Already in the papacy of Nicholas I a rupture had occurred in connection with the dispute between the rival patriarchs of Constantinople, Ignatius and Photius.

Continuing Orthodox, Catholics Split,

with a selection from The Church and the Eastern Empire by Henry F. Tozer published in 1888. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long.

Previously in Orthodox, Catholics Split.

Time: 1054

Place: Rome and Constantinople

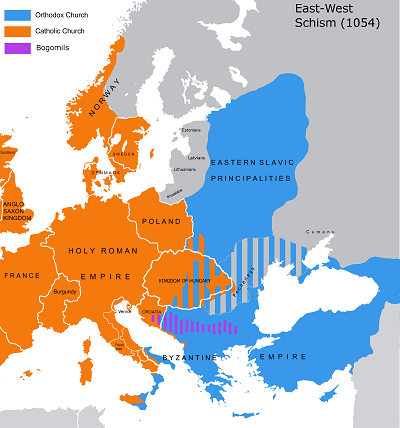

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But the great advance was made in the pontificate of Nicholas I (858-867), who promulgated, or at least recognized, the False Decretals. This famous compilation, which is now universally acknowledged to be spurious, and can be shown to be the work of that period, contains, among other documents, letters and decrees of the early bishops of Rome, in which the organization and discipline of the Church from the earliest time are set forth, and the whole system is shown to have depended on the supremacy of the popes. The newly discovered collection was recognized as genuine by Nicholas, and was accepted by the Western Church. The effect of this was at once to formulate all the claims which had before been vaguely asserted, and to give them the authority of unbroken tradition. The result to Christendom at large was in the highest degree momentous. It was impossible for future popes to recede from them, and equally impossible for other churches which valued their independence to acknowledge them. The last attempt on the part of the Eastern Church to arrange a compromise in this matter was made by the emperor Basil II, a potentate who both by his conquests and the vigor of his administration might rightly claim to negotiate with others on equal terms. By him it was proposed (A.D. 1024) that the Eastern Church should recognize the honorary primacy of the Western patriarch, and that he in turn should acknowledge the internal independence of the Eastern Church. These terms were rejected, and from that moment it was clear that the separation of the two branches of Christendom was only a question of time.

Already in the papacy of Nicholas I a rupture had occurred in connection with the dispute between the rival patriarchs of Constantinople, Ignatius and Photius. The former of these prelates, who was son of the emperor Michael I, and a man of high character and a devout opponent of iconoclasm, was appointed, through the influence of Theodora, the restorer of images, in the reign of her son, Michael the Drunkard. But the uncle of the Emperor, the Caesar Bardas, who was a man of flagrantly immoral life, had divorced his own wife, and was living publicly with his son’s widow. For this incestuous connection Ignatius repelled him from the communion. Fired with indignation at this insult, the Caesar determined to ruin both the Patriarch and his patroness, the Empress-mother, and with this view persuaded the Emperor to free himself from the trammels of his mother’s influence by forcing her to take monastic vows. To this step Ignatius would not consent, because it was forbidden by the laws of the Church that any should enter on the monastic life except of their own free will. In consequence of his resistance a charge of treasonable correspondence was invented against him, and when he refused to resign his office he was deposed (857). Photius, who was chosen to succeed him, was the most learned man of his age, and like his rival, unblemished in character and a supporter of images, but boundless in ambition. He was a layman at the time of his appointment, but in six days he passed through the inferior orders which led up to the patriarchate. Still, the party that remained faithful to Ignatius numbered many adherents, and therefore Photius thought it well to enlist the support of the Bishop of Rome on his side. An embassy was therefore sent to inform Pope Nicholas that the late Patriarch had voluntarily retired, and that Photius had been lawfully chosen, and had undertaken the office with great reluctance. In answer to this appeal the Pope dispatched two legates to Constantinople, and Ignatius was summoned to appear before a council at which they were present. He was condemned, but appealed to the Pope in person.

On the return of the legates to Rome it was discovered that they had received bribes, and thereupon Nicholas, whose judgment, however imperious, was ever on the side of the oppressed, called together a synod of the Roman Church, and refused his consent to the deposition of Ignatius. To this effect he wrote to the authorities of the Eastern Church, calling upon them at the same time to concur in the decrees of the apostolic see; but subsequently, having obtained full information as to the harsh treatment to which the deposed Patriarch had been subjected, he excommunicated Photius, and commanded the restoration of Ignatius “by the power committed to him by Christ through St. Peter.”

These denunciations produced no effect on the Emperor and the new Patriarch, and a correspondence between Michael and Nicholas, couched in violent language, continued at intervals for several years. At last, in consequence of a renewed demand on the part of the Pope that Ignatius and Photius should be sent to Rome for judgment, the latter prelate, whose ability and eloquence had obtained great influence for him, summoned a council at Constantinople in the year 867, to decree the counter-excommunication of the Western Patriarch. Of the eight articles which were drawn up on this occasion for the incrimination of the Church of Rome, all but two relate to trivial matters, such as the observance of Saturday as a fast, and the shaving of their beards by the clergy. The two important ones deal with the doctrine of the Procession of the Holy Spirit, and the enforced celibacy of the clergy.

The condemnation of the Western Church on these grounds was voted, and a messenger was dispatched to bear the defiance to Rome; but ere he reached his destination he was recalled, in consequence of a revolution in the palace at Constantinople. The author of this, Basil the Macedonian, the founder of the most important dynasty that ever occupied the throne of the Eastern Empire, had for some time been associated in the government with the emperor Michael; but at length, being fearful for his own safety, he resolved to put his colleague out of the way, and assassinated him during one of his fits of drunkenness.

It is said that in consequence of this crime Photius refused to admit him to the communion; anyhow, one of the first acts of Basil was to depose Photius. A council, hostile to him, was now assembled, and was attended by the legates of the new pope, Hadrian II (869). By this Ignatius was restored to his former dignity, while Photius was degraded and his ordinations were declared void. So violent was the animosity displayed against him that he was dragged before the assembly by the Emperor’s guard, and his condemnation was written in the sacramental wine. During the ten years which elapsed between his restoration and his death Ignatius continued to enjoy his high position in peace, but for Photius other vicissitudes were in store.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Henry F. Tozer begins here. Joseph Deharbe begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.