But what could undisciplined bravery avail against the attack of an army skilled in all the arts of war and inspired by a long train of conquests?

Continuing Romans Conquer Britain,

our selection from The History of England: from Earliest Times to the Death George II by Oliver Goldsmith published in 1814. The selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Romans Conquer Britain.

Time: 44 – 60 AD

Place: Britainnia

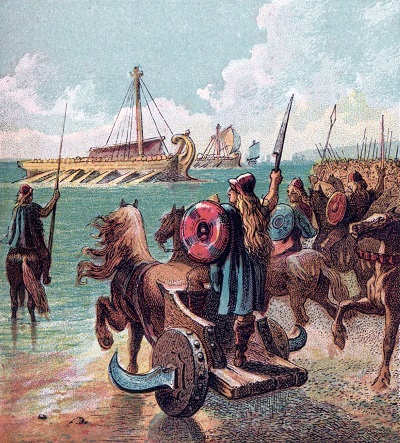

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Whatever the stipulated tribute might have been, it is more than probable, as there was no authority left to exact it, that it was but indifferently paid. Upon the accession of Augustus, that Emperor had formed a design of visiting Britain, but was diverted from it by an unexpected revolt of the Pannonians. Some years after he resumed his design; but being met in his way by the British ambassadors, who promised the accustomed tribute and made the usual submissions, he desisted from his intention. The year following, finding them remiss in their supplies and untrue to their former professions, he once more prepared for the invasion of the country; but a well-timed embassy again averted his indignation, and the submissions he received seemed to satisfy his resentment; upon his death-bed he appeared sensible of the overgrown extent of the Roman Empire and recommended it to his successors never to enlarge their territories.

Tiberius followed the maxims of Augustus and, wisely judging the empire already too extensive, made no attempt upon Britain. Some Roman soldiers having been wrecked on the British coast the inhabitants not only assisted them with the greatest humanity, but sent them in safety back to their general. In consequence of these friendly dispositions, a constant intercourse of good offices subsisted between the two nations; the principal British nobility resorted to Rome, and many received their education there.

From that time the Britons began to improve in all the arts which contribute to the advancement of human nature. The first art which a savage people is generally taught by politer neighbors is that of war. The Britons thenceforward, though not wholly addicted to the Roman method of fighting, nevertheless adopted several of their improvements, as well in their arms as in their arrangement in the field. Their ferocity to strangers, for which they had been always remarkable, was mitigated and they began to permit an intercourse of commerce even in the internal parts of the country. They still, however, continued to live as herdsmen and hunters; a manifest proof that the country was yet but thinly inhabited. A nation of hunters can never be populous, as their subsistence is necessarily diffused over a large tract of country, while the husbandman converts every part of nature to human use, and flourishes most by the vicinity of those whom he is to support.

The wild extravagances of Caligula by which he threatened Britain with an invasion served rather to expose him to ridicule than the island to danger. The Britons therefore for almost a century enjoyed their liberty unmolested, till at length the Romans in the reign of Claudius began to think seriously of reducing them under their dominion. The expedition for this purpose was conducted in the beginning by Plautius and other commanders, with that success which usually attended the Roman arms.

Claudius himself, finding affairs sufficiently prepared for his reception, made a journey thither and received the submission of such states as living by commerce were willing to purchase tranquility at the expense of freedom. It is true that many of the inland provinces preferred their native simplicity to imported elegance and, rather than bow their necks to the Roman yoke, offered their bosoms to the sword. But the southern coast with all the adjacent inland country was seized by the conquerors, who secured the possession by fortifying camps, building fortresses, and planting colonies. The other parts of the country, either thought themselves in no danger or continued patient spectators of the approaching devastation.

Caractacus was the first who seemed willing, by a vigorous effort, to rescue his country and repel its insulting and rapacious conquerors.[*] The venality and corruption of the Roman praetors and officers, who were appointed to levy the contributions in Britain, served to excite the indignation of the natives and give spirit to his attempts. This rude soldier, though with inferior forces, continued for about the space of nine years to oppose and harass the Romans; so that at length Ostorius Scapula was sent over to command their armies. He was more successful than his predecessors. He advanced the Roman conquest over Britain, pierced the country of the Silures, a warlike nation along the banks of the Severn, and at length came up with Caractacus, who had taken possession of a very advantageous post upon an almost inaccessible mountain, washed by a deep and rapid stream.

[*: The character of this hero has been powerfully depicted by Beaumont and Fletcher, in one of their noblest dramas.]

The unfortunate British general, when he saw the enemy approaching, drew up his army, composed of different tribes, and going from rank to rank exhorted them to strike the last blow for liberty, safety, and life. To these exhortations his soldiers replied with shouts of determined valor. But what could undisciplined bravery avail against the attack of an army skilled in all the arts of war and inspired by a long train of conquests? The Britons were, after an obstinate resistance, totally routed, and a few days after Caractacus himself was delivered up to the conquerors by Cartismandua, queen of the Brigantes, with whom he had taken refuge. The capture of this general was received with such joy at Rome that Claudius commanded that he should be brought from Britain in order to be exhibited as a spectacle to the Roman people. Accordingly, on the day appointed for that purpose, the Emperor, ascending his throne, ordered the captives and Caractacus among the number to be brought into his presence. The vassals of the British King, with the spoils taken in war, were first brought forward; these were followed by his family, who, with abject lamentations, were seen to implore for mercy.

Last of all came Caractacus with an undaunted air and a dignified aspect. He appeared no way dejected at the amazing concourse of spectators that were gathered upon this occasion, but, casting his eyes on the splendors that surrounded him, “Alas!” cried he, “how is it possible that a people possessed of such magnificence at home could envy me an humble cottage in Britain?” When brought into the Emperor’s presence he is said to have addressed him in the following manner: “Had my moderation been equal to my birth and fortune, I had arrived in this city not as a captive, but as a friend. But my present misfortunes redound as much to your honor as to my disgrace; and the obstinacy of my opposition serves to increase the splendor of your victory. Had I surrendered myself in the beginning of the contest, neither my disgrace nor your glory would have attracted the attention of the world, and my fate would have been buried in general oblivion. I am now at your mercy; but if my life be spared, I shall remain an eternal monument of your clemency and moderation.” The Emperor was affected with the British hero’s misfortunes and won by his address. He ordered him to be unchained upon the spot, with the rest of the captives, and the first use they made of their liberty was to go and prostrate themselves before the empress Agrippina, who as some suppose had been an intercessor for their freedom.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.