As Russia entered the nineteenth century, the hearts of earnest men must have sunk within them.

Continuing Russian Serfs Freed,

with a selection from The Development and Overthrow of the Russian Serf System in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, Volume X by Andrew D. White published in 1862. This selection is presented in 8 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Russian Serfs Freed.

Time: 1861

Place: Russia

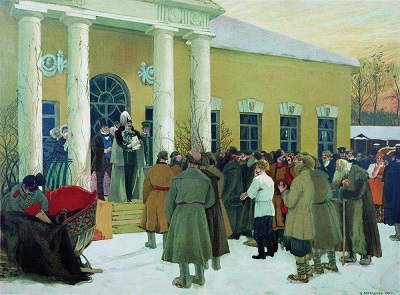

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

For Peter saw other nations spinning and weaving, and he determined that Russia should at once spin and weave; he saw other nations forging iron, and he determined that Russia should at once forge iron. He never stopped to consider that what might cost little in other lands as a natural growth, might cost far too much in Russia as a forced growth. In lack, then, of quick brain and sturdy spine and strong arm of paid workmen, he forced into his manufactories the flaccid muscle of serfs. These, thus lifted from the earth, lost even the little force in the State they had before; great bodies of serfs thus became slaves; worse than that, the idea of a serf developed toward the idea of a slave.

And Peter, misguided, dealt one blow more. Cold-blooded officials were set at taking the census. These adopted easy classifications; free peasants, serfs, and slaves were often huddled into the lists under a single denomination. So serfage became still more difficult to be distinguished from slavery. As this base of hideous wrong was thus widened and deepened the nobles built higher and stronger their superstructure of arrogance and pretension. Not many years after Peter’s death, they so overawed the Empress Anne that she thrust into the codes of the empire statutes which allowed the nobles to sell serfs apart from the soil. So did serfage bloom fully into slavery.

But in the latter half of the eighteenth century Russia gained a ruler from whom the world came to expect much. To mount the throne, Catharine II had murdered her husband; to keep the throne she had murdered two claimants whose title was better than her own. She then became, with her agents in these horrors, a second Messalina. To set herself right in the eyes of Europe, she paid eager court to that hierarchy of scepticism which in that age made or marred European reputations. She flattered the fierce deists by owning fealty to “Le Roi” Voltaire; she flattered the mild deists by calling in La Harpe as the tutor of her grandson; she flattered the atheists by calling in Diderot as a tutor for herself.

Her murders and orgies were soon forgotten in the new hopes for Russian regeneration. Her dealings with Russia strengthened these hopes. The official style required that all persons presenting petitions should subscribe themselves “Your Majesty’s humble serf.” This formula she abolished, and boasted that she had cast out the word serf from the Russian language. Poets and philosophers echoed this boast over Europe — and the serfs waited.

The great Empress spurred hope by another movement. She proposed to an academy the question of serf emancipation as a subject for their prize essay. The essay was written and crowned. It was filled with beautiful things about liberty, practical things about moderation, flattering things about the “Great Catharine” — and the serfs waited.

Again she aroused hope. It was given out that her most intense delight came from the sight of happy serfs and prosperous villages. Accordingly, in her journey to the Crimea, Potemkin squandered millions on millions in rearing pasteboard villages, in dragging forth thousands of wretched peasants to fill them, in costuming them to look thrifty, in training them to look happy. Catharine was rejoiced, Europe sang paeans — the serfs waited.

She seemed to go further: she issued a decree prohibiting the enslavement of serfs. But unfortunately the palace intrigues, and the correspondence with the philosophers, and the destruction of Polish nationality left her no time to see the edict carried out. But Europe applauded — and the serfs waited. Two years after this came a deed which put an end to all this uncertainty. An edict was prepared ordering the peasants of Little Russia to remain forever on the estates where the day of publication should find them. This was vile; but what followed was diabolic. Court pets were let into the secret. These, by good promises, enticed hosts of peasants to their estates. The edict was now sprung; in an hour the courtiers were made rich, the peasants were made serfs, and Catharine II was made infamous forever. So, about a century after Peter, a wave of wrong rolled over Russia that not only drowned honor in the nobility, but drowned hope in the people.

As Russia entered the nineteenth century, the hearts of earnest men must have sunk within them. For Paul I, Catharine’s son and successor, was infinitely more despotic than Catharine, and infinitely less restrained by public opinion. He had been born with savage instincts, and educated into ferocity. Tyranny was written on his features in his childhood. If he remained in Russia his mother sneered and showed hatred of him; if he journeyed in Western Europe crowds gathered about his coach to jeer at his ugliness. Most of those who have seen Gillray’s caricature of him, issued in the height of English spite at Paul’s homage to Bonaparte, have thought it hideously overdrawn; but those who have seen the portrait of Paul in the Cadet-Corps of St. Petersburg know well that Gillray did not exaggerate Paul’s ugliness, for he could not.

And Paul’s face was but a mirror of his character. Tyranny was wrought into his every fibre. He demanded an oriental homage. As his carriage whirled by, it was held the duty of all others in carriages to stop, descend into the mud, and bow themselves. Himself threw his despotism into this formula: “Know, Sir Ambassador, that in Russia there is no one noble or powerful except the man to whom I speak, and while I speak.”

And yet within that hideous mass glowed sparks of reverence for right. When the nobles tried to get Paul’s assent to more open arrangements for selling serfs apart from the soil, he utterly refused; and when they overtasked their human chattels Paul made a law that no serf should be required to give more than three days in the week to the tillage of his master’s domain. But, within five years after his accession, Paul had developed into such a ravenous wild beast that it became necessary to murder him. This duty done, there came a change in the spirit of Russian sovereignty as from March to May; but, sadly for humanity, there came at the same time a change in the spirit of European politics, as from May to March.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Andrew D. White begins here. Nikolai Turgenieff begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.