All this, it must be admitted, was quite consistent with the oft repeated declaration that the Constitution was a “covenant with hell,” which stood as the caption of a leading abolitionist paper of Boston.

Continuing South Secedes from the United States,

with a selection from Davis’s Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government by Jefferson Davis published in 1881. This selection is presented in 4.5 installments for 5 minute reading.

Previously in South Secedes from the United States.

Time: 1860

Place: Southern United States

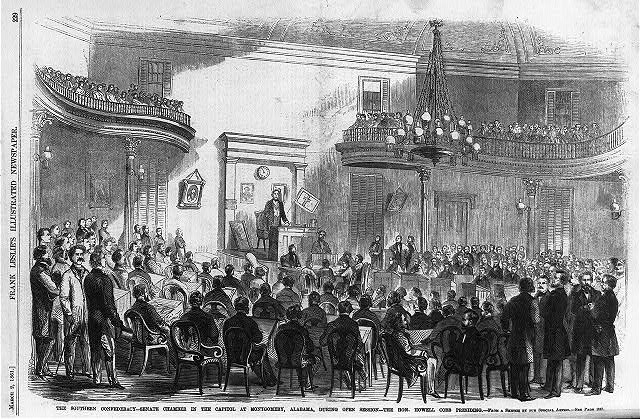

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Ten years before, John C. Calhoun, addressing the Senate with all the earnestness of his nature, and with that sincere desire to avert the danger of disunion which those who knew him best never doubted, had asked the emphatic question, “How can the Union be saved?” He answered his question thus: “There is but one way by which it can be [saved] with any certainty; and that is by a full and final settlement, on the principles of justice, of all the questions at issue between the sections. The South asks for justice, simple justice, and less she ought not to take. She has no compromise to offer but the Constitution, and no con cession or surrender to make. Can this be done? Yes, easily! Not by the weaker party; for it can of itself do nothing—not even protect itself—but by the stronger. But will the North agree to do this? It is for her to answer this question. But, I will say, she cannot refuse if she has half the love of the Union which she professes to have, nor without exposing herself to the charge that her love of power and aggrandizement is far greater than her love of the Union.”

During the ten years that intervened between the date of this speech and the message of Buchanan cited above, the progress of sectional discord and the tendency of the stronger section to un constitutional aggression had been fearfully rapid. With very rare exceptions, there were none in 1850 who claimed the right of the Federal Government to apply coercion to a State. In 1860 men had grown to be familiar with threats of driving the South into submission to any act that the Government, in the hands of a Northern majority, might see fit to perform. During the canvass of that year, demonstrations had been made by quasi — military organizations in various parts of the North, which looked unmistakably to purposes widely different from those enunciated in the preamble of the Constitution, and to the employment of means not authorized by the powers which the States had dele gated to the Federal Government.

Well-informed men still remembered that, in the convention which framed the Constitution, a proposition was made to authorize the employment of force against a delinquent State, on which Madison said: “The use of force against a State would look more like a declaration of war than an infliction of punishment, and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might have been bound.” The convention expressly refused to confer the power proposed, and the clause was lost. While therefore in 1860 many violent men, appealing to passion and the lust of power, were inciting the multitude, and preparing Northern opinion to support a war waged against the Southern States in the event of their secession, there were others who took a different view of the case. Notable among such was the New York Tribune, which had been the organ of the abolitionists, and which now declared that, “If the cotton States wished to withdraw from the Union, they should be allowed to do so”; that “any attempt to compel them to remain, by force, would be contrary to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and to the fundamental ideas upon which human liberty is based”; and that “if the Declaration of Independence justified the secession from the British Empire of three millions of subjects in 1776, it was not seen why it would not justify the secession of five millions of Southerners from the Union in 1861.” Again, it was said by the same journal that, “Sooner than compromise with the South and abandon the Chicago platform,” they would “let the Union slide.” Taunting expressions were freely used, as, for example: “If the Southern people wish to leave the Union, we will do our best to forward their views.”

All this, it must be admitted, was quite consistent with the oft repeated declaration that the Constitution was a “covenant with hell,” which stood as the caption of a leading abolitionist paper of Boston. That signs of coming danger so visible, evidences of hostility so unmistakable, disregard of constitutional obligations so wanton, taunts and jeers so bitter and insulting, should serve to increase excitement in the South, were consequences flowing as much from reason and patriotism as from sentiment. He must have been ignorant of human nature who did not expect such a tree to bear fruits of discord and division.

In November, 1860, after the result of the Presidential election was known, the Governor of Mississippi, having issued his proclamation convoking a special session of the Legislature to consider the propriety of calling a convention, invited the Senators and Representatives of the State in Congress to meet him for consultation as to the character of the message he should send to the Legislature when assembled.

While holding, in common with my political associates, that the right of a State to secede was unquestionable, I differed from most of them as to the probability of our being permitted peace ably to exercise the right. The knowledge acquired by the administration of the War Department for four years, and by the chairmanship of the Military Committee of the Senate at two different periods, still longer in combined duration, had shown me the entire lack of preparation for war in the South. The foundries and armories were in the Northern States, and there were stored all the new and improved weapons of war. In the arsenals of the Southern States were to be found only arms of the old and rejected models. The South had no manufactories of powder, and no navy to protect our harbors, no merchant — ships for foreign commerce. It was evident to me, therefore, that, if we should be involved in war, the odds against us would be far greater than what was due merely to our inferiority in population. Believing that secession would be the precursor of war between the States, I was consequently slower and more reluctant than others, who entertained a different opinion, to resort to that remedy.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Jefferson Davis begins here John Hay and John Nicolay’s begins here. Abraham Lincoln begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.