In consequence of the Alien and Sedition laws, Jefferson began to see the question in a different light.

Continuing Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists,

with a selection from Constitutional and Political History of the United States by Hermann Von Holst published in 1891. This selection is presented in 6.5 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists.

Time: 1798

Place: Washington, D.C.

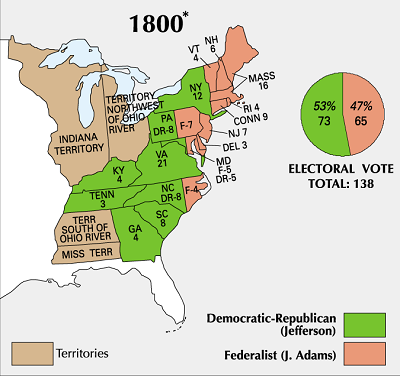

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Lloyd’s bill did not come up to be voted upon in its original form; but the Alien and Sedition laws were of themselves sufficient to realize Hamilton’s fears. The supremacy of Massachusetts and Connecticut had become so unbearable to the South that the idea of separation arose again in May. The influential John Taylor of Virginia thought “that it was not unwise now to estimate the separate mass of Virginia and North Carolina with a view to their separate existence.” Jefferson wrote him in relation to this advice, on June 1, 1798, “that it would not be wise to proceed immediately to a disruption of the Union when party passion was at such a height. If we now reduce our Union to Virginia and North Carolina, immediately the conflict will be established between those two States, and they will end by breaking into their simple units.”

As it was necessary that there should be some party to oppose, it was best to keep the New England States for this purpose. He had nothing to say against the rightfulness of the step. He con tented himself with dissuading from it on grounds of expediency. He counselled patience until fortune should change, and the “lost principles” might be regained, “for this is a game in which principles are the stake.”

Considering these views, it is not to be wondered at that, in consequence of the Alien and Sedition laws, Jefferson began to see the question in a different light. We shall have something to say later on the question whether, and to what extent, he considered it timely to discuss the secession of Virginia from the Union. But he was soon satisfied that his opponents had bent the bow too nearly to the point of breaking, to permit him to look upon further patient waiting for better fortune as the right policy. It was no longer time to stop at the exchange of private opinion and the declarations of individuals. The moment had now come when the “principles” should be distinctly formulated and officially proclaimed and recognized. Not to do this would be to run the risk of being carried away by the current of facts to such a distance that it would be difficult and perhaps impossible to get hold of the principles again. But if, on the other hand, this were done, everything further might be calmly waited for, and the policy of expediency again brought into the foreground. The protest was officially recorded; and so long as it was not, either willingly or under completion, as officially recalled, or at least withdrawn, it was to be considered as part of the record which might be taken advantage of at any stage of the case. Herein lies the immense significance of the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions.

Their importance is enhanced by the fact that Madison, who had merited well of the country, on account of his share in the drawing up and adoption of the Constitution, and whose exposition of it is therefore of the greatest weight, was the author of the Virginia resolution of December 24, 1798, and by the further fact that Jefferson, the oracle of the Anti-Federalists, had written the original draft of the Kentucky resolutions of November 10, 1798.

Although not in accord with chronological order, it is advisable to consider the Virginia resolutions first, for the reason that they do not go as far as the Kentucky resolutions. According to the testimony of their authors, the resolutions of both Legislatures had the same source, and there were special reasons why it was necessary to make the Virginia resolutions of a milder character. Although a violation of chronological order, it seems, therefore, proper to consider these as the basis of the Kentucky resolutions, or rather as a lower round of the same ladder.

The paragraph of the Virginia resolutions of most importance for the history of the Constitution is the following:

Resolved, That this Assembly doth emphatically and peremptorily declare that it views the powers of the Federal Government as resulting from the compact to which the States are parties as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact, as no further valid than they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the States who are parties thereto have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil and for maintaining within their respective limits the authorities, rights, and liberties appertaining to them.”

The Legislature of Kentucky disdained to use a mode of expression so vague and feeble or to employ language from which much or little might be gathered as occasion demanded. In the first paragraph of the resolutions of November 10, 1798, we read:

Resolved, That whenever the General Government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force; that to this compact each State acceded as a State, and is an integral party; that this Government, created by this compact, was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself, since that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers; but that, as in all other cases of compact among parties having no common judge, each party has an equal right to judge for itself as well of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress.”

Thus were the “principles” established. But in order that they might not remain a thing floating in the air it was necessary to provide another formula, by which the States might be empowered to enforce the rights claimed, or at least to find a word which would presumably embody that formula, and which was sufficient so long as they limited themselves to the theoretical discussion of the question. The Legislature of Kentucky, in its resolutions of November 14, 1799, gave the advocates of State rights the term demanded, in the sentence:

Resolved, That the several States who formed that instrument being sovereign and independent, have the unquestionable right to judge of the infraction; and that a nullification by these sovereignties, of all unauthorized acts done under color of that instrument, is the rightful remedy.”

–

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Hermann Von Holst begins here. Thomas Jefferson begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.