Today’s installment concludes The First Written Free Constitution In The World,

the name of our combined selection from Gideon H. Hollister and John Marshall. First we finish up Holister. Then the concluding installment, by John Marshall from History of the Colonies Planted by the English, was published in 1824. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed three thousand words from great works of history. Congratulations!

John Marshall was the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. First we conclude Hollister.

Previously in The First Written Free Constitution In The World.

Time: 1639 – 1643

Place: Connecticut

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

One of the most striking features in this new and at the same time strange document is that it will tolerate no rotten-borough system. Every deputy who goes to the Legislature is to go from his own town, and is to be a free planter of that town. In this way he will know what is the will of his constituents and what their wants are.

This paper has another remarkable trait. There is to be no taxation without representation in Connecticut. The towns, too, are recognized as independent municipalities. They are the primary centres of power older than the constitution–the makers and builders of the State. They have given up to the State a part of their corporate powers, as they received them from the free planters, that they may have a safer guarantee for the keeping of the rest. Whatever they have not given up they hold in absolute right.

How strange, too, that in defining so carefully and astutely the limits of the government, these constitution-makers should have forgotten the King. One would but suppose that those who indited this paper were even aware of the existence of titled majesty beyond what belonged to the King of kings. They mention no supreme power save that of the commonwealth, which speaks and acts through the general court.

Such was the Constitution of Connecticut. I have said it was the oldest of the American constitutions. More than this, I might say, it is the mother of them all. It has been modified in different States to suit the circumstances of the people and the size of their respective territories; but the representative system peculiar to the American republics was first unfolded by Ludlow–who probably drafted the Constitution of Connecticut–and by Hooker, Haynes, Wolcott, Steele, Sherman, Stone, and the other far-sighted men of the colony, who must have advised and counselled to do what they and all the people in the three towns met together in a mass to sanction and adopt as their own. Let me not be understood to say that I consider the framers of this paper perfect legislators or in all respects free from bigotry and intolerance. How could they throw off in a moment the shackles of custom and old opinion? They saw more than two centuries beyond their own era. England herself at this day has only approximated, without reaching, the elevated table-land of constitutional freedom, whose pure air was breathed by the earliest planters of Connecticut. Under this constitution they passed, it is true, some quaint laws, that sometimes provoke a smile, and, in those who are unmindful of the age in which they lived, sometimes a sneer.

I shall speak of these laws in order, I hope with honesty and not too much partiality. It may be proper to say here, however, that for one law that has been passed in Connecticut of a bigoted or intolerant character, a diligent explorer into the English court records or statute-books for evidences of bigotry and revolting cruelty could find twenty in England. “Kings have been dethroned,” says Bancroft, the eloquent American historian, “recalled, dethroned again, and so many constitutions framed or formed, stifled or subverted, that memory may despair of a complete catalogue; but the people of Connecticut have found no reason to deviate essentially from the government as established by their fathers. History has ever celebrated the commanders of armies on which victory has been entailed, the heroes who have won laurels in scenes of carnage and rapine. Has it no place for the founders of states, the wise legislators who struck the rock in the wilderness, and the waters of liberty gushed forth in copious and perennial fountains?”

by John Marshall

About this period many evidences were given of a general combination of the neighboring Indians against the settlements of New England; and apprehensions were also entertained of hostility from the Dutch of Manhadoes. A sense of impending danger suggested the policy of forming a confederacy of the sister-colonies for their mutual defense. And so confirmed had the habit of self-government become since the attention of England was absorbed in her domestic dissensions that it was not thought necessary to consult the parent state on this important measure. After mature deliberation articles of confederation were digested; and in May, 1643, they were conclusively adopted.

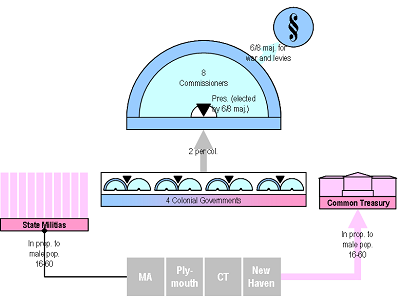

By them “The United Colonies of New England” — Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven — entered into a firm and perpetual league, offensive and defensive.

Each colony retained a distinct and separate jurisdiction; no two colonies could join in one jurisdiction without the consent of the whole; and no other colony could be received into the confederacy without the like consent.

The charge of all wars was to be borne by the colonies respectively, in proportion to the male inhabitants of each between sixteen and sixty years of age.

On notice of an invasion given by three magistrates of any colony, the confederates were immediately to furnish their respective quotas. These were fixed at one hundred from Massachusetts, and forty-five from each of the other parties to the agreement. If a larger armament should be found necessary, commissioners were to meet and ascertain the number of men to be required.

Two commissioners from each government, being church members, were to meet annually on the first Monday in September. Six possessed the power of binding the whole. Any measure approved by a majority of less than six was to be referred to the general court of each colony, and the consent of all was necessary to its adoption.

They were to choose annually a president from their own body, and had power to frame laws or rules of a civil nature and of general concern. Of this description were rules which respected their conduct toward the Indians, and measures to be taken with fugitives from one colony to another.

No colony was permitted, without the general consent, to engage in war, but in sudden and inevitable cases.

If, on any extraordinary meeting of the commissioners, their whole number should not assemble, any four who should meet were empowered to determine on a war, and to call for the respective quotas of the several colonies, but not less than six could determine on the justice of the war or settle the expenses or levy the money for its support.

If any colony should be charged with breaking an article of the agreement, or with doing an injury to another colony, the complaint was to be submitted to the consideration and determination of the commissioners of such colonies as should be disinterested.

This union, the result of good-sense and of a judicious consideration of the real interests of the colonies, remained in force until their charters were dissolved. Rhode Island, at the instance of Massachusetts, was excluded; and her commissioners were not admitted into the congress of deputies, which formed the confederation.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our selections on The First Written Free Constitution In The World (1639) – Earliest Union Among American Colonies (1643) by two of the most important authorities of this topic:

- The History of Connecticut, From the First Settlement of the Colony by Gideon H. Hollister published in 1858.

- History of the Colonies Planted by the English by John Marshall published in 1824.

Gideon H. Hollister begins here.

This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The First Written Free Constitution In The World (A.D. 1639) – Earliest Union Among American Colonies (A.D. 1643) here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.