The Emperor, however, on his return home, soon discovered that his pilgrimage to the West had been lost labor.

Continuing Orthodox, Catholics Split,

with a selection from The Church and the Eastern Empire by Henry F. Tozer published in 1888. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long.

Previously in Orthodox, Catholics Split.

Time: 1054

Place: Rome and Constantinople

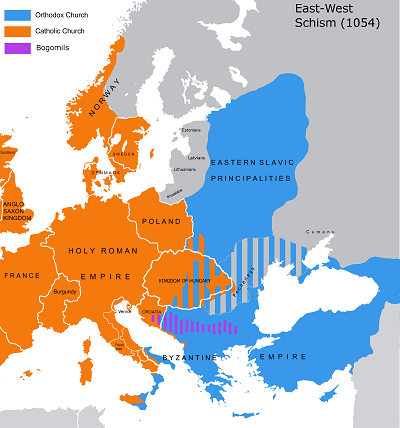

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Directions were further given for circulating this missive among the Western clergy. It happened that at the time when the letter arrived at Trani, Cardinal Humbert, a vigorous champion of ecclesiastical rights, was residing in that city, and he translated it into Latin and communicated it to Pope Leo IX. In answer, the Pope addressed a remonstrance to the Patriarch, in which, without entering into the specific charges that he had brought forward, he contrasted the security of the Roman See in matters of doctrine, arising from the guidance which was guaranteed to it through St. Peter, with the liability of the Eastern Church to fall into error, and pointedly referred to the more Christian spirit manifested by his own communion in tolerating those from whose opinions they differed. Afterward, at the commencement of 1054, in compliance with a request from the emperor Constantine Monomachus, who was anxious on political grounds to avoid a rupture, he sent three legates to Constantinople to arrange the terms of an agreement. These were Frederick of Lorraine, Chancellor of the Roman Church; Peter, Archbishop of Amalfi, and Cardinal Humbert.

The legates were welcomed by the Emperor, but they unwisely adopted a lofty tone toward the haughty Patriarch, who thenceforward avoided all communication with them, declaring that on a matter which so seriously affected the whole Eastern Church he could take no steps without consulting the other patriarchs. Humbert now published an argumentative reply to Michael’s letter to the Pope, in the form of a dialogue between two members of the Greek and Latin churches, in which the charges brought against his own communion were discussed seriatim, and especially those relating to fasting on Saturday and the use of unleavened bread in the eucharist. A rejoinder to this appeared from the pen of a monk of the monastery of Studium, Nicetas Pectoratus, in which the enforced celibacy of the Western clergy, on which Photius had before animadverted, was severely criticised. The Cardinal retorted in intemperate language, and so entirely had the legates secured the support of Constantine that Nicetas’ work was committed to the flames, and he was forced to recant what he had said against the Roman Church. But the Patriarch was immovable, and for the moment he occupied a stronger position than the Emperor, who desired to conciliate him. At last the patience of the legates was exhausted, and on July 16, 1054, they proceeded to the Church of St. Sophia, and deposited on the altar, which was prepared for the celebration of the eucharist, a document containing a fierce anathema, by which Michael Cerularius and his adherents were condemned. After their departure they were for a moment recalled, because the Patriarch expressed a desire to confer with them; but this Constantine would not permit, fearing some act of violence on the part of the people. They then finally left Constantinople, and from that time to the present all communion has been broken off between the two great branches of Christendom.

The breach thus made was greatly widened at the period of the crusades. However serious may have been the alienation between the East and West at the time of their separation, it is clear that the Greeks were not regarded by the Latins as a mere heretical sect, for one of the primary objects with which the First Crusade was undertaken was the deliverance of the Eastern Empire from the attacks of the Mahometans. But the familiarity which arose from the presence of the crusaders on Greek soil ripened the seeds of mutual dislike and distrust. As long as negotiations between the two parties took place at a distance, the differences, however irreconcilable they might be in principle, did not necessarily bring them into open antagonism, whereas their more intimate acquaintance with one another produced personal and national ill-will. The people of the West now appeared more than ever barbarous and overbearing, and the Court of Constantinople more than ever senile and designing. The crafty policy of Alexius Comnenus in transferring his allies with all speed into Asia, and declining to take the lead in the expedition, was almost justified by the necessity of delivering his subjects from these unwelcome visitors and avoiding further embarrassments. But the iniquitous Fourth Crusade (1204) produced an ineradicable feeling of animosity in the minds of the Byzantine people. The memory of the barbarities of that time, when many Greeks died as martyrs at the stake for their religious convictions, survives at the present day in various places bordering on the Aegean, in legends which relate that they were formerly destroyed by the Pope of Rome.

Still, the anxiety of the Eastern emperors to maintain their position by means of political support from Western Europe brought it to pass that proposals for reunion were made on several occasions. The final attempt at reconciliation was made when the Greek empire was reduced to the direst straits, and its rulers were prepared to purchase the aid of Western Europe against the Ottomans by almost any sacrifice. Accordingly, application was made to Pope Eugenius IV, and by him the representatives of the Eastern Church were invited to attend the council which was summoned to meet at Ferrara in 1438. The Emperor, John Palaeologus and the Greek patriarch Joseph proceeded thither.

The Emperor, however, on his return home, soon discovered that his pilgrimage to the West had been lost labor. Pope Eugenius, indeed, provided him with two galleys and a guard of three hundred men, equipped at his own expense, but the hoped-for succors from Western Europe did not arrive. His own subjects were completely alienated by the betrayal of their cherished faith; the clergy who favored the union were regarded as traitors. John Palaeologus himself did not survive to see the final catastrophe; but Constantinople was captured by the Turks, and the Empire of the East ceased to exist.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Henry F. Tozer begins here. Joseph Deharbe begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.