This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Historians Can Directly See Foundation of a Government for First Time.

Introduction

That a colonizing people should, almost at the moment of their arrival in a new home, proceed to enact the fundamental law of a civil state is a remarkable fact in history. The manner in which this was done in Connecticut, and the character of the constitution there made in 1639, six years after the first English settlement, render it a memorable event in the development of American government.

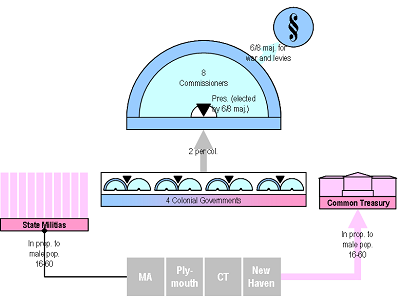

As the Connecticut Constitution was not only the first instrument of its kind, but also formed, in many respects, a pattern for others which became the organic laws of American States, so the first union of colonies, in 1643, is important not alone as being the first, but also as foreshadowing the later confederation and the final union of the States themselves.

This model of an American union, following so closely upon the earliest creation of an American civil constitution, is concisely described by the great Chief Justice Marshall.

The selections are from:

- The History of Connecticut, From the First Settlement of the Colony by Gideon H. Hollister published in 1858.

- History of the Colonies Planted by the English by John Marshall published in 1824.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. There’s 2.5 installments by Gideon H. Hollister and 0.5 installments by John Marshall. We begin with Gideon H. Hollister.

Gideon H. Hollister was an American state legislator, diplomat, and historian, especially noted for his two volume History of Connecticut. John Marshall was the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Time: 1639 – 1643

Place: Connecticut

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

We read, in treatises upon elementary law, of a time antecedent to all law, when men theoretically are said to have met together and surrendered a part of their rights for a more secure enjoyment of the remainder. Hence, we are told, human governments date their origin. This dream of the enthusiast as applied to ages past, in Connecticut for the first time and upon the American soil became a recorded verity.

Here at last we are permitted to look on and see the foundations of a political structure laid. We can count the workmen, and we have become familiar with the features of the master-builders. We see that they are most of them men of a new type. Bold men they are, who have cut loose from old associations, old prejudices, old forms; men who will take the opinions of no man unless he can back them up with strong reasons; clear-sighted, sinewy men, in whom the intellect and the moral nature predominate over the more delicate traits that mark an advanced stage of social life. Such men as these will not, however, in their zeal to cast off old dominions, be solicitous to free themselves and their posterity from all restraint; for no people are less given up to the sway of unbridled passions. Indeed, they have made it a main part of their business in life to subdue their passions. Laws, therefore, they must and will have, and laws that, whatever else they lack, will not want the merit of being fresh and original.

As it has been, and still is, a much debated question, what kind of men they were — some having overpraised and others rashly blamed them–let us, without bigotry, try if we cannot look at them through a medium that shall render them to us in all their essential characteristics as they were. That medium is afforded us by the written constitution that they made of their own free will for their own government. This is said to give the best portrait of any people; though in a nation that has been long maturing, the compromise between the past and present, written upon almost every page of its history, cannot have failed in some degree to make the likeness dim. Yet, of such a people as we are describing, who may be said to have no past, who live not so much in the present as in the future, and who forge as with one stroke the constitution that is to be a basis of their laws–are we not provided with a mirror that reflects every lineament with the true disposition of light and shade? If it is a stern, it is yet a truthful, mirror. It flatters neither those who made it nor those blear-eyed maskers, who, forgetful of their own distorted visages, look in askance, and are able to see nothing to admire in the sober, bright-eyed faces of their fathers who gaze down upon them from the olden time.

The preamble of this constitution begins by reciting the fact that its authors are, “under Almighty God, inhabitants and residents of Windsor, Hartford, and Wethersfield, upon the river of Connecticut.” It also states that, in consonance with the word of God, in order to maintain the peace and union of such a people, it is necessary that “there should be an orderly and decent government established,” that shall “dispose of the affairs of the people at all seasons.” “We do therefore,” say they, “associate and conjoin ourselves to be as one public state or commonwealth.” They add, further, that the first object aimed at by them is to preserve the liberty and the purity of the gospel and the discipline of their own churches; and, in the second place, to govern their civil affairs by such rules as their written constitution and the laws enacted under its authority shall prescribe. To provide for these two objects–the liberty of the Gospel, as they understood it, and the regulation of their own civil affairs, they sought to embody in the form of distinct decrees, substantially the following provisions:

1. That there shall be every year two general assemblies or courts, one on the second Thursday of April, the other on the second Thursday of September; that the one held in April shall be called the court of election, wherein shall be annually chosen the magistrates–one of whom shall be the governor — and other public officers, who are to administer justice according to the laws here established; where there are no laws provided to do it in accordance with the laws of God; and that these rulers shall be elected by all the freemen within the limits of the commonwealth, who have been admitted inhabitants of the towns where they severally live, and who have taken the oath of fidelity to the new state; and that they shall all meet at one place to hold this election.

2. It is provided that after the voters have all met and are ready to proceed to an election, the first officer to be chosen shall be a governor, and after him a body of magistrates and other officers. Every voter is to bring in, to those who are appointed to receive it, a piece of paper with the name of him whom he would have for governor written upon it, and he that has the greatest number of papers with his name written upon them was to be governor for that year. The other magistrates were elected in the following manner. The names of all the candidates were first given to the secretary for the time being, and written down by him, in the order in which they were given; the secretary was then to read the list over aloud and severally nominate each person whose name was so written down, in its order, in a distinct voice, so that all the citizen voters could hear it. As each name was read, they were to vote by ballot, either for or against it, as they liked; those who voted in favor of the nominee did it by writing his name upon the ballot–those who voted against him simply gave in a blank ballot; and those only were elected whose names were written upon a majority of all the paper ballots handed in under each nomination. These papers were to be received and counted by sworn officers appointed by the court for that purpose. Six magistrates, besides the governor, were to be elected in this way. If they failed to elect so many by a majority vote, then the requisite number was to be filled up by taking the names of those who had received the highest number of votes.

3. The men thus to be nominated and balloted for were to be propounded at some general court held before the court of election, the deputies of each town having the privilege of nominating any two whom they chose. Other nominations might be made by the court.

4. No person could be chosen governor oftener than once in two years. It was requisite that this officer should be a member of an approved congregation, and that he should be taken from the magistrates of the commonwealth. But no qualification was required in a candidate for the magistracy, except that he should be chosen from the freemen. Both governor and magistrates were required to take a solemn oath of office.

| Master List | Next—> |

John Marshall begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.