Straightway an answer was sent conveying the outlines of the Emperor’s plan. The period of transition from serfage to freedom was set at twelve years.

Continuing Russian Serfs Freed,

with a selection from The Development and Overthrow of the Russian Serf System in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, Volume X by Andrew D. White published in 1862. This selection is presented in 8 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Russian Serfs Freed.

Time: 1861

Place: Russia

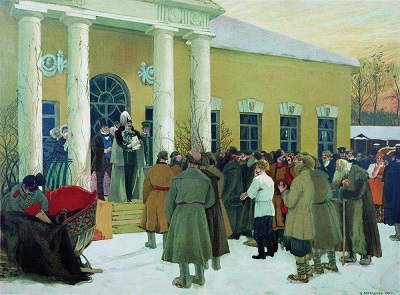

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

They had curiosity, which under a better system would have made them inventive; but their plough, in common use, was behind the plough described by Vergil. They had a love of gain, which under a better system would have made them hardworking; but it took ten serfs to do, languidly and poorly, what two free men in America would do quickly and well. They were naturally a kind people; but let one example show how serfage can transmute kindness. It is a rule, well known in Russia, that when an accident occurs, interference is to be left to the police. Hence you would see a man lying in a fit, and the bystanders giving no aid, but waiting for the authorities. Some years ago, as all the world remembers, a theatre took fire in St. Petersburg, and crowds of people were burned or stifled. The whole story is not so well known. The theatre was but a great temporary wooden shed — such as is run up every year at the holidays, in the public squares. When the fire burst forth, crowds of peasants hurried to the spot; but though they heard the shrieks of the dying, separated from them only by a thin planking, only one man in that multitude dared cut through and rescue some of the sufferers.

The serfs, when standing for great ideas, would die rather than yield. Napoleon I learned this at Eylau; Napoleon III learned it at Sebastopol; yet in daily life they were slavish beyond belief. On a certain day, in the year 1855, the most embarrassed man in all Russia was doubtless our excellent American minister. The serf coachman employed at wages was called up to receive his discharge for drunkenness. Coming into the presence of a sound-hearted American democrat, who never had dreamed of one mortal kneeling to another, Ivan throws himself on his knees, presses his forehead to the minister’s feet, fawns like a tamed beast, and refuses to move until the minister relieves himself from this nightmare of servility by a full pardon.

Time after time we have entered the serf field and serf hut; have seen the simple round of serf toils and sports; have heard the simple chronicles of self joys and sorrows: but whether his livery were filthy sheepskin or gold-laced caftan; whether he lay on carpets at the door of his master, or in filth on the floor of his cabin; whether he gave us cold, stupid stories of his wrongs, or flippant details of his joys; whether he blessed his master or cursed him — we have wondered at the power which a serf system has to degrade and imbrute the image of God.

But astonishment was increased a thousand-fold at study of the reflex influence for evil upon the serf-owners themselves, upon the whole free community, upon the very soil of the whole country. On all those broad plains of Russia, on the daily life of that serf-owning aristocracy, on the whole class which was neither of serfs nor serf-owners, the curse of God was written in letters so big and so black that all mankind might read them. Farms were untilled, enterprise deadened, invention crippled, education neglected; life was of little value; labor was the badge of servility, laziness the very badge and passport of gentility. Despite the most specious half-measures, despite all efforts to galvanize it, to coax life into it, to sting life into it, the nation remained stagnant. Not one traveler who does not know that the evils brought on that land by the despotism of the autocrat were as nothing compared to that dark network of curses spread over it by a serf-owning aristocracy. Into the conflict with this evil Alexander II entered manfully. Having been two years upon the throne, having made a plan, having stirred some thought through certain authorized journals, he inspired the nobility in three of the northwestern provinces to memorialize him in regard to emancipation.

Straightway an answer was sent conveying the outlines of the Emperor’s plan. The period of transition from serfage to freedom was set at twelve years; at the end of that time the serf was to be fully free and possessor of his cabin, with an adjoining piece of land. The provincial nobles were convoked to fill out these outlines with details as to the working out by the serfs of a fair indemnity to their masters. The whole world was stirred; but that province in which the Czar hoped most eagerly for a movement to meet him — the province where beat the old Muscovite heart, Moscow — was stirred least of all. Every earnest throb seemed stifled there by that strong aristocracy.

Yet Moscow moved at last. Some nobles who had not yet arrived at the callous period; some professors in the University who had not yet arrived at the heavy period, breathed life into the mass, dragged on the timid, fought off the malignant. The movement had soon a force which the retrograde party at Moscow dared not openly resist. So they sent answers to St. Petersburg, apparently favorable; but wrapped in their phrases were hints of difficulties, reservations, impossibilities. All this studied suggestion of difficulties profited the reactionists nothing. They were immediately informed that the imperial mind was made up, that the business of the Muscovite nobility was now to arrange that the serf be freed in twelve years, and put in possession of homestead and enclosure.

The next movement of the retrograde party was to misunderstand everything. The plainest things were found to need a world of debate; the simplest things became entangled; the noble assemblies played solemnly a ludicrous game of cross-purposes. Straightway came a notice from the Emperor which, stripped of official verbiage, said that they must understand. This set all in motion again. Imperial notices were sent to province after province, explanatory documents were issued, good men and strong were set to talk and work.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Andrew D. White begins here. Nikolai Turgenieff begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.