In his voyage Bering was struck by the absence of such great and high waves as in other places are common to the open sea, and he observed fir-trees floating in the water, although they were unknown on the Asiatic coast.

Continuing The Alaska Purchase,

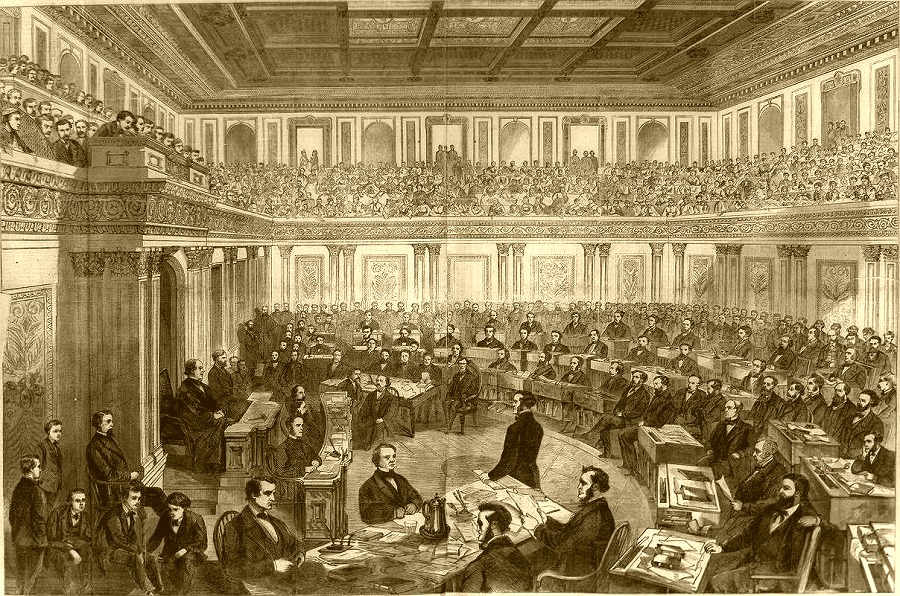

our selection from Charles Sumner’s Speech to the Senate During the Alaskan Treaty Ratification Debate in 1867. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Alaska Purchase.

Time: 1867

Place: Washington, D.C.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The Czar died in the winter of 1725; but the Empress Catharine, faithful to the desires of her husband, did not allow this work to be neglected. Vitus Bering, a Dane by birth and a navigator of some experience, was made commander. The place of embarkation was on the other side of the Asiatic continent. Taking with him officers and shipbuilders, the navigator left St. Petersburg by land on February 5, 1725, and began the preliminary journey across Siberia, and the Sea of Okhotsk to the coast of Kamchatka, which they reached after infinite hard ships and delays, sometimes with dogs for draft, and sometimes supporting life by eating leather bags, straps, and shoes. More than three years were passed in this toilsome and perilous journey to the place of embarkation. At last, on July 20, 1728, the party was able to set sail in a small vessel, called the Gabriel, described as “like the packet-boats used in the Baltick.” Steering in a northeasterly direction, Bering passed a large island, which he called St. Lawrence, for the saint on whose day it was seen. This island, which is included in the present cession, may be considered the first point in Russian discovery, as it is also the first outpost of the North American continent. Continuing northward, and hugging the Asiatic coast, Bering turned back only when he thought he had reached the northeastern extremity of Asia, and was satisfied that the two continents were separated from each other. He did not go farther north than 67° 30’.

In his voyage Bering was struck by the absence of such great and high waves as in other places are common to the open sea, and he observed fir-trees floating in the water, although they were unknown on the Asiatic coast. Relations of inhabitants, in harmony with these indications, pointed to a “country at no great distance toward the east.” His work was still incomplete, and the navigator, before returning home, put forth again for this discovery, but without success. By another dreary land journey he made his way back to St. Petersburg in March, 1730, after an absence of five years.

The spirit of discovery continued at St. Petersburg. A Cossack chief, undertaking to conquer the obstinate natives on the northeastern coast, proposed also “to discover the pretended country on the frozen sea.” But he was killed by an arrow before his enterprise was completed. Little is known of the result; but it is said that the navigator whom he had selected, by name Gwosdew, in 1730 succeeded in reaching a “strange coast” between 65° and 66° of north latitude, where he saw persons, but could not speak with them for want of an interpreter. This must have been the coast of North America, not far from the group of islands in Bering Strait through which the present boundary passes.

The desire of the Russian Government to get behind the curtain increased. Bering volunteered to undertake the discoveries that remained to be made. He was created a commodore, and his old lieutenants were made captains. Several academicians were appointed to report on the natural history of the coasts visited, among whom was Steller, the naturalist. All these, with a numerous body of officers, journeyed across Siberia (northern Asia) and the Sea of Okhotsk, to Kamchatka, as Bering had journeyed before. Though ordered in 1738, the expedition was not able to leave the western coast until June 4, 1741, when two well-appointed ships set sail in company “to discover the continent of America.” One of these, called the St. Paul, was under Commodore Bering; the other, called the St. Peter, was under Captain Tschirikoff. For some time the two kept together; but in a violent storm and fog they were separated, when each continued the expedition alone. .

Bering first saw the continent of North America on July 18, 1741, in latitude 58° 28′. Looking at it from a distance “the country had terrible high mountains that were covered with snow.” Two days later he anchored in a sheltered bay near a point which he called, for the saint day on which he saw it, Cape St. Elias. He was in the shadow of Mount St. Elias. On landing he found deserted huts, fireplaces, hewn wood, house hold furniture, an arrow, edge-tools of copper, with “store of red salmon.” Here also several birds unknown in Siberia were noticed by the faithful Steller. Steering northward, Bering found himself constrained by the elbow in the coast to turn west ward, and then in a southerly direction. Hugging the shore, his voyage was arrested by islands without number, among which he zigzagged to find his way. Several times he landed, and on one of these occasions he saw natives, who wore upper garments of whales’ guts, breeches of sealskins, caps of the skins of sea-lions, adorned with various feathers, especially those of hawks.” These “Americans,” as they are called, were fishermen, without bows and arrows. This was on one of the Shumagin Islands, near the southern coast of the Peninsula of Alaska.

Meanwhile, the other solitary ship, proceeding on its way, had sighted the same coast, July I 5, 1741, in latitude 56°. Anchoring at some distance from the steep and rocky cliffs before him, Tschirikoff sent his mate with the long-boat and ten of his best men, provided with small arms and a brass cannon, to inquire into the nature of the country and to obtain fresh water. The long-boat disappeared in a small wooded bay, and was never seen again. The captain sent his boatswain, with the small boat and carpenters, well armed, to furnish assistance. But the small boat disappeared also, and was never seen again. At the same time a great smoke was observed continually ascending from the shore. Shortly afterward two boats filled with natives sallied forth and lay at some distance from the vessel, when, crying “A gai! A gail” they put back to the shore. Sorrowfully the Russian navigator turned away, not knowing the fate of his comrades and unable to help them. This was not far from Sitka.

Such was the first discovery of these northwestern coasts, and such are the first recorded glimpses of the aboriginal inhabitants. Tschirikoff, deprived of his boats, and therefore unable to land, hurried home.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.