and in a few weeks’ time was back in the Thames. Downton’s proved zeal and endurance won him the applause and favor of the merchant adventurers, and the command of the first voyage under the joint-stock system in the following year.

Meanwhile, each year the company had been sending out a small fleet of ships to the East; it was now beginning also to receive communications from its agents and factors, who, as we have seen, were being slowly distributed at various points east of Aden. Irregular as the receipt of these advices was, and incomplete and belated in themselves, they yet were a useful guide to the company in equipping its new ventures.

“We are in great hope to get good and peaceful trade at Cambay and Surat,” writes Anthony Marlowe to the company from Socotra, “where our ship, by God’s grace, is to ride. Our cloth and lead, we hear, will sell well there; our iron not so well as at Aden; that indigo we shall have good store at reasonable rates; and also calicoes and musk, and at Dabul good pepper; so as I hope in God the Hector shall make her voyage at those places and establish a trade there, to the benefit of your worships and the good of our country.”

For Captain Keeling, Marlowe has many words of praise. “His wisdom, language, and carriage are such as I fear we shall have great want of at Surat in the first settling of our trade.” Of some of the other servants of the company Marlowe is not so enthusiastic, and he does not spare his opinion of their characters. In a subsequent letter we are brought right face to face with a very pretty quarrel between Hippon, the master of the Dragon, and his mate, William Tavernour, in which Hawkins tries to act as peacemaker, but is foiled by the bloodthirsty Matthew Mullinux, master of the Hector, who had himself a private grudge against the said Tavernour, or, as is written here, “a poniard in pickle for the space of six months.”

“And not contented with this (he) afterward came up upon the deck and there before the boatswain and certain of us did most unchristianlike speak these words: that if he might but live to have the opportunity to kill the said Tavernour he would think it to be the happiest day that ever he saw in his life, an it were but with a knife.”

There seems to have been a surfeit of these internecine brawls for some time to come, and, indeed, stories of dissensions among the servants of the company in the East are plentifully sprinkled throughout its history, both in this century and the next. Of hints for trade the company’s agents are profuse in this growing correspondence.

“There is an excellent linen,” writes one of them, “made at Cape Comorin, and may be brought hither from Cochin in great abundance if the Portugals would be quiet men. It is about two yards broad or better and very strong cloth, and is called _cachade Comoree_. It would certainly sell well in England for sheeting.” Here we see the genesis of the calico trade.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.