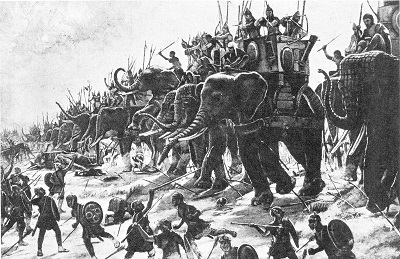

Hannibal, in order to terrify the enemy, drew up his elephants in front, and he had eighty of them, being more than he had ever had in any battle.

Continuing Scipio Africanus Crushes Hannibal at Zama and Subjugates Carthage,

our selection from History of Rome, Book XII by Livy published in between 27 BC and 9 BC. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Scipio Africanus Crushes Hannibal at Zama and Subjugates Carthage.

Time: 202 BC

Place: Zama, Tunisia

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Thus, without effecting an accommodation, when they had returned from the conference to their armies, they informed them that words had been bandied to no purpose, that the question must be decided by arms, and that they must accept that fortune which the gods assigned them.

When they had arrived at their camps, they both issued orders that their soldiers should get their arms in readiness and prepare their minds for the final contest; in which, if fortune should favor them, they would continue victorious, not for a single day, but forever. “Before to-morrow night,” they said, “they would know whether Rome or Carthage should give laws to the world, and that neither Africa nor Italy, but the whole world, would be the prize of victory. That the dangers which threatened those who had the misfortune to be defeated were proportioned to the rewards of the victors.” For the Romans had not any place of refuge in an unknown and foreign land, and immediate destruction seemed to await Carthage if the troops which formed her last reliance were defeated. To this important contest, the day following, two generals, by far the most renowned of any, and belonging to two of the most powerful nations in the world, advanced either to crown or overthrow on that day the many honors they had previously acquired.

Scipio drew up his troops, posting the hastati in front, the principes behind them, and closing his rear line with the triarii. He did not draw up his cohorts in close order, but each before their respective standards; placing the companies at some distance from each other, so as to leave a space through which the elephants of the enemy passing might not at all break their ranks. Laelius, whom he had employed before as lieutenant-general, but this year as quaestor, by special appointment, according to a decree of the senate, he posted with the Italian cavalry in the left wing, Masinissa and the Numidians in the right. The open spaces between the companies of those in the van he filled with velites, which then formed the Roman light-armed troops, with an injunction that on the charge of the elephants they should either retire behind the files, which extended in a right line, or, running to the right and left and placing themselves by the side of those in the van, afford a passage by which the elephants might rush in between weapons on both sides.

Hannibal, in order to terrify the enemy, drew up his elephants in front, and he had eighty of them, being more than he had ever had in any battle; behind these his Ligurian and Gallic auxiliaries, with Balearians and Moors intermixed. In the second line he placed the Carthaginians, Africans, and a legion of Macedonians; then, leaving a moderate interval, he formed a reserve of Italian troops, consisting principally of Bruttians, more of whom had followed him on his departure from Italy by compulsion and necessity than by choice. His cavalry also he placed in the wings, the Carthaginian occupying the right, the Numidian the left. Various were the means of exhortation employed in an army consisting of a mixture of so many different kinds of men; men differing in language, customs, laws, arms, dress, and appearance, and in the motives for serving. To the auxiliaries, the prospect both of their present pay and many times more from the spoils was held out. The Gauls were stimulated by their peculiar and inherent animosity against the Romans. To the Ligurians the hope was held out of enjoying the fertile plains of Italy, and quitting their rugged mountains, if victorious. The Moors and Numidians were terrified with subjection to the government of Masinissa, which he would exercise with despotic severity.

Different grounds of hope and fear were represented to different persons. The view of the Carthaginians was directed to the walls of their city, their household gods, the sepulchres of their ancestors, their children and parents, and their trembling wives; they were told that either the destruction of their city and slavery or the empire of the world awaited them; that there was nothing intermediate which they could hope for or fear.

While the general was thus busily employed among the Carthaginians, and the captains of the respective nations among their countrymen, most of them employing interpreters among troops intermixed with those of different nations, the trumpets and cornets of the Romans sounded; and such a clamor arose that the elephants, especially those in the left wing, turned round upon their own party, the Moors and Numidians. Masinissa had no difficulty in increasing the alarm of the terrified enemy, and deprived them of the aid of their cavalry in that wing. A few, however, of the beasts which were driven against the enemy, and were not turned back through fear, made great havoc among the ranks of the velites, though not without receiving many wounds themselves; for when the velites, retiring to the companies, had made way for the elephants, that they might not be trampled down, they discharged their darts at them; exposed as they were to wounds on both sides, those in the van also keeping up a continual discharge of javelins, until driven out of the Roman line by the weapons which fell upon them from all quarters, these elephants also put to flight even the cavalry of the Carthaginians posted in their right wing. Laelius, when he saw the enemy in disorder, struck additional terror into them in their confusion.

The Carthaginian line was deprived of the cavalry on both sides, when the infantry, who were now not a match for the Romans in confidence or strength, engaged. In addition to this there was one circumstance, trifling in itself, but at the same time producing important consequences in the action. On the part of the Romans the shout was uniform, and on that account louder and more terrific, while the voices of the enemy, consisting as they did of many nations of different languages, were dissonant. The Romans used the stationary kind of fight, pressing upon the enemy with their own weight and that of their arms; but on the other side there was more of skirmishing and rapid movement than force. Accordingly, on the first charge, the Romans immediately drove back the line of their opponents; then pushing them with their elbows and the bosses of their shields, and pressing forward into the places from which they had pushed them, they advanced a considerable space, as though there had been no one to resist them, those who formed the rear urging forward those in front when they perceived the line of the enemy giving way, which circumstance itself gave great additional force in repelling them.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.