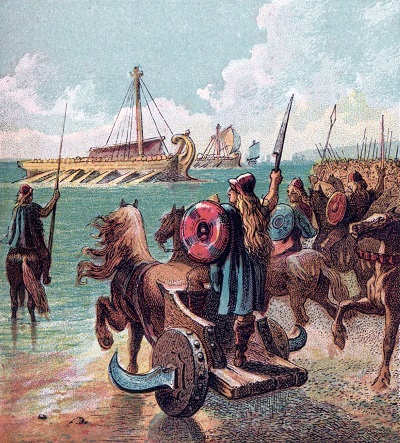

This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Julius Caesar Lands on Britain.

Introduction

Britain beckoned to the Romans in a way that Germany did not. The story of the Roman conquest of Britain is here told from the first reconnaissance by Julius Caesar to the conquest of Agricola a century later is told by Goldsmith, the great poet and novelist who also wrote a multi-volume history.

This selection is from The History of England: from Earliest Times to the Death George II by Oliver Goldsmith published in 1814. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Oliver Goldsmith was an Irish writer of the eighteenth century who wrote such classic novels as The Vicar of Wakefield and poems such as The Deserted Village.

Time: 55 – 54 BC

Place: Britainnia

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The Britons in their rude and barbarous state seemed to stand in need of more polished instructors; and indeed whatever evils may attend the conquest of heroes, their success has generally produced one good effect in disseminating the arts of refinement and humanity. It ever happens when a barbarous nation is conquered by another more advanced in the arts of peace, that it gains in elegance a recompense for what it loses in liberty.

The Britons had long remained in this rude but independent state, when Caesar, having overrun Gaul with his victories, and willing still further to extend his fame, determined upon the conquest of a country that seemed to promise an easy triumph. He was allured neither by the riches nor by the renown of the inhabitants; but being ambitious rather of splendid than of useful conquests, he was willing to carry the Roman arms into a country the remote situation of which would add seeming difficulty to the enterprise and consequently produce an increase of reputation. His pretence was to punish these islanders for having sent succors to the Gauls while he waged war against that nation, as well as for granting an asylum to such of the enemy as had sought protection from his resentment.

The natives, informed of his intention, were sensible of the unequal contest and endeavored to appease him by submission. He received their ambassadors with great complacency, and having exhorted them to continue steadfast in the same sentiments, in the meantime made preparations for the execution of his design. When the troops designed for the expedition were embarked he set sail for Britain about midnight, and the next morning arrived on the coast near Dover, where he saw the rocks and cliffs covered with armed men to oppose his landing.

Finding it impracticable to gain the shore where he first intended, from the agitation of the sea and the impending mountains, he resolved to choose a landing — place of greater security. The place he chose was about eight miles farther on (some suppose at Deal), where an inclining shore and a level country invited his attempts. The poor, naked, ill-armed Britons we may well suppose were but an unequal match for the disciplined Romans who had before conquered Gaul and afterward became the conquerors of the world. However, they made a brave opposition against the veteran army; the conflicts between them were fierce, the losses mutual, and the success various.

The Britons had chosen Cassibelaunus for their commander-in-chief; but the petty princes under his command, either desiring his station or suspecting his fidelity, threw off their allegiance. Some of them fled with their forces into the internal parts of the kingdom, others submitted to Caesar; till at length Cassibelaunus himself, weakened by so many desertions, resolved upon making what terms he was able while yet he had power to keep the field. The conditions offered by Caesar and accepted by him were that he should send to the Continent double the number of hostages at first demanded and that he should acknowledge subjection to the Romans.

The Romans were pleased with the name of this new and remote conquest, and the senate decreed a supplication of twenty days in consequence of their general’s success. Having therefore in this manner rather discovered than subdued the southern parts of the island, Caesar returned into Gaul with his forces and left the Britons to enjoy their customs, religion, and laws. But the inhabitants, thus relieved from the terror of his arms, neglected the performance of their stipulations, and only two of their states sent over hostages according to the treaty. Caesar, it is likely, was not much displeased at the omission, as it furnished him with a pretext for visiting the island once more and completing a conquest which he had only begun.

Accordingly the ensuing spring he set sail for Britain with eight hundred ships,[*] and arriving at the place of his descent he landed without opposition. The islanders being apprised of his invasion had assembled an army and marched down to the sea-side to oppose him, but seeing the number of his forces, and the whole sea, as it were, covered with his shipping, they were struck with consternation and retired to their places of security. The Romans, however, pursued them to their retreats until at last common danger induced these poor barbarians to forget their former dissensions and to unite their whole strength for the mutual defense of their liberty and possessions.

[* With regard to these Roman ships, let not our readers be misled by a familiar notion or a pompous name. They were but little more than rowboats, as may be easily imagined from the fact that Cicero instances for its uncommon magnitude a ship of only fifty-six tons! These ancient vessels were occasionally sheathed with leather or lead, and had the prow decorated with paint and gilding, while the stern was sometimes carved in the figure of a shield, elaborately adorned. Upon a staff there erected hung ribbons distinctive of the ship and serving at the same time to show the direction of the wind. There, too, stood the tutela, or chosen patron of the ship, to whom prayers and sacrifices were daily offered. The selection of this deity was guided by either private or professional reasons, and as merchants committed themselves to the protection of Mercury, or lovers to the care of Cupid, warriors, it will at once be surmised, made Mars the object of their pious supplication.

At a later period than the epoch to which our present note attaches, when Constantius removed from Heliopolis to Rome an enormous obelisk, weighing fifteen hundred tons, the vessel on board of which it was shipped also carried eleven hundred and thirty-eight tons of pulse; but such vast and unmanageable masses were regarded as monsters, and owed their existence to the absolute urgency of a remarkable purpose, backed by the despotic institutions of the times.]

Cassibelaunus was chosen to conduct the common cause, and for some time he harassed the Romans in their march and revived the desponding hopes of his countrymen. But no opposition that undisciplined strength could make was able to repress the vigor and intrepidity of Caesar. He discomfited the Britons in every action; he advanced into the country, passed the Thames in the face of the enemy, took and burned the capital city of Cassibelaunus, established his ally Mandubratius as sovereign of the Trinobantes; and having obliged the inhabitants to make new submissions, he again returned with his army into Gaul, having made himself rather the nominal than the real possessor of the island.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.