He had struggled long to make some satisfactory previous arrangement; his motto now became: Emancipation first, arrangement afterward.

Continuing Russian Serfs Freed,

with a selection from The Development and Overthrow of the Russian Serf System in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, Volume X by Andrew D. White published in 1862. This selection is presented in 8 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Russian Serfs Freed.

Time: March 5, 1861

Place: Russia

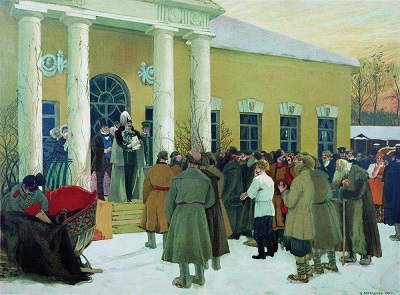

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The nobility of Moscow made another move. To scare back the advancing forces of emancipation, they elected, as provincial leaders, three nobles bearing the greatest names of old Russia and haters of the new ideas. To defeat these came a successor of St. Gregory and St. Bavon, one who accepted the thought that when God advances great ideas the Church must marshal them. Philarete, Metropolitan of Moscow, upheld emancipation and condemned its foes; his earnest eloquence carried all. The work progressed unevenly — nobles in different governments differed in plan and aim — an assembly of delegates was brought together at St. Petersburg to combine and perfect a resultant plan under the eye of the Emperor. The Grand Council of the Empire, too, was set at the work. It was a most unpromising body, yet the Emperor’s will stirred it.

The opposition now made the most brilliant stroke of its campaign. Just as James II of England prated of toleration and planned the enslavement of all thought, so now the bigoted plotters against emancipation began to prate of constitutional liberty. But Alexander held right on. It was even hinted that visions of a constitutional monarchy pleased him. But then came tests of Alexander’s strength far more trying. Masses of peasants, hearing vague news of emancipation — learning, doubtless, from their masters’ own spiteful lips that the Emperor was endeavoring to tear away property in serfs — took the masters at their word, and determined to help the Emperor. They rose in insurrection. To the bigoted serf-owners this was a godsend. They paraded it in all lights; therewith they threw life into all the old commonplaces on the French Revolution; timid men of good intentions wavered. The Czar would surely now be scared back.

Not so. Alexander now hurled his greatest weapon, and stunned reaction in a moment. He freed all the serfs on the Imperial estates without reserve. Now it was seen that he was in earnest; the opponents were disheartened; once more the plan moved and dragged them on. But there came other things to dishearten the Emperor; and not least of these was the attitude of those who moulded popular thought in England. Be it said here, to the credit of France, that from her came constant encouragement in the great work. Wolowski, Mazade, and other true-hearted men sent forth from leading reviews and journals words of sympathy, words of help, words of cheer.

Not so England. Just as in the French Revolution of 1789, while yet that Revolution was noble and good, while yet Lafayette and Bailly held it, leaders in English thought, who had quickened the opinions which had caused the Revolution, sent malignant prophecies and prompted foul blows, so in this battle of Alexander against a foul wrong they seized this time of all times to show all the wrongs and absurdities of which Russia ever had been or ever might be guilty — criticised, carped, sent much haughty advice, depressing sympathy, and malignant prophecy. Review articles, based on no real knowledge of Russia, announced a desire for serf-emancipation, and then, in the modern English way, with plentiful pyrotechnics of antithesis and paradox, threw a gloomy light into the skilfully pictured depths of imperial despotism, official corruption, and national bankruptcy.

They revived Old World objections, which, to one acquainted with the most every-day workings of serfage, were ridiculous. It was said that if the serfs lost the protection of their owners they might fall a prey to rapacious officials. As well might it have been argued that a mother should never loose her son from her apron-strings. It was said that “Serfism excludes pauperism” — that, if the serf owes work to his owner in the prime of life, the owner owes support to his serf in the decline of life. No lie could be more absurd to one who had seen Russian life. We were first greeted, on entering Russia, by a beggar who knelt in the mud; at Kovno eighteen beggars besieged the coach, and Kovno was hardly worse than scores of other towns; within a day’s ride from St. Petersburg a woman begged piteously for means to keep soul and body together, and finished the refutation of that sonorous English theory, for she had been discharged from her master’s service in the metropolis as too feeble, and had been sent back to his domain, afar in the country, on foot and without money.

It was said that freed peasants would not work. But, despite volleys of predictions that they would not work if freed, despite volleys of assertions that they could not work if freed, the peasants when set free, and not crushed by regulations, have sprung to their work with an earnestness and continued it with a vigor at which the philosophers of the old system stand aghast. The freed peasants of Wologda compare favorably with any in Europe. And when the old tirades had grown stale, English writers drew copiously from a new source — from La Vérité sur la Russie — pleasingly indifferent to the fact that the author’s praise in a previous work had notoriously been a thing of bargain and sale, and that there was in full process of development a train of facts which led the Parisian courts to find him guilty of demanding in one case a blackmail of fifty thousand rubles.

All this argument outside the empire helped the foes of emancipation inside the empire. But the Emperor met the whole body of his opponents with an argument overwhelming. On March 5, 1861, he issued his manifesto making the serfs free! He had struggled long to make some satisfactory previous arrangement; his motto now became: Emancipation first, arrangement afterward. Thus was the result of the great struggle decided.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Andrew D. White begins here. Nikolai Turgenieff begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.