Proud as it is, its very splendor shows the marks of a barbarous age.

Continuing The First Written Free Constitution In The World,

with a selection from The History of Connecticut, From the First Settlement of the Colony by Gideon H. Hollister published in 1858. This selection is presented in 2.5 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The First Written Free Constitution In The World.

Time: 1639 – 1643

Place: Connecticut

CC BY-SA 3.0Wikipedia.

6. These two regular courts were to be convened by the governor himself, or by his secretary, by sending out a warrant to the constables of every town, a month at least before the day of session. In times of danger or public exigency the governor and a majority of the magistrates might order the secretary to summon a court, with fourteen days’ notice, or even less, if the case required it, taking care to state their reasons for so doing to the deputies when they met. If, on the other hand, the governor should neglect to call the regular courts, or, with the major part of the magistrates, should fail to convene such special ones as were needed, then the freemen, or a major part of them, were required to petition them to do it. If this did not serve, then the freemen, or a majority of them, were clothed with the power to order the constables to summon the court, after which they might meet, choose a moderator, and do any act that it was lawful for the regular courts to do.

7. On receiving the warrants for these general courts the constables of each town were to give immediate notice to the freemen, either at a public gathering or by going from house to house, that at a given place and time they should meet to elect deputies to the general court, about to convene, and “to agitate the affairs of the commonwealth.” These deputies were to be chosen by vote of the electors of the town who had taken the oath of fidelity; and no man not a freeman was eligible to the office of deputy. The deputies were to be chosen by a major vote of all the freemen present, who were to make their choice by written paper ballots–each voter giving in as many papers as there were deputies to be chosen, with a single name written on each paper. The names of the deputies when chosen were indorsed by the constables, on the back of their respective warrants, and returned into court.

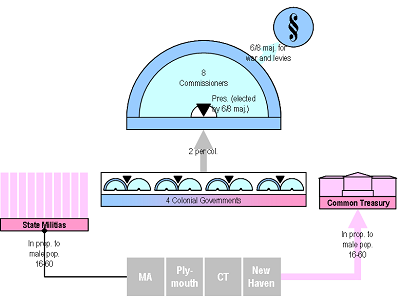

8. The three towns of the commonwealth were each to have the privilege of sending four deputies to the general court. If other towns were afterward added to the jurisdiction, the number of their deputies was to be fixed by the court. The deputies represented the towns, and could bind them by their votes in all legislative matters.

9. The deputies had power to meet after they were chosen and before the session of the general court, to consult for the public good, and to examine whether those who had been returned as members of their own body were legally elected. If they found any who were not so elected, they might seclude them from their assembly, and return their names to the court, with their reasons for so doing. The court, on finding these reasons valid, could issue orders for a new election, and impose a fine upon such men as had falsely thrust themselves upon the towns as candidates.

10. Every regular general court was to consist of the governor and at least four other magistrates, with the major part of the deputies chosen from the several towns. But if any court happened to be called by the freemen, through the default of the governor and magistrates, that court was to consist of a majority of the freemen present, or their deputies, and a moderator, chosen by them. In the general court was lodged the “supreme power of the commonwealth.” In this court the governor or moderator had power to command liberty of speech, to silence all disorders, and to put all questions that were to be made the subject of legislative action, but not to vote himself unless the court was equally divided, when he was to give the casting vote. But he could not adjourn or dissolve the court without the major vote of the members. Taxes also were to be ordered by the court; and when they had agreed upon the sum to be raised, a committee was to be appointed of an equal number of men from each town to decide what part of that sum each town should pay.

This first constitution of the New World was simple in its terms, comprehensive in its policy, methodical in its arrangement, beautiful in its adaptation of parts to a whole, of means to an end. Compare it with any of the constitutions of the Old World then existing. I say nothing of those libels upon human nature, the so-called constitutions of the Continent of Europe — compare it reverently, as children speak of a father’s roof, with that venerated structure, the British Constitution. How complex is the architecture of the latter! here exhibiting the clumsy work of the Saxon, there the more graceful touch of later conquerors; the whole colossal pile, magnificent with turrets and towers, and decorated with armorial devices and inscriptions, written in a language not only dead, but never native to the island; all eloquent, indeed, with the spirit of ages past, yet haunted with the cry of suffering humanity and the clanking of chains that come up from its subterranean dungeons.

Mark, too, the rifts and seams in its gray walls — traces of convulsion and revolution. Proud as it is, its very splendor shows the marks of a barbarous age. Its tapestry speaks a language dissonant to the ears of freemen. It tells of exclusive privileges, of divine rights, not in the people, but in the king, of primogeniture, of conformities, of prescriptions, of serfs and lords, of attainder that dries up like a leprosy the fountains of inheritable blood; and, lastly, it discourses of the rights of British subjects, in eloquent language, but sometimes with qualifications that startle the ears of men who have tasted the sweets of a more enlarged liberty. Such was the spirit of the British Constitution, and code of the seventeenth century. I do not blame it that it was not better; perhaps it could not then have been improved without risk. Improvement in an old state is the work of time. But I have a right to speak with pride of the more advanced freedom of our own.

The Constitution of Connecticut sets out with the practical recognition of the doctrine that all ultimate power is lodged with the people. The body of the people is the body politic. From the people flow the fountains of law and justice. The governor and the other magistrates, the deputies themselves, are but a kind of committee, with delegated powers to act for the free planters. Elected from their number, they must spend their short official term in the discharge of the trust, and then descend to their old level of citizen voters. Here are to be no interminable parliaments. The majority of the general court can adjourn it at will. Nor is there to be an indefinite prorogation of the Legislature at the will of a single man. Let the governor and the magistrates look to it. If they do not call a general court, the planters will take the matter into their own hands and meet in a body to take care of their neglected interests.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Gideon H. Hollister begins here. John Marshall begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.